Entries Tagged 'software' ↓

February 5th, 2009 — baltimore, business, design, economics, philosophy, social media, software

The First Church of American Business teaches that virtue accrues from execution, and that the ability to manage big, complex to-do lists either personally or via delegation is the key to getting ahead in business.

From there it also holds that competition is all about having and managing longer and more complex to-do lists, and beating out the other guy who’s presumably doing the same thing. Books with titles like “Execution,” “Getting Things Done,” and the “7 Habits of Highly Effective People” depict the business world as a crazy-making self-perpetuating scheme of testosterone-fueled competition, which ultimately aims to canonize its Saints the way the sports world does its highest trophy winners.

Business book writers have it particularly easy; they go back and look for the “winners” of this apparent competition (Jack Welch, Bill Gates, Eric Schmidt) and assign them all manner of superhuman qualities. Occasionally they come across somebody who somehow managed to get on top without shaming (and presumably out-executing) all of his or her peers, and they shrug in disbelief and assume that they must have “the vision thing” and canonize the schmuck anyway; the last thing the high priests of productivity would want to admit was that they didn’t see someone coming.

My deepest wish is to go back to 1960 or 1985 (maybe both) and gouge out the eyes of these practitioners with their own tassel loafers. We’ve seen how this all worked out; this approach to business has led us to the only place it could: a testosterone-fueled sham of an economy.

Certainly execution is important. But in the rush to assign virtue to execution itself, we’ve lost sight of what it is we’re executing – that “vision thing.”

Design is the most important force for good in the world today. Overstated? I don’t think so. Design indicates intent. I believe humanity has good intentions for the world; therefore I believe that design is the way in which we will manifest those good intentions.

Many people are confused about what design is. They confuse it with industrial design (iPod, Beetle, Aeron Chairs) or graphic design (packaging, advertising, marketing, websites), or simply assume it’s one of those “art things” that they don’t have to worry about because they didn’t study it in business school.

But in fact, people design things every day. We are all designers of our lives. In the simplest choices, we are signaling our intentions about how we want to interact with the world and sending subtle cues about the kinds of interactions we desire.

Getting good at design is a little bit like becoming a Jedi master – it comes from a place inside where less is more and where silence is more powerful than sound. It’s about looking for the reasons why something will work rather than the ways it might fail. It’s about finding the line, the melody, the art, the poetry in mundane transactional details and teasing it out to make it serve you. It’s tough to explain, but over the next few days, I’ll be reviewing some recent, unconventional examples of design in my own experience.

Design is all about executing a small number of the right tasks.

December 16th, 2008 — art, business, design, economics, social media, software, trends, visualization

Last week I had the privilege of attending Le Web ’08 in Paris, which was artfully composed and hosted by Loïc and Geraldine Le Meur. It was an interesting event; I always like getting an international perspective on technology and business.

What was perhaps most interesting was the constructive tension between creativity and business on display there.

The theme of the conference was love — a primary human emotion. However, many of the guests and speakers were aggressive, technically-minded business people. But many of the speakers were artists, musicians, and researchers.

I’m fascinated by the complementary roles of “right brained” activity (art, creativity, design, visual thinking) and “left brained” activity (analysis, rule-based systems, quantitative modeling, finance) in business, particularly on the Internet.

Loïc rightly justified the use of the theme of love for the conference by saying that it is the primary emotion that drives an Internet entrepreneur to give birth to a new idea or technology. Surely this is true, but I’d argue that there are deeper justifications for using an emotion as the theme for an Internet business conference.

Developing innovative Internet business ideas requires a sense of play and real play only comes about when people tap into their creative, artistic brains. Not to get all philosophic, but Immanuel Kant stated in his Critique of Judgement that real advances in art can only be made when art is undertaken for art’s sake alone, that is to say that it is done without any expectation of value, but rather is done merely to satisfy the curiosity of the artist (or designer, or researcher, or scientist).

So, all this means that Internet business people are in desperate need of right-brained influence. It’s where the ideas come from.

My friend Paola Antonelli, curator of architecture and design at the Museum of Modern Art, is quoted as saying, “Good design is a renaissance attitude that combines technology, cognitive science, human need, and beauty to produce something that the world didn’t know it was missing.” Love is surely a human need and is arguably a driver for all good design. And aren’t we all trying to design the things that the world didn’t know it was missing?

William McDonough, famed architect and designer, has stated, “Design indicates intent,” and shouldn’t our intent be to love one another and to love our planet? Isn’t that what we should be trying to achieve in designing our Internet startups?

I was interested to see how many people literally got up and left the plenary session when the subject matter turned to art or music or emotion. Some people were there strictly for left-brained content (how to raise money, how to survive the recession, etc) while others seemed to be more open to the right brained content.

Personally, I enjoyed the presentations by Itay Talgam (conductor), Chris Anderson (curator, TED), Helen Fisher (researcher on human relationships), and Robin Good (on education) the most. I’d say these were the most right brained. Things I enjoyed the least were the presentations by Messrs. Arrington and Gillmor, especially the unfortunate bickerfest that is the Gillmor Group that ended the conference. This is not to say that this kind of “left brained, rule-based” discussion doesn’t have a role, but it doesn’t generate anything really. All it does successfully is tear people apart; it’s not creative, and it doesn’t fuel anybody’s soul.

So, I applaud Loïc and Geraldine for a really creative and fun event, and one which truly gave me a sense of what is currently going on in the heads of European web entrepreneurs. I would simply encourage steering even further into the realm of emotion, creativity, design, and art – as it’s this kind of content which will pull us out of the recession, as it’s this kind of thinking that will help people create art and beauty for art’s sake alone, and these will be the innovations that the world didn’t know it was missing.

Rock on, Loïc, and let your right brain show; it’s your best side.

November 23rd, 2008 — art, design, software, trends

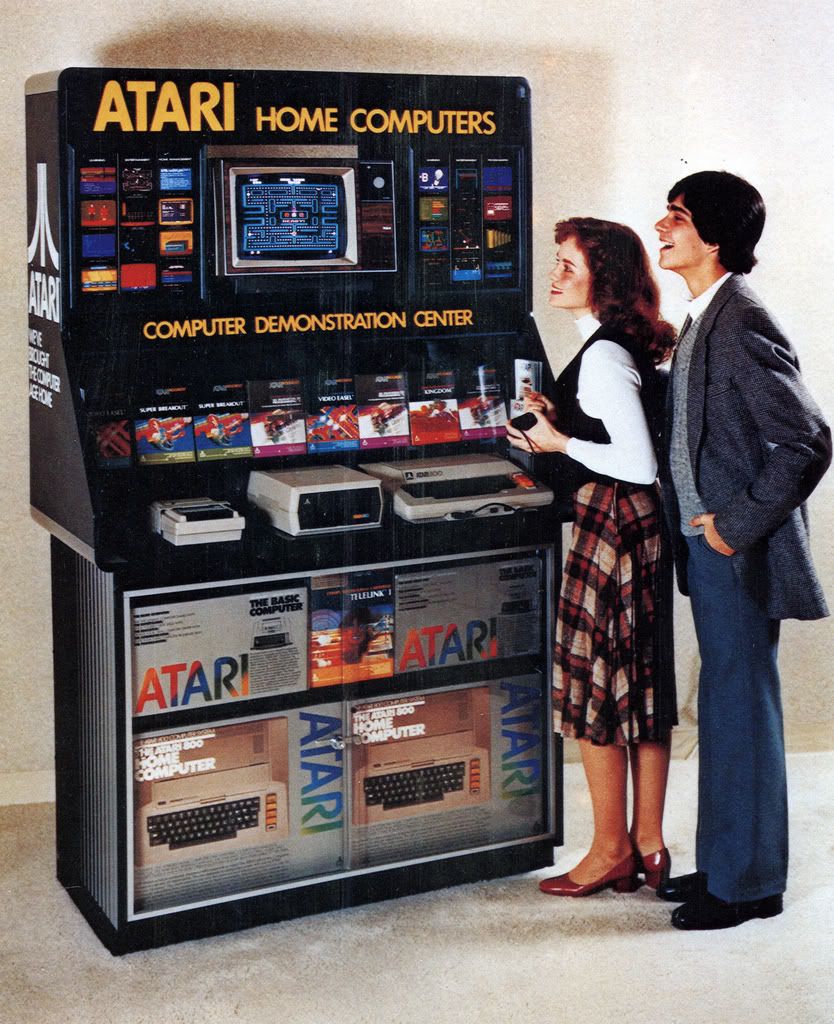

I was 5 years old in 1977, and all-in-all, I’d say the aesthetics of the day made a big impression on me. Here are some of the things that, looking back on it 31 years later, seem to share a common visual language and which were most influential on the next 10 years in movies, computing, games, and package design.

The rich colors and ground-breaking special effects of Spielberg’s 1977 Close Encounters of the Third Kind marked the beginning of a new era in filmmaking and ultimately set a goal for computer graphics and video games. The nascent digital graphics industry was barely capable of producing color “high-res” graphics, but folks knew that when they could, these were the kinds of graphic effects they wanted to make.

Maybe it’s just me, but it seems to me that Close Encounters, Atari, Space Invaders, and Star Wars were all linked together with a common visual sense. I think it’s pretty obvious that Atari ripped off Close Encounters for the Space Invaders packaging.

Likewise, the colorful “light organ” used to communicate with the aliens in Close Encounters is a close cousin, visually, to the famous Atari game Breakout. Steve Jobs was one of the designers of the arcade version of Breakout. Note the similarity to the original “rainbow” Apple logo.

Computer-generated music and sound was still in its very earliest stages, but the simple John Williams melody put to such brilliant use in Close Encounters was the sort of musical coda that aspiring game designers and programmers could latch onto and reproduce. John Williams of course scored hit after hit in movie soundtracks, but the Close Encounters and Star Wars themes of 1977 were hugely influential.

Spielberg used the Rockwell International logo (center) to clever aesthetic effect in Close Encounters; contractors at the secret military base at Devil’s Tower sported it, visually quoting the Devil’s Tower landscape. Of course, it’s interesting to note how similar the logos are for Atari, Rockwell, and Motorola – all major corporations of the day.

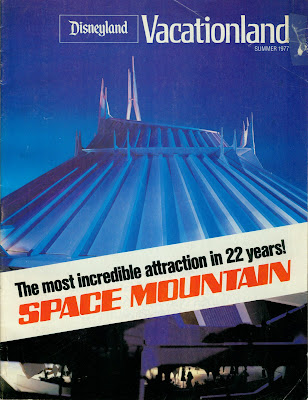

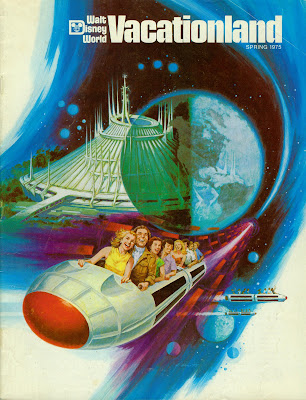

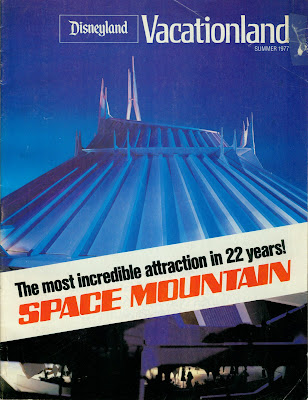

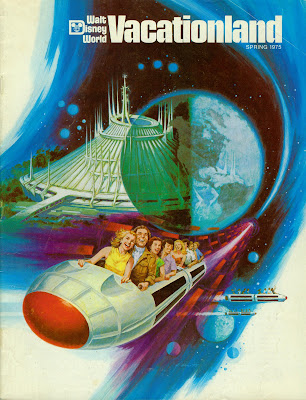

Disney got into the act in 1977 with the opening of Space Mountain. While they may not have been directly influenced by imagery from Close Encounters, Atari, or Star Wars, it’s clear that the popular imagination was drawing from common influences like Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey from 1969.

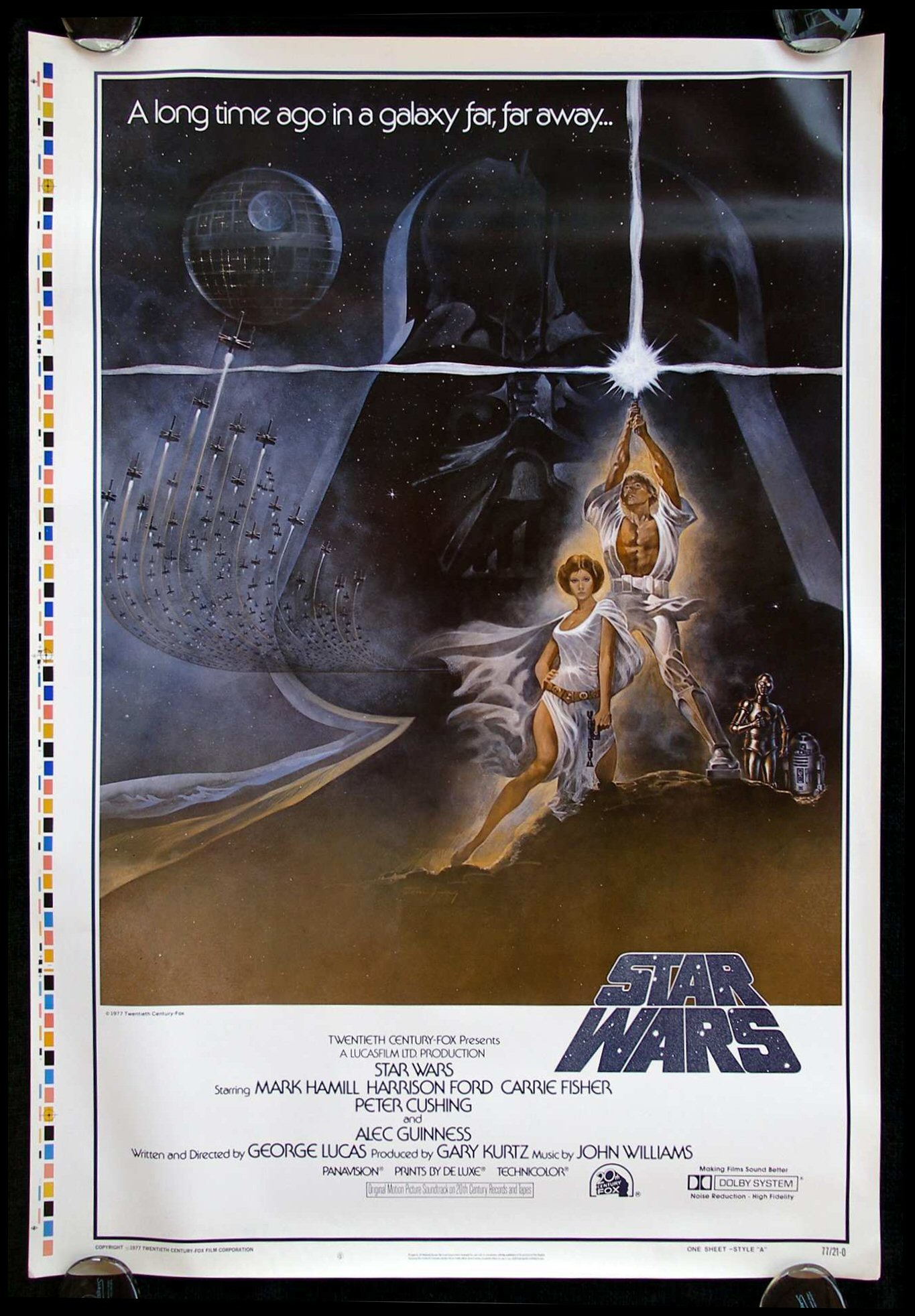

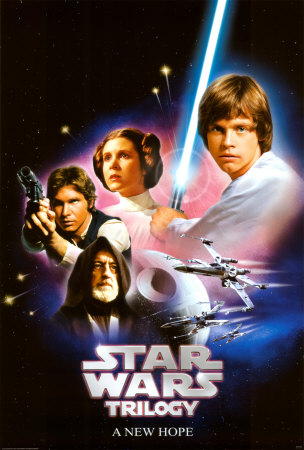

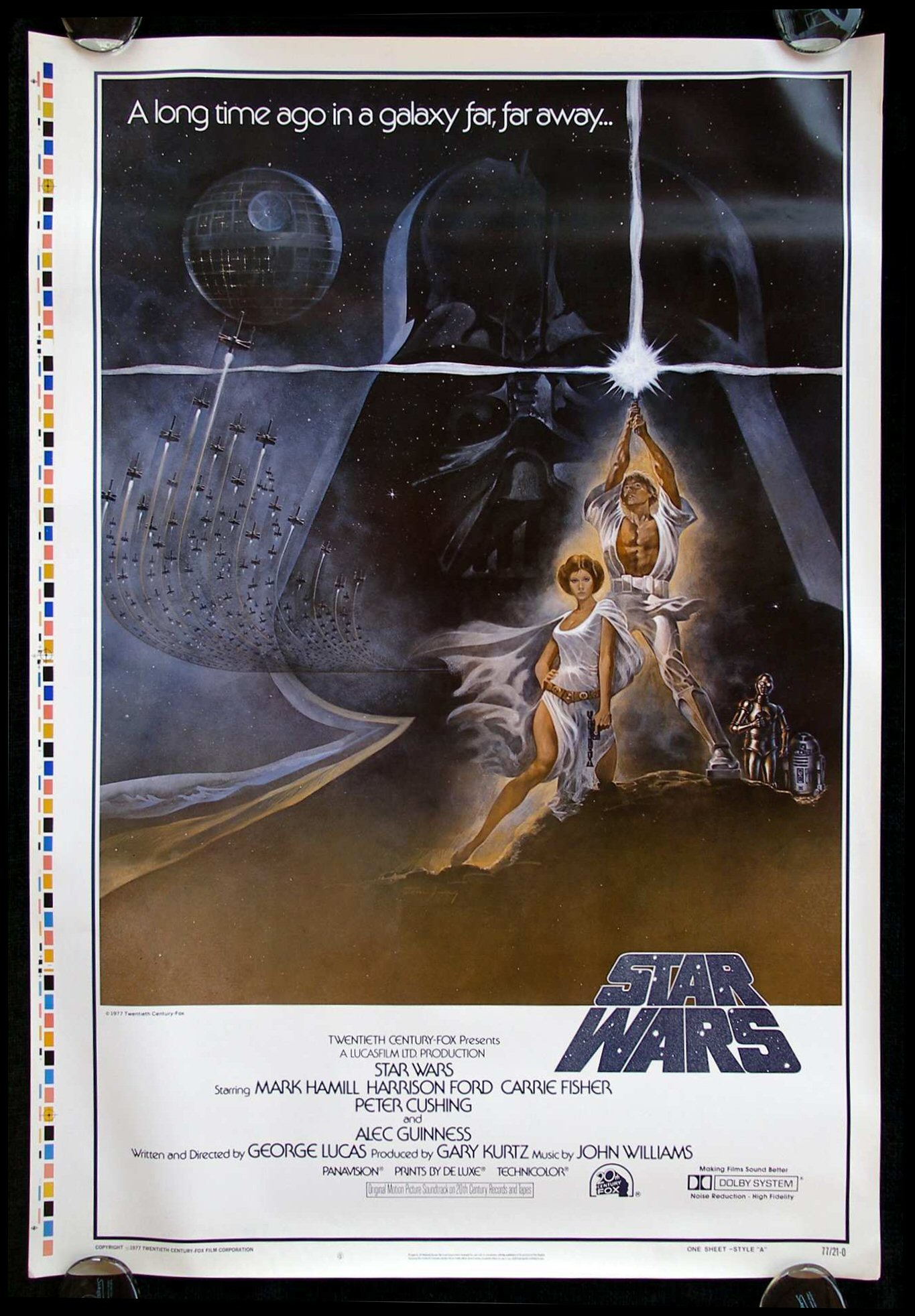

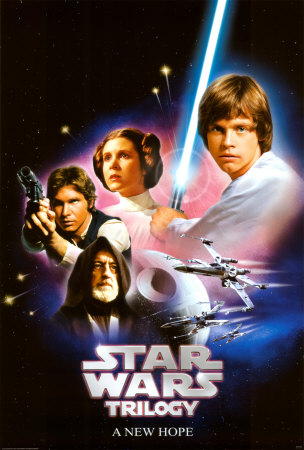

Of course the biggest influence of 1977 was George Lucas’ seminal work, Star Wars, which interestingly was not initially marketed using its iconic title graphics in its movie poster. It took a little while, and for the film to settle into its status as an international blockbuster, for it to adopt the visual marketing language that would become familiar in the release of the subsequent films in the series.

Arguably, the latter sans-serif Star Wars bubble letters were more inline with the iconography of Close Encounters, Atari, and the other major visual influencers of 1977. I’d bet the previous, blockier Star Wars graphic was designed in 1975 or 1976, before the film and its title graphics were completed. And the very earliest Star Wars art from the 1973-1974 timeframe used a hand-drawn serifed font — a different look altogether.

The dirty, realistic “used universe” designed for Star Wars was also influential. Unlike previous science fiction and space films, Lucas imparted his universe with a lived-in, beat-up look that added a romantic touch of decay to an imagined future — or past.

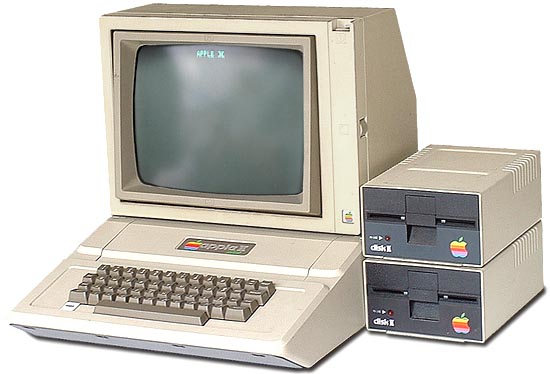

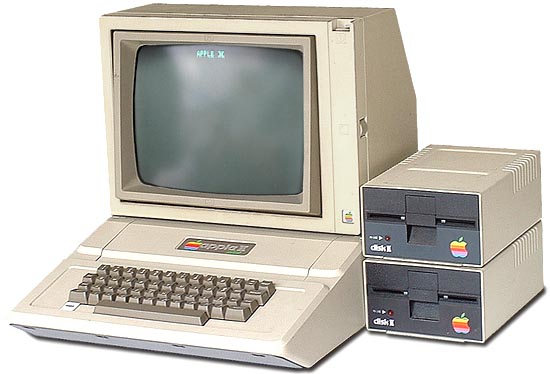

The Apple ][ was a direct result of Jobs’ (and Wozniak’s) work on Breakout, and the color graphics circuitry has much in common. And I don’t think it’s any stretch to say that the generation of Silicon Valley idealists that designed the Apple ][ and Atari 800 were hugely influenced by the blockbuster science fiction films of the day. While the early Apple designs lacked sufficient economy of scale or budget to have a very “designed” aesthetic, the Apple II does look like something straight out of the Star Wars universe. And the ugly Disk ][ and portable monitor are things that just didn’t get attention yet. Maybe they’re dirty, lived-in artifacts of a galaxy far, far away?

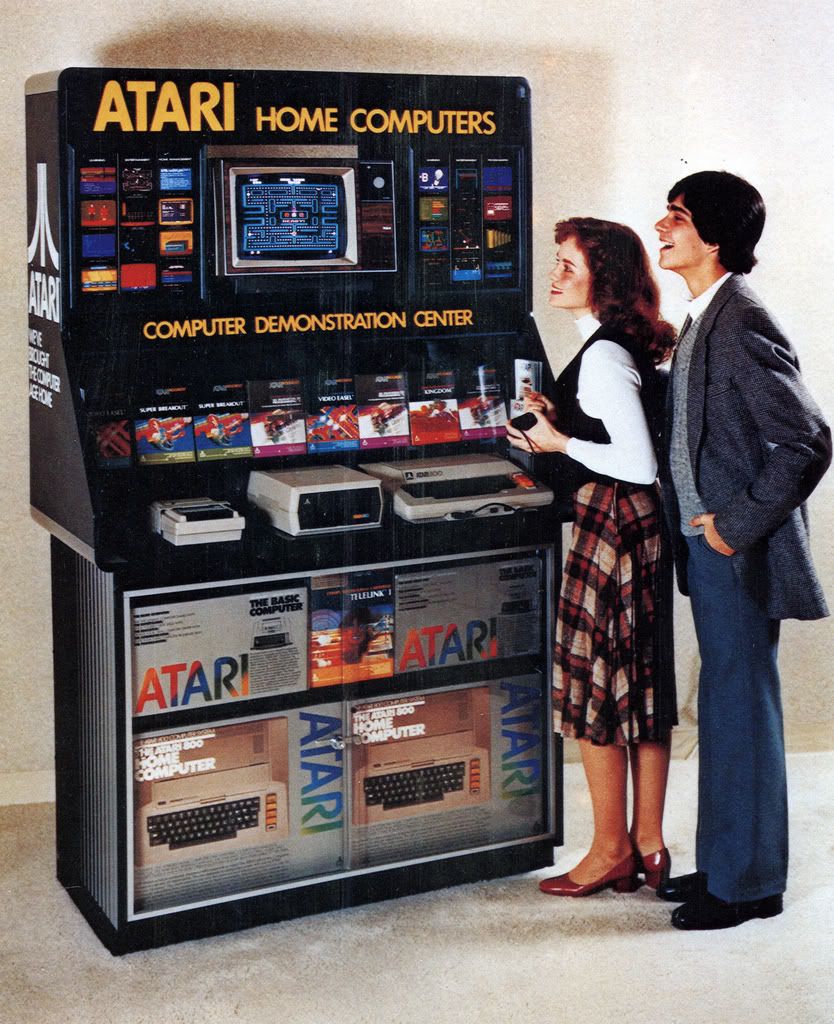

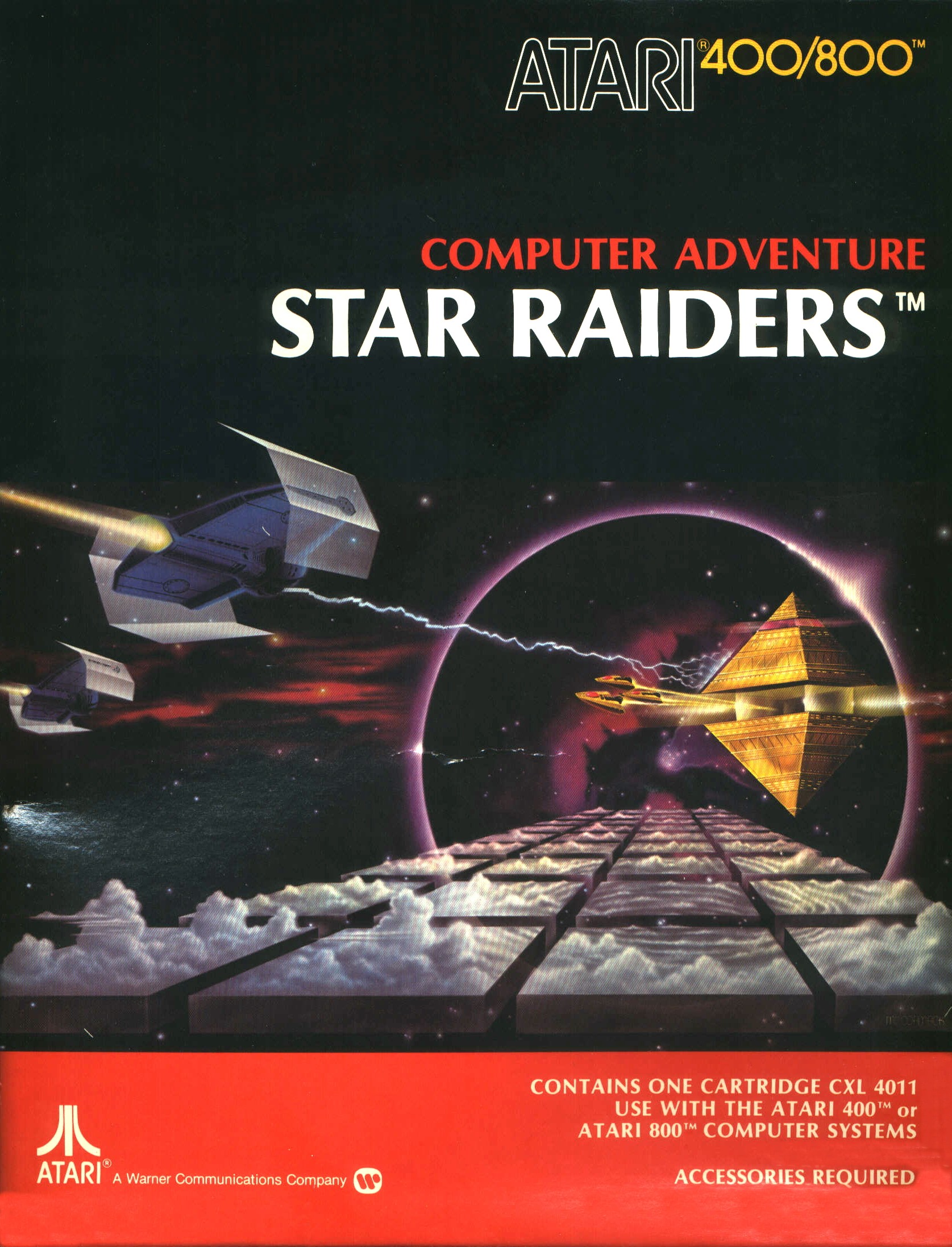

Atari, on the other hand, with the success of the 2600 VCS and its computers, had fully embraced the 1977 aesthetics and by 1980 had full color graphic packaging and a line of “Star Wars” compliant peripherals. And the packaging for the programs borrowed from movie poster designs.

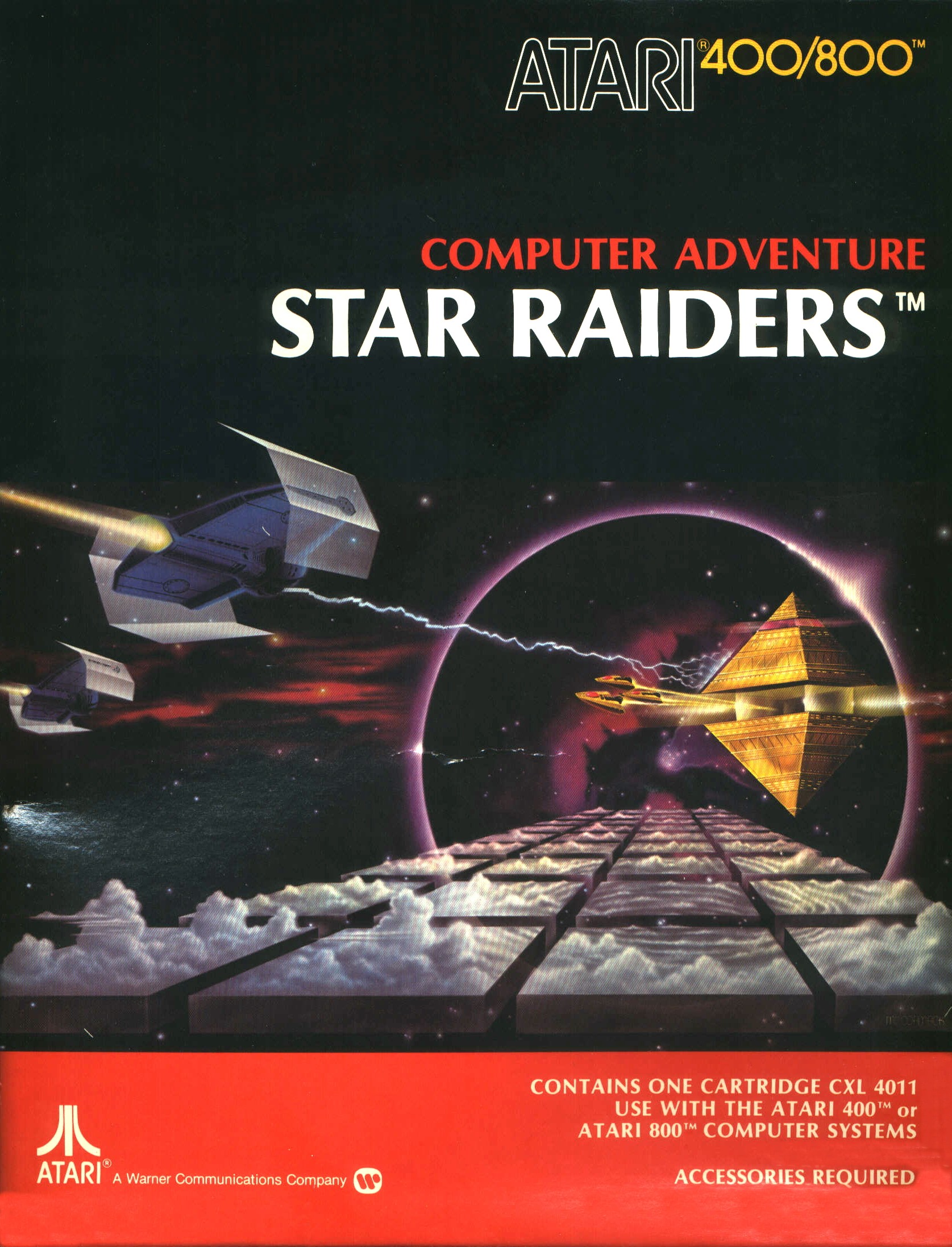

Quite clearly Star Raiders (1979) borrowed directly from Star Wars. In fact, looking at this graphic, I’m now surprised that Atari didn’t get a phone call from Lucas. I guess this was back in the day before tie fighters were Tie FightersTM.

Media critics have argued that Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind marked the start of the era of blockbuster films, and a general shift in popular culture away from smaller, more thoughtful cinema and towards a populist, anti-intellectual approach in art and film in particular.

Whether that’s true or not, I think it is fair to say that 1977 did mark the year of a seismic shift in aesthetics that has been felt all the way through today in computing, gaming, film, and product packaging. Perhaps 1977 is a kind of bright-line marker for popular art — before and after seem to be from entirely different eras.

The fact that I’ve spent most of my life selling products or working in technologies directly influenced by this powerful aesthetic sense is likely no coincidence: to be young in 1977 was to be indelibly marked by the look and feel of a new era.

November 21st, 2008 — art, business, design, economics, iPhone, mobile, programming, software, trends, visualization

At Xerox Parc in the 1970’s, Alan Kay fostered the innovations that form the foundation of modern computing. Windowing, mice, object oriented languages, laser printing, WYSIWYG, and lots of other stuff we take for granted today either had its start or was fleshed out at Xerox Parc.

The venerable mouse, which enabled direct manipulation of content on the screen, was just one of a few innovations that was screen-tested as a possible heir to the venerable cursor and text terminal metaphor which had predominated since the dawn of computing.

Mice, trackballs, light pens, tablets, and Victorian-looking headgear tracking everything from brainwaves to head and eye movements were all considered as the potential input devices of the future. No doubt there were other metaphors besides windows considered as well. Hypercard, anyone?

Steve Jobs, by selecting the mouse as the metaphor of choice for the Lisa and subsequent Macintosh computers, sealed the deal. Within a year, Bill Gates, by stealing the same design metaphor for use in Windows 1.0, finished the deed. By 1986, the mouse was a fait accompli.

Since the dawn of the Mac and Windows 1.0, we’ve taken for granted the notion that the mouse is and will be the primary user interface for most personal computing and for most software.

However, computing is embedded in every part of our lives today, from our cell phones to our cars to games and zillions of other devices around the house, and those devices have myriad different user interfaces. In fact, creating new user experiences is central to the identity of these technologies. What would an iPhone be without a touch screen? What would the Wii be without its Wiimotes? What, indeed, is an Xbox 360 but a PC with, uh, lipstick and a different user interface metaphor?

(An aside: How awesome would it be if the iPhone, Wii, and Xbox 360 all required the use of a mouse? People fidgeting on a cold day, taking out their iPhone, holding it in their left hand, plugging in their mouse, working it around on their pants to make a call. Kids splayed out on the rumpus room floor, mousing around their Mario Karts. Killer, souped up force-feedback mice made just for killing people in Halo. Mice everywhere, for the win.)

So, what’s with the rant? Simply that the web has taken a bad problem — our over-reliance on mice — and made it even more ubiquitous than it was in the worst days of windowing UI’s.

“And then if you click here…”

No, here — not over there. Click here first. Scroll down, ok, then click submit. Now click save.

See the problem? The reliance on the mouse metaphor on the web is fraught with two hazards.

- Mice require users to become collaborators in your design.

- Each user only brings so much “click capital” to the party.

Catch My Disease

We’ve all had the experience of using a site or app that requires a great deal of either time or advance knowledge to fully utilize.

You know the ones — the ones with lots of buttons and knobs and select boxes and forms just waiting for you to simply click here, enter the desired date, choose the category, then get the subcategory, choose three friends to share it with, then scroll down and enter your birthdate and a captcha (dude) and then simply press “check” to see if your selection is available for the desired date; if it is, you’ll have an opportunity to click “confirm” and your choice will be emailed to you, at which point you will need to click the link in the email to confirm your identity, and you’ll be redirected back to the main site at which point you’ll have complete and total admin control over your new site. Click here to read the section on “Getting Started”, and you can click on “Chat with Support” at any time if you have any questions.

What the hell do these sites want from you?

If these sites are trying to provide a service, why do they need you to do so much to make them work? Sure, some stuff is complex and requires information and processes and steps to empower them, but when you ask users to participate too much as key elements in your design, you create frustration, resentment, and ultimately rage. That’s cool if that’s your goal, but if you’re trying to get happy users, you’ve done nothing to advance that cause. So, it shouldn’t be about “all you have to do is click here and here.” Ask less of your users. Do more for them. Isn’t that what service is all about?

Limited Click Capital

Sometimes, people just want to be served ��— even entertained or enchanted. They don’t want to become the slavish backend to a maniacal computer program that requires 6 inputs before it can continue cialisviagras.com. Is the user in service of the computer, or is the computer serving the user? I always thought it was the latter.

I’ll never cease to be instructed by the lessons learned from developing my sites Twittervision and Flickrvision. Both sites do something uncommon — they provide passive entertainment, enchantment, and insight in a world where people are asked to click, select, participate, scroll, sign up, and activate. It’s sit back and relax and contemplate, rather than decipher, decide and interact. Surely there are roles for both, but people are so completely tired of deciphering, that having a chance to simply watch passively is a joyful respite in a world of what is mostly full of badly designed sites and interactions. This alone explains their continued appeal.

People come to sites with only so much “click capital,” or willingness to click on and through a site or a “proposed interaction.” This is why site bounce rates are usually so high. People simply run out of steam before they have a chance to be put through your entire Rube Goldberg machine. Make things easier for them by demanding fewer clicks and interactions.

Make Computing Power Work For Your Users

Truism alert: we live in an age with unprecedented access to computing power. What are you going to do with it? How are you going to use it to enchant, delight, and free your users? Most designs imprison their users by shackling them to the design, turning them into nothing more than steps 3, 6, 8, 9, and 11 of a 12 part process. How are you going to unshackle your users by making them — and their unfettered curiosity — the first step in a beautiful, infinitely progressive algorithm?

Predict and Refine

Forms and environments that rely on excessive interaction typically make one fatal assumption: that the user knows what they want. Most users don’t know what they want, or they can’t express it the way you need to know it, or they click the wrong thing. Remove that choice.

Do your best to help your users along by taking a good guess at what they want, and then allow them to refine or steer the process.

Remember, you’re the one with the big database and the computers and the web at your disposal: how are you going to help the user rather than asking the user to help you? You’re advantaged over the user; make it count for something.

Don’t Think About Mice

Mice lead to widgets. Widgets lead to controls. Controls lead to forms. Forms lead to hate. How are you going to break free from this cycle and give your users something compelling and useful with the minimum (and most appropriate) interaction? What is appropriate interaction?

It depends. What if you rely on gestures, or mouseovers, or 3 yes or no questions in big bold colors? That’s minimal and simple. It may be just what you need to empower your idea and serve your users.

I’ve been working with the WiiMote and the iPhone a lot lately, and trying to use touch screens, accelerometers, and the Wii’s pitch and roll sensors to create new kinds of interaction. Maybe this is right for your work.

Think about it and don’t assume traditional mouse/web/form interactions. Sure, sometimes they are the right and only tool for the job, but if you want to stand out and create compelling experiences, they surely can no longer be the central experience of your design.

Long Live the Cursor

Back in the early days of GUIs, there were lots of people who contended that no serious work would ever get done in a window and that the staple of computing and business would be the DOS metaphor and terminal interactions. There have been dead-enders as long as there have been new technologies to loathe. I’m sure somewhere there was a vehement anti-steel crowd.

The mouse, the window, and HTML controls and forms are the wooden cudgels of our era — useful enough for pounding grain, but still enslaving us in the end. How will you use the abundance of computing power, and new user interface metaphors to free people to derive meaning and value?