Entries Tagged 'software' ↓

October 19th, 2009 — business, design, economics, social media, software, trends

I typically hate writing about topical technology subjects, because most often it’s reactive, worthless speculation.

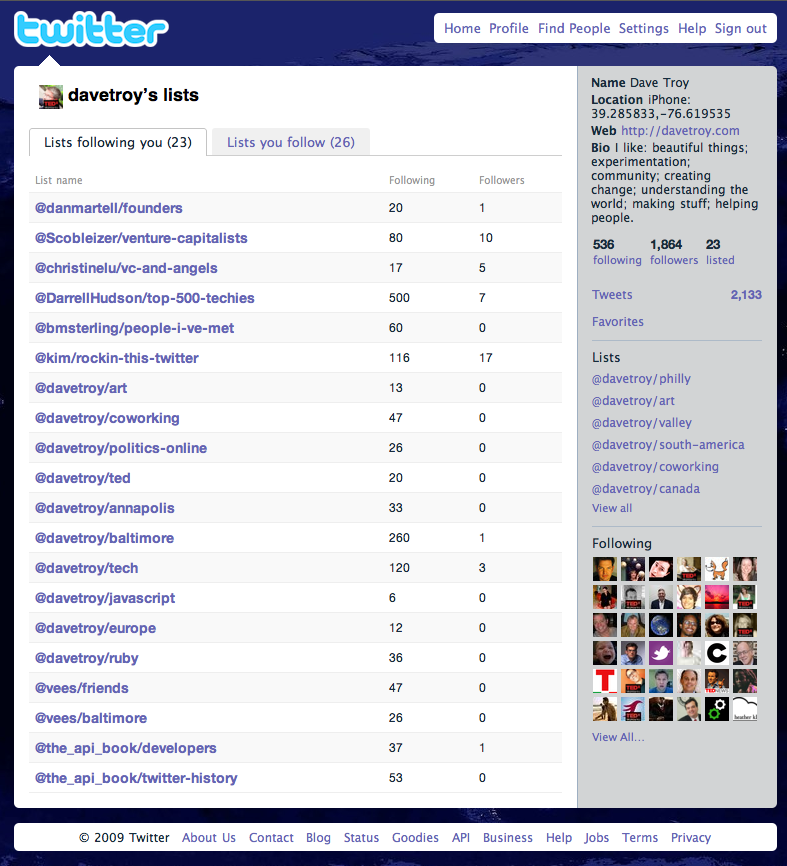

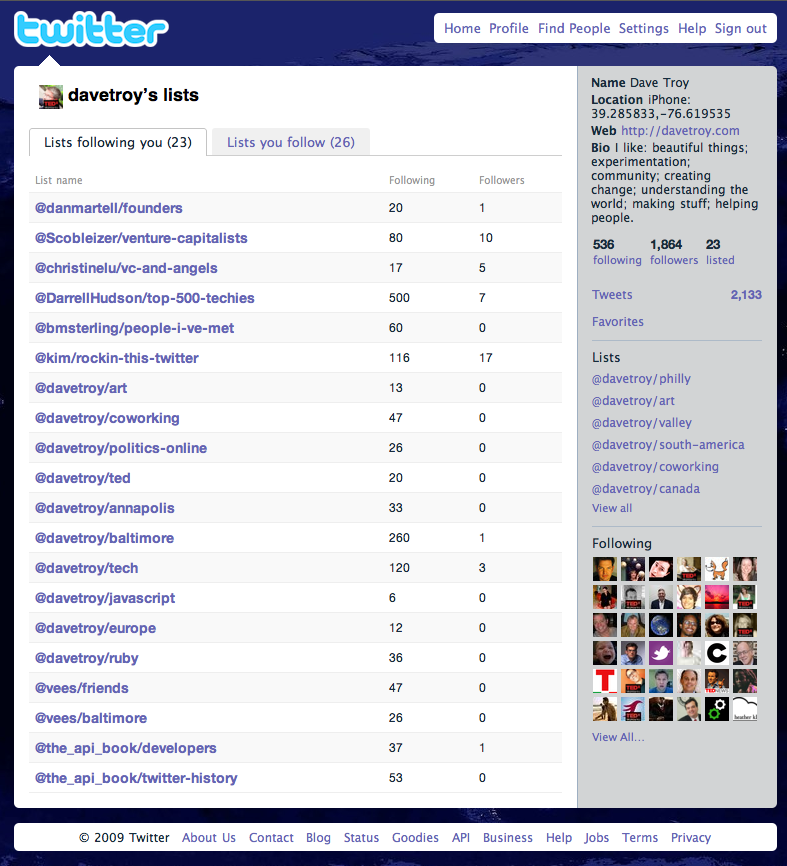

However, the new Twitter “Lists” feature has me thinking; this is an interesting feature not because of the “tech” but because of the implications on the developing economics of social networks.

First, what it is: Twitter “Lists” allows you to create lists of Twitter users that are stored within Twitter’s servers. You can name those lists (/twitter.com/davetroy/art) and those URL’s can either be public or private.

People can then follow those lists, which really is more like “bookmarking” them, as they do not appear in your Twitter stream. Those lists in turn keep track of how many “followers” they have, and you can see how many people “follow” the lists you create.

Traditional “Follower Economics” Are Dead

Jack Dorsey and Biz Stone always said that the best way to get real value out of Twitter was to follow a small number of people; it was never their intention for people to aim to follow more than 150-200 people (the “Dunbar number,” or people we can realistically expect to maintain relationships with).

With “Lists” you can add someone to a list, but not necessarily “follow” them. So, instead of “following” Ashton Kutcher, you can put him in a list that you call “actors,” or “attention whores.”

You can even put someone in a list (cool people), have them publicize that, and then change the name of that list to something less flattering (douchebags, or worse).

The issue of derogatory lists alone is one that Twitter will need to address.

So traditional “follower counts” are going to be meaningless – instead of “followers” people are going to start talking about “direct followers,” “indirect followers,” and “being listed.” It’s all changing, and I applaud Twitter for being willing to throw the old (flawed) assumptions about follower economics entirely out the window in favor of a new approach.

Buying Influence and Reputation

Within a few hours of the introduction of “Lists” I was put onto a few:

- @danmartell/founders

- @Scobleizer/venture-capitalists

- @christinelu/vc-and-angels

- @DarrellHudson/top-500-techies

- @kim/rockin-this-twitter

- @the_api_book/twitter_history

This early “seed” of my reputation is quite flattering and arguably pretty powerful (though a fraction of what I expect my ultimate “listings” will be). It shows that I am an “investor” and a “techie,” and considered so by some pretty influential people. I did nothing to influence this and would not consider doing so.

But, I am lucky and glad to have been so-described this early on. What if I really wanted to influence what lists I was on, or to appear on as many lists as possible? I can imagine now the jockeying to get onto the lists of all the “A-List” digitalistas will be intense and powerfully ugly.

Imagine the seedy things that might go on at tradeshows in exchange for getting “listed.”

Going forward, the primary question will be which specific lists you appear on (influence of curator, quality, scarcity) and, secondarily, how many lists you appear on (reach, influence).

“1M Followers” will be replaced by “listed by over 50,000,” or even “listed by the top 10 most influential people in microfinance.” And yes, listing counts will be a fraction of follower count, as lists will necessarily divvy up the people you follow through categorization.

Scarcity: You get 20 lists

It looks like people are allowed just twenty lists right now. That’s undoubtedly a scaling and design decision by Twitter to keep things manageable.

Putting aside for a moment all the reasons why people might want more than 20 lists, let’s accept the limitation. You get 20 lists. So it’s a scarce resource. It means Scoble, Kawasaki, Gladwell, Brogan, Alyssa Milano, Oprah, Biz, etc, all each get just 20 lists.

What will someone pay to get onto one of these lists?

Do you think that an author would pay to get onto twitter.com/oprah/incredible-writers? Yeah, I do too. Now imagine that, writ large, and scummier, with people even less reputable than Oprah. Now you see what I’m talking about.

At least buying followers is a scummy behavior that’s amortized over millions of targets; buying 1/20th of one particular follower’s blessing could lead to very high prices and extremely unsavory dealings.

The Coming “Curatorial Economy”

Twitter is doing this thing, and whatever Twitter does in house trumps anything that a third party developer might do, period. So, stuff like WeFollow, etc, your brother’s cool thing he’s making, Twitter directories: they are done, people. Or these external things must at least accept the reality of Lists and what they mean to the ecosystem.

Some folks have been complaining about the user interface for list management, etc, and that’s all moot: it will be available through the API, and you should expect list cloning, lists of lists, mobile client support, etc, pretty soon.

But the genie is out of the bottle. Start managing your reputation in a way that’s authentic and ethical and stay on top of this. And be prepared for what I’m calling the “curatorial economy.” (You heard it here first.)

Everybody’s making collections, and there are certainly people who will pay and be paid for listings. Count on it.

September 29th, 2009 — baltimore, business, design, economics, social media, software, trends

This was originally written as a guest post on Gus Sentementes’ BaltTech blog for the Baltimore Sun.

What if there was a place where freelancers, creatives, entrepreneurs, and financiers could meet up to collaborate on up-and-coming startup ideas? That place exists today, and it’s called Beehive Baltimore.

On October 1st, Beehive Baltimore will celebrate its first nine months of operation as a coworking facility, located in the Emerging Technology Center in Canton.

If you’re not familiar with coworking, it’s a shared workspace for creative professionals who might otherwise work at home or in a coffee shop. These days, anyone who works primarily via laptop and the internet is a great candidate for coworking!

Beehive Baltimore opened February 1, 2009 specifically to cater to these kinds of professionals, and the Beehive community now has over 40 members including people in web design, programming, marketing, public relations, finance and other information-based industries.

Last Thursday, we held an open house at the Hive for prospective members and others in the community to stop by, meet some of our members, and find out more about what coworking is all about.

Beehive is designed to be a community of peers, and does not aim to make a profit. Working in partnership with the Emerging Technology Center in Canton, Beehive aims to connect freelancers, seasoned entrepreneurs, and other professionals via long-term relationships that lead to mutual benefit – and possibly to new startups!

The Hive (as we call it) has also already given birth to multiple events and meet-ups that might not otherwise have a place to meet. Some of the groups that we either have hosted or have helped create include:

- Baltimore Angels (an angel investment group)

- Baltimore Hackers (a computer language study group)

- Baltimore/Washington Javascript meetup

- Baltimore Flash/Flex User Group (a group for users of Adobe’s Flex platform)

- Refresh Baltimore (a web professionals group)

- Barcamp Baltimore (a user-generated tech conference)

- TEDxMidAtlantic (coming on November 5th)

On October 1st at 12pm, Beehive Baltimore will host its first “Show and Tell” event, where participants are invited to share their projects, startups, or prototypes and get feedback from the group.

And on October 15th, Beehive Baltimore will be recognized by the Maryland Daily Record as an “Innovator of the Year.”

Several Beehive members and affiliates will be providing some guest posts for BaltTech over the next two weeks while Gus Sentementes is on vacation. So stay tuned for some voices from the Hive over the coming days!

Beehive Baltimore is part of a large coworking movement. Hundreds of cities all around the world from Los Angeles to Charlotte to Paris to Shanghai have implemented coworking facilities, and we see ourselves as connected to these communities.

And so coworking looks to be an integral part of the tech startup ecosystem – where entrepreneurs, creative talent, and angel investors can all come together to talk about the Next Big Idea.

To find out more about Beehive Baltimore, visit http://beehivebaltimore.org or email info@beehivebaltimore.org.

April 4th, 2009 — business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, software, trends

We teach entrepreneurs that they should pick an idea they are passionate about, work up a business plan, assemble resources and then execute it.

If we think about entrepreneurialism as a kind of gardening, this traditional approach in a sense encourages people to plant monocultures that are extremely vulnerable to disease. Furthermore, who wants a garden with just one kind of plant in it? Lastly, if the “idea” you choose to plant cannot grow well in your location or your climate, or the climate changes, you are left with a failed crop of your monoculture, and little recourse but to bankrupt yourself and start over.

Any gardener will tell you that putting together a good garden requires a kind of “flow” — getting “in the zone” to think about what plants will work where, what plants will complement each other, and how timing and horticultural relationships will play out to produce a garden that is maximally rewarding, whether those rewards are aesthetic or culinary.

Gardeners know what plants are native to their place, which require sun or shade, which are susceptible to parasite damage, and how to combine plants to achieve symbiotic results. They know how tightly certain plants should be planted, which ones need thinning, and which ones must be started as seedlings.

What you rarely see is a skilled gardener go out and plant a monoculture of, say, beets. Beets by themselves require a specialized kind of farming. A certain kind of soil. To really get a lot of beets, you need to apply particular pesticides and take a particular approach. And when the crop matures (assuming your bet on the conditions and climate pay off), you’ve got just one thing: beets. And, let’s face it: it’s pretty easy to get sick of beets.

“Pushing rocks uphill sucks.” – Sisyphus

In Greek mythology, Sisyphus was sentenced to push a boulder up a hill, only to watch it roll back down so he could push it again for all of eternity. This is a decidedly bad gig. Some businesses are like this too, and too many well-meaning, intelligent entrepreneurs spend time on these kind of Sisyphean enterprises – consuming a lot of precious resources and never getting traction.

In business, there are rocks to push sometimes: hard work is always part of doing something worthwhile. But successful businesses always reach the summit and get to watch the rock roll down the other side.

This is when business is fun. The world seems to love what you’re doing. People are clamoring to work for and with you, the press thinks you’re great, and the money keeps rolling in. New opportunities and ideas emerge at every turn and the sky seems to be the limit.

Great as these conditions are, they rarely last. Businesses nearly universally reach inflection points where their products fall out of favor or stop fulfilling a market need. They become old news, and seemingly out of nowhere, the business is pushing rocks uphill again – usually to the great surprise of management, investors, and customers.

When you’re pushing rocks uphill, you know it. Everyone knows it. The press remarks on it, and just as when things are going well you seem to be in an upward spiral of success, these conditions seem to dictate a downward spiral of failure. These times can be quite dark. Often, they can be sustained and overcome, until you reach a new summit where conditions have changed so that your boulder can roll freely downhill. But many don’t have the stomach to persist through these dark times. “Business turnaround experts” are really just people who can see what’s necessary to minimize drag and reposition a company to that next summit, where more favorable conditions can prevail again.

Towards a New Entrepreneurship

The old model of entrepreneurship creates arranged marriages between entrepreneurs and ideas, and these marriages often don’t work out. After years of struggle, they often end in disaster, and only in extremely forgiving climates do the entrepreneurs get a chance to even re-marry. Quite often, the entrepreneur decides to become celibate and return to its abusive relationship with The Man, while sometimes the wild-eyed ones manage to persist through a couple more failures before finally hitting upon a success.

According to this article based on a report by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the predicted success rate for first-time entrepreneurs is just 20.9%. That’s a one-in-five shot. Even more telling, the results for experienced entrepreneurs is not much better. Entrepreneurs with a track record of success see a 30.6% success rate on average, while serial entrepreneurs who failed in their prior venture are only successful 22.1% of the time on subsequent ventures. To pick a round number, these data show that about 75% of all startups fail.

Is this the best we can expect from the great capitalist engine? What if we could do better? How that might work?

You Don’t Suck – Your Idea Sucks

The data above tell us that experience doesn’t count for that much. In fact, ostensibly it counts for at most a 9.7% improvement in odds. Not a bad gain, but what if it’s an illusion? If an experienced entrepreneur and a first-time entrepreneur chase the same idea, I’d argue the odds of success are roughly equivalent. The only difference between a first-time and experienced entrepreneurs is that they have a better sense about what ideas to chase — and even that discernment may only count for a 9.7% improvement.

So the advice to all entrepreneurs thus becomes essentially the same: pick ideas that will work in the marketplace and expend resources only on those ideas.

Of course, this is easier said than done. How do you know what ideas will work? How can people try a lot of ideas without bankrupting themselves or running themselves ragged?

Starting a Garden of Ideas

First, we have to accept the fact that as individuals, people are really bad at knowing what ideas will work in the marketplace. This is the primary reason for the 75% failure rate we see amongst entrepreneurs. It’s also the reason why top-down planning failed in the Soviet Union. As a general rule of thumb, assume you know a lot less than you think you do about what ideas will work and what ideas won’t, because you’re likely wrong. So are your friends, your family, your trusted advisors, and other more experienced entrepreneurs.

Start thinking instead about what you want your idea garden to look like. What ideas motivate you, and fill you with a sense of childlike wonder? What ideas give you inner peace and create a sense of aesthetic fulfillment? What higher causes do you aspire to? What causes do you think you can motivate others to rally around? With these questions, you can start to get a sense of what you might start to try in your idea garden.

Resonance

Today, we have tools to test the resonance of ideas with fairly wide audiences — for free. Twitter, Facebook, the web, and other mechanisms allow us to expand our networks to find people to bounce our ideas off of. Start bouncing your ideas — the ideas you’re most passionate about — off of a wider audience. Put out feelers. See what sticks.

This wider audience should consist of at least a few hundred people, ideally, and you will get a sense of what ideas move people by listening to peoples’ reactions. If you don’t have an online audience of a few hundred people yet, start thinking about how to get one. Go to meetups and other events. Follow people online whose opinions you trust. Build up a good-sized audience and listen to what they tell you about your ideas.

Ideas Are Cheap

You may worry that sharing an idea with people will “let it out of the bag” and someone else will “steal it.” You’re not so smart to have come up with an idea that no one else has thought of before. Really — believe that. Look through the US Patent Office site sometime and you’ll get a sense for just how cheap ideas really are.

What you must have that is unique and irreplaceable is the vision, passion, and relationships required to bring your idea to fruition.

But the idea itself — the raw two or three sentences that define your concept — has very little potential by itself. By sharing your idea with others, you can strengthen it. Others can contribute to it, pointing out the places where it’s weak, and repurposing it in ways you never imagined. Don’t be afraid to share your ideas, in whole or in part, so that others can help you bring them to fruition.

It could be that you do not want to put all your cards on the table at once. That’s fine. If your idea can be broken apart and tested amongst audiences that way, that can be a way of making your ideas public without disclosing the entire concept. This can be a valid approach when dealing with concepts that require patent protection. But those ideas are much rarer than you think.

You can expect that you will break down and reassemble your own ideas repeatedly before they make it to the market. It’s quite likely that you’ll combine the “resonant” parts of two ideas into one cohesive concept (CD’s by mail bad, DVD’s by mail good) that resonates in the marketplace. Be willing to play around with your ideas and allow them change over time.

Waiting It Out

One of the reasons the success rate for startups is so low is that we have taught entrepreneurs to set up housekeeping with the first viable idea they encounter. The societal pressure to be doing something (so, what are you up to these days anyway?) is very great and people want to perceive and project themselves as successful.

Idea Gardening is something that we as a society have decided is only a valid occupation for people like Richard Branson or Oprah Winfrey. And even they have specific ongoing successes that they can point to that seem to validate their modi operandi.

Gardening takes time — time for sunlight, for seed, for rain to converge in fecundity. The same is true of Idea Gardening. Patience is required for ideas, people, and resources to converge in a way that releases stored energy. If you’re having to use too much pesticide (lawyering) or fertilizer (cash) to make your idea work, you’re likely going against the forces of nature, and not taking advantage of the energy of the marketplace.

Don’t overextend yourself by sinking resources into the first idea you have that looks to be viable. As a committed gardener, you will have many sprouts and leads that are viable. Put your attention to the ideas that seem to be the strongest, and use all of your available resources to drive multiple ideas forward in parallel. Otherwise you’ll have the kind of fragile and brittle all-beet monoculture that will have a hard time surviving market conditions.

Over time, you will find that there are projects that you need to cull. Often, an idea is just premature for the market. But that doesn’t mean you can’t nurture it and keep it going in some form until conditions are right. Often, that is not a very expensive proposition and if you are passionate, it can be very fruitful in the future.

Sunk Costs

People are suckers for sunk costs; this is the instinct that makes folks want to double down in Vegas to recover their losses. But losses are losses, whether measured in time or in money, and chasing after a failed idea to recover yourself to some perceived baseline is a mistake.

In the past, entrepreneur failure often meant sunk costs in the form of infrastructure and time wasted. These sunk costs could run into the hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars. Entrepreneurs, wanting to perceive themselves as successful, very rarely will walk away from this kind of situation willingly or rationally. Likewise, investors (less often) sometimes fall into the same trap. It’s these kinds of sunk costs that keep good money chasing after bad in countless businesses.

Clearly the only rational thing to do is to stop burning money and move on to something that will work. It’s not your fault it didn’t work out — the market didn’t want what you were selling. So, without pride or prejudice, stop the bleeding and move on. It may be your idea is still viable, but it might be viable for someone else, someplace else, at some different point in time. Put it on ice and return to it then.

The key to avoiding the trap of sunk costs in the Idea Gardening model is to minimize costs until an idea looks to be viable. If you have 10 ideas you’re experimenting with, and 4 show promise, what can you do to put a minimal amount of investment in only those four that will advance them to a stage where you can learn more about their prospects?

After that round, it may be that only two show promise at that moment. What can you do to put a minimal amount of investment in only those two ideas that will advance them? It may be that one of those ideas is really ready to explode and is ready to accept a major investment. Do that. By adopting this methodology, all of your investments will be right-sized and appropriate to advancing your concepts. With the disciplined use of this approach, one could theoretically achieve a 75+% entrepreneurial success rate , rather than a 75% failure rate!

This is an entirely different approach to entrepreneurship. For the software developers out there, this is the agile approach to business. Start small, iterate, and follow the market need. This also means that failures, when they occur, happen quickly. And that is the best thing any entrepreneur could hope for.

Cost Control

Besides for only investing time and money into ideas that have promise, it is now more possible than ever to experiment with concepts for very low costs. Free, open source software like Ruby on Rails, PHP, MySQL, and Linux have made it possible to prototype complex concepts extremely inexpensively. If you know how to code the ideas yourself, you can lower costs even further. An entrepreneur who is also a software developer is uniquely positioned to try out dozens of ideas and let the market decide which ones will work.

Additionally, phone services like Google Voice and various other outsourced business services ranging from PayPal to GetFriday and Amazon Mechanical Turk enable incredible things to be done at rock-bottom prices. Cloud computing resources like Amazon EC2 and S3, and Google’s App Engine allow for fast and affordable scaling of ideas at very reasonable prices.

There has never been a better time to be a technology entrepreneur but many of the same forces help all entrepreneurs keep costs down. You won’t get trapped by sunk costs if they are very low; you will walk away from $10,000 sooner than you will $100,000 or $500,000.

More Thomas Edison than Henry Ford

Many of the great industrial entrepreneurs of the last 100 years have been uniquely positioned — as much by accident as by anything else — to capitalize on emergent trends. Carnegie, Mellon, Fricke, Rockefeller, Henry Ford, Bill Gates, and Steve Jobs, all took advantage of (and helped to create) massive trends that could be pushed through society and thereby capitalized on.

You’re not those guys. The odds of any of us finding some “megatrend” that we can exploit profitably for very long are quite slim.

Look instead to Thomas Edison’s approach.

Edison put himself into the Idea Gardening business. His labs in Menlo Park, New Jersey were a virtual playground for engineers. They generated more than 1,500 patents and went on to form General Electric. He was famously quoted as saying that “Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration,” but this is often misunderstood.

Edison wasn’t saying that entrepreneurship was driven by “hard work” of the Sisyphean kind — no one can sustain that kind of load and be that prolific. Rather, he was suggesting that the hard work of invention lay in hoeing the rows and planting countless seeds of innovation so that, in time, the best ideas could bear fruit and thereby transform the world.

So entrepreneurs, plant your gardens. Give them sun, water, and time. The rest will follow, and you, too, will go on to transform the world.

Many thanks to Bill Mill, Mike Subelsky, Gus Sentementes and Jennifer Troy who thoughtfully reviewed this essay.

February 8th, 2009 — baltimore, business, design, economics, philosophy, programming, social media, socialdevcamp, software, trends

Twice last year, I had the experience of putting together SocialDevCamp East, a barcamp-style unconference for software developers and entrepreneurs focused on social media.

Sounds straightforward enough, but that sentence alone is jam-packed with important design decisions. And those design decisions carried through the entire event, and even into its long-term impact on our community and our community’s brand. I’ll explain.

Barcamp-Style Unconference

In the last few years, the Barcamp unconference format, focused on community involvement, openness, and attendee participation has gained a lot of traction. I won’t write a ton here describing the format and how it all works as that’s been done elsewhere, but the key point is that this is an open event which is supported by and developed by the community itself. As a result, it is by definition designed to serve that community.

So what are some other design implications of choosing the Barcamp format? Here are two big ones.

First, anyone who doesn’t think this format sounds like a good idea (but how will it all work? what, no rubber chicken lunch? where’s the corporate swag?) will stay away. Perfect. Barcamp is not a format that works for everybody – particularly people with naked corporate agendas. It naturally repels people who might otherwise detract from the event.

Second, the user-generated conference agenda (formed in the event’s first hour by all participants voting on what sessions will be held) insures that the day will serve the participants who are actually there, and not some imagined corporate-sales-driven agenda that was dreamed up by a top-down conference planning apparatchik three months in advance.

The fact that there are no official “speakers” and only participants who are willing and able to share what they know means that sessions are multi-voiced conversations and not boring one-to-many spews from egomaniacal “speakers.”

The Name: SocialDevCamp East

We could have put on a standard BarCamp, but that wasn’t really what we wanted to pursue; as an entrepreneur and software developer focused on the social media space, I (and event co-chairs Ann Bernard and Keith Casey, who helped with SDCE1) wanted to try to identify other people like us on the east coast.

We chose the word Social to reflect the fact that we are interested in reaching people who have an interest in Social media. It also sounds “social” and collaborative, themes which harmonize with the overall event.

We chose the wordlet Dev to indicate that we are interested in development topics (borrowing from other such events like iPhoneDevCamp and DevCamp, coined by Chris Messina). This should serve to repel folks that are just interested in Podcasting or in simply meeting people; both fine things, but not what we were choosing to focus on.

Obviously Camp indicates we are borrowing the Barcamp unconference format, so people know to expect a community-built, user-driven event that will take form the morning of the event itself.

We chose East to indicate that a) we wanted to draw from the entire east coast corridor (DC to Boston, primarily), and b) we wanted to encourage others in other places to have SocialDevCamps too. Not long after SDCE1, there was a SocialDevCamp Chicago.

Additionally, our tagline coined by Keith Casey, “Charting the Next Course” indicates that we are interested in talking about what’s coming next, not just in what’s happening now. This served to attract forward-looking folks and set the tone for the event.

The Location

We wanted to make the event easily accessible to people all along the east coast. Being based in Baltimore, we were able to leverage its central location between DC and Philadelphia. Our venue at the University of Baltimore is located just two blocks away from the Amtrak train station, which meant that the event was only 3 hours away for people in New York City. As a result had a significant contingent of folks from DC, Baltimore, Wilmington, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, many of whom came by train.

Long Term Brand Impact

These two events, held in May and November 2008, are still reverberating throughout the region’s community. At Ignite Baltimore on Thursday, SocialDevCamp was mentioned by multiple speakers as an example of the kind of bottom-up grassroots efforts which are now starting to flourish here.

The event has the reputation of having been a substantive, forward-looking gathering of entrepreneurs, technologists, and artists, and that has gone on to color how we in the region and those in other regions perceive our area. Even if it’s only in a small way, SocialDevCamp helped set the tone for discourse in our region.

Design? Or Just Event Planning?

Some might say that what I’ve described is nothing more than conference planning 101, but here’s why it’s different: first, what I’ve described here are simply the input parameters for the event. Writing about conference planning would typically focus on the logistical details: insurance, parking, catering, badges, registration fees, etc. Those are the left-brained artifacts of the right-brained discipline of conference design.

Everything about the event was designed to produce particular behaviors at the event, and even after the event. While I make no claim that we got every detail perfect (who does?), the design was carried out as planned and had the intended results. And of course, we learned valuable lessons that we will use to help shape the design of future events. Event planners should spend some time meditating about the difference between design and planning; planning is what you do in service of the design. Design is what shapes the user-experience, sets the tone, and determines the long-term value of an event.

More to Come

I’ve got at least 3 more installations in this series. Stay tuned, and I’d love to hear your feedback about design and how it influences our daily experience.

WARNING – GEEK/PHILOSOPHER CONTENT: It occurs to me that the universe is a kind of finite-state automaton, and as such is a kind of deterministic computing machine. (No, I was not the first to think of this.) But if it is a kind of computer, then design is a kind of program we feed in to that machine. What kind of program is it? Well, it’s likely not a Basic or Fortran program. It’s some kind of tiny recursive, fractal-like algorithm, where the depth of iteration determines the manifestations we see in the real world.

As designers, all we’re really doing is getting good at mastering this fractal algorithm and measuring its effects on reality.

See you in the next article!