October 9th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, trends

Some have predicted that high energy costs, either due to decreasing supply of oil or costs associated with carbon emission mitigation, will soon push people out of their cars and onto public transportation.

But there’s something else happening: people are getting sick of spending time in transit at all, making city living increasingly attractive. We are now increasingly able to infill “scrap-time” during our days with useful activity, and location-based social networks make it possible to maximize personal connections as we move about. We are engineering our own serendipity to generate real value from every moment. Why would we squander that potential by spending time in transit of any kind?

In the future, I predict:

- Air travel will be reserved for trips greater than 500 miles

- Trains will be used for trips less than 500 miles

- Bicycles, walking, and local transit will be used within cities

- Any local trip longer than 20 minutes will be seen as burdensome

- Cars will be seen as a luxury to be used for road-trips + utility hauling

And again, this will not happen due to fuel scarcity alone – it will happen because people demand it; and I’m not talking about you – but your kids and grandkids.

Regardless of what happens with fuel prices, we know that roads do fill to their available capacity. And then that’s it. Expansion does not help for long, because roads then fill to whatever capacity is available and development occurs until roads are too broken to use.

Roads are also increasingly expensive to build. A major construction project such as the popular-but-doomed Intercounty Connector in Maryland will cost over $2.6Bn to build. Is this a good long-term use of resources? Seems to me we’re throwing a bone to some 55 year-old commuters who have been annoyed with the state of the Washington Beltway since it was built, and this is the only solution they thought could fix it. Enough with the reductionist, idiotic causal thinking already: it’s a dumb idea. I don’t begrudge it, but in the long term, who cares?

The idea-driven creative industries that America has hung its hat on can only thrive in cities, where people can get together and trade ideas freely. Any barrier to that exchange lowers the potential net economic value. Put simply, all of this kind of creative work will happen in cities. Period. Because if we don’t do it in cities, we won’t be able to compete with our peers around the world who will be doing this work in cities.

So, what of the suburbs? In many European cities, the urban centers have been long reserved for the upper-class elites; poorer immigrants, often Turks and other Islamic communities, tend to inhabit the outer rings of the city – denying them crucial access to economic opportunity. This kind of social injustice is baked into many European cultures; in France, you are simply French or not French, and no amount of economic mobility will allow someone who is not of that world to sublimate into it.

This is not the case in America. We are all Americans, and even marginalized citizens are able to fully participate in all levels of our culture – though certainly there is social injustice that must be overcome.

Over the next 50-75 years, there will be a net gain of wealthier people in America’s cities and also a net gain of poorer people in our suburbs. This will be a natural byproduct of an increasing demand to be in cities, and an increasing (and aging) suburban housing stock coupled with roads that no longer function.

To fulfill our challenge as Americans, we must use these dual gradients in our cities – the inflow of the rich and the outflow of the poor – as an opportunity to maximize social justice. By avoiding flash-gentrification and fixing education as we go, we can in a span of 20-40 years (1-2 generations) offer millions of people a pathway into new opportunities that stem from real, sustainable economic growth; all the while realizing this is going to mean more color blindness all around – and that suburbs will generally be poorer than the cities.

In my home state of Maryland, the only foreseeable damper on this force is the federal government and the massive amount of money it injects into industries like cybersecurity and other behemoth agencies like the Social Security Agency.

Because these agencies and the companies that service them generally do not have to compete globally to survive, they can locate in the suburbs and employ people that live in the suburbs – and subsidize all of the inefficiency, waste and boredom that comes with that.

This is nothing but a giant make-work program and its benefactors are little more than sucklings on the federal government’s teat, which is spending money that will likely come straight out of your grandchildren’s standard of living. Right on.

Cybersecurity, for all its usefulness in possibly maybe not getting us blown up by wackos (bored wackos from the European Islamic suburbs, I’ll point out), is nothing more than a tax on bad protocol design. For the most part it doesn’t create any new value. In the end, we’ve got suburban overpaid internet engineers fighting an imaginary, boundless war with disenfranchised suburban Islamic radicals. Who’s crazier?

Lastly, for all of you who think I’m wrong or resist these predictions because you personally “wouldn’t do that” or can produce one counterexample, I ask you: Are you over 35? If so, your visceral opinion may not matter much. I fail this test myself, but I believe my argument is logically sound and is based in the emerging attitudes of young people.

The future will be made by people younger than we, and based on everything I can see, we are on the cusp of a major realignment of attitudes and economics in America.

It won’t be too much longer til active, entrepreneurial creative professionals (black and white) in our cities look at the suburbs (black and white) and decry the entitlement culture of the suburban welfare state.

March 28th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, software, trends

There’s been a lot of speculation about Google’s plans to deploy Gigabit fiberoptic Internet. Where will they deploy? What are the criteria? How many homes will they serve? Will they favor cities, or rural areas?

Your guess is as good as mine. But as a part of the global tech community and as someone who has spent a lot of time at Google and with people from Silicon Valley, these are my guesses about what they might do.

Cities Offer Higher Returns

Cities have the kind of density required to deliver a lower cost-per-home deployment. Less cable, a single point of negotiation and contact, and the ability to deploy using lateral construction from fiber conduits means lower overall costs.

Multi-family housing means more customers per square mile. Baltimore has a city-owned conduit system which can serve over 90% of the area of the city — without requiring the use of poles or negotiating with third party utilities.

Rural Areas Cannot Be Served Profitably

Telephone companies receive funds from the Universal Service Fund to subsidize service in areas that otherwise cannot be profitably served. Google is not subject to the regulatory framework (Communications Acts of 1934 and 1996) that would give it access to USF funds; in fact, it has every incentive to fight to avoid falling under such regulation.

Google is not a charity, it’s not being subsidized by the government, and it is not a monopoly. There is no special reason why Google should care about making services available in rural areas, and there is certainly no profit motive. Rural service requires fuel, vehicles, and people on the ground. Every part of this is expensive; it’s why it loses money and why it has to be subsidized by USF funds.

Google simply has no motive at all to serve rural areas. I’ll eat cat meat if Google selects a rural area for this trial. It just won’t happen.

Tech Is Opinionated

Google has opinions. In the tech world, people take a stand: Google and Apple both expressed strong opinions about how a smartphone ought to operate. Opinionated software is an emerging trend in software tools. Software designers bake their opinions into the tools they create. People who use those tools end up adopting those opinions; if they don’t, the tools become counterproductive, and they are better off using different tools.

There is every reason to believe that Google’s opinion is that the suburbs are obsolete, and that that opinion will inform their strategy for building out a fiber network. Here’s why Google likely believes the suburbs are obsolete:

- Suburbs rely on car culture, which consumes time; that’s time that people can’t spend on the Internet, making money for Google.

- Suburbs are not energy efficient, requiring lifestyles that generate more CO2 emissions. Google has said it wants to see greater energy efficiency in America.

- Google CEO Eric Schmidt has said he wants to see America close its innovation deficit. There’s nothing innovative about the design of the suburbs. It’s a tired model.

- Schmidt has supported Al Gore politically and in his efforts to combat global warming. Regardless of what you might think of Al Gore or global warming, we have a pretty good idea what Google thinks of the issue.

- Gigabit Fiber in cities could utterly revitalize them. We’ve been looking for ways to fix our cities for the last 50 years. The last renaissance was powered by large-scale economics; a new renaissance can be launched with large-scale communications investment.

- Google’s employees are young, idealistic, and believe in self-powered transportation. It’s worth pointing out that the Google Fiber project lead, Minnie Ingersoll, is an avid cyclist.

The Suburbs Are Done

I’ve said it before. So have others. But I’m not promoting that they be subject to some kind of post-apocalyptic ghettoization, either, so calm down. No one’s threatening your commute or your backyard barbecue.

But what I am saying is that at some point we need to take a stand about where we’re going to invest in our future. About where we believe we can regain competitive advantage and efficiency.

I believe our only hope to do that is with smart, well-designed urban cores, connected with world-class communications infrastructure and fast, green, and efficient people-powered transportation. And I think Google believes that too. Bet on it.

March 2nd, 2010 — art, baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, trends

Google CEO Eric Schmidt recently outlined a case arguing that America needs to address its ongoing “innovation deficit” and spur entrepreneurship and creativity in meaningful new ways.

How did we get here? Why is it that America has an innovation deficit? It’s simple: we have lulled ourselves into complacency. America is bored because we have made ourselves boring.

Unleashing Self-Actualization

What do we mean when we talk about innovation and creativity? Really what we’re talking about is what psychologists call self-actualization. Put simply, it’s nothing more than realizing all of your unique capacities and putting them to good use. Self-actualization occurs best when it’s in the company of others who are doing the same. Companies that achieve remarkable results are typically loaded with people who are either self-actualizing or on a pathway towards it.

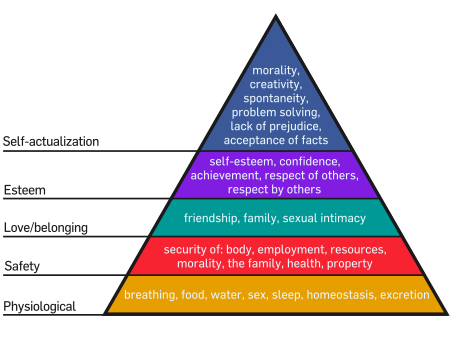

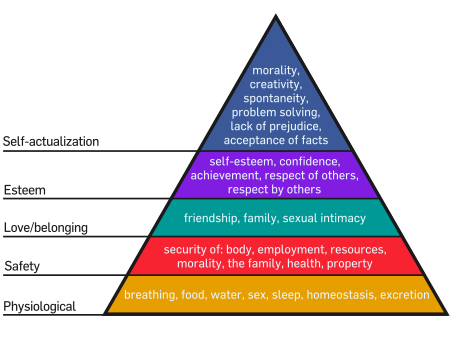

Abraham Maslow described this pathway as the “hierarchy of needs” to highlight the fact that people cannot become fully self-actualized if they are concerned with other more basic needs like food and security.

Like the USDA food pyramid, Maslow’s hierarchy identifies some important elements, but the idea that there is a strictly linear progression towards self-actualization, or that it is inclined to occur naturally, is probably wrong. Looking at the world around us, it’s easy to see examples of people whose lives who have petered out somewhere in the middle of his pyramid, even though their baser needs have been met.

I believe this is because we have designed 21st century America in such a way that we short-circuit the process of self-actualization in a number of important ways.

Problem 1: Suburbs

Self-actualization occurs best when people are able to connect face-to-face to discuss real-world ideas, try things out, and play. This means intellectual conversation with a diverse range of people, including a broad range of views. It means exposure to the arts, to music, and a shared desire to solve meaningful problems.

Suburbs short-circuit these important pathways for self-actualization in these important ways:

- Slowing movement: people are dispersed – gathering requires use of cars

- Lack of diversity: suburbs tend towards less diversity of views, not more

- Diverts self-actualizing motivation into materialistic and trivial pursuits

The first two points are obvious enough, but let’s spend a moment on the last one.

Suburbs divert self-actualization into pursuits like neighborhood-hopping and home improvement. It’s not surprising that we just suffered the effects of a housing bubble. With millions of peoples’ self-actualizing efforts poured into drywall and granite countertops, there was simply a limit to how much housing and home-flipping we can endure. It doesn’t do anything. Working on housing is first-order toiling, not long-term advancement.

Is it surprising that the icons of the housing bubble years were “Home Improvement,” “Home Depot,” and the SUV? The SUV was literally a vehicle for improperly diverted self-actualization: if I have a vehicle that lets me improve my basement and my backyard, I can become the person I want to be.

Problem 2: Artificial Scarcity of Opportunity

Suburbs have had other unfortunate side-effects: we have allowed corporations to define the concept of work. By dispersing into our insulated suburban bubbles, we have largely shut down the innovative engines of entrepreneurship that used to define America. Where we might fifty years ago have been a nation of small businesses and independent enterprises, we are more and more becoming reliant on corporations to tell us what a “job” is and what it is not.

To the extent that we are not spending time together coming up with new important ideas, we are shutting down opportunities for ourselves. And corporations are happy to reinforce and capitalize on this trend. Opportunity is unlimited for people who are legitimately on a pathway towards self-actualization. We choose not to see it because we think of “jobs” as something that can only be provided by “companies,” and not created from scratch by collaboration.

Problem 3: Reality Television

Reality television is an ersatz reality to replace our own. It steps in where we’ve failed at self-actualization. It is both a symptom and a cause of our failure. As a symptom, it shows that we have so much time on our hands that we can spend it worrying about somebody else’s ridiculous “reality.” As a cause, this obsession can only be serviced at the expense of our own shared reality.

Problem 4: Car Culture

As a society, we spend way too much time in cars. Some of this is due to the issues I already raised about suburban design. But besides that, we spend a ridiculous amount of time stuck in traffic, waiting at red lights, and trekking around our metropolises.

Cars are fundamentally isolating. Time spent in a car is time you can’t spend doing something else. Sure, they can be useful, and I’m not anti-car, I’m just anti-stupid. If we as a society are burning many millions of hours each week in our cars stuck in traffic and covering unnecessary miles, it’s hard to see how that’s helping us become self-actualized (unless it’s in the backseat) and become more innovative. It’s a tax on our time.

Some have also suggested that one reason we have so many prohibitions on what we can do while driving is because we really just don’t like driving that much. Maybe the problem with “texting while driving” is that we are driving, not that we are texting. Maybe communication is more important societally than piloting an autonomous 3,000 pound chunk of metal and plastic?

A Solution: Well-Designed Cities

We’ve had the solution under our noses all along, but we’ve chosen to let our cities languish. Historical facts about America have led our cities to evolve in particular ways that differentiate them from some of our peers in Europe in Asia. But there is hope, and we must recognize the assets at hand in our cities.

Cities offer higher density populations which lead in turn to innovation and a flourishing of the arts. They lead to efficiency of movement and face-to-face communication, which is absolutely essential for intellectual self-actualization and entrepreneurship. Well designed public places let people interact and share, and also provide a platform for festivals, celebrations, and entrepreneurship. There are simply too many positive assets to ignore.

Arguments that American cities are unlivable today are tautological and self-reinforcing. The very problems that are most often cited (crime and education) are the same problems that would most benefit from entrepreneurship and real long-term economic development activity.

The root cause for the abandonment of our cities is race. In the case of Baltimore, WASPs left when Jews became concentrated in particular areas. Jews left when blacks became concentrated in particular areas. And “blockbusters” capitalized on the fear by benefiting on both ends of these transactions. In 50 years, Baltimore (and many American cities) changed dramatically.

Young adults today simply do not remember the waves of fear that sparked this initial migration. It may be a stretch to say that we are entering into a “color blind age,” but we do live in an era where we elected the first black president. I believe we are at the very least entering an age where people are willing to consider the American city with fresh eyes.

We are at a turning point, on the cusp of a moment when people will start looking at our cities entrepreneurially, for the assets they possess rather than the history that has defeated them. We are at a point where we can forget the divisive memories of the mid-twentieth century and forge a future in our cities that is based on shared values of self-reliance, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

Designing Our Future

The design constraints we have proposed for the last 50 years — abandoning our cities, relying on cars, building suburbs and big box stores — have led to the America we see today. And I ask simply, “Do you like what you see?”

We’ve let the culture wars frame these difficult design problems for too long, and it’s time now to put them behind us and start to ask questions in fresh terms. It’s clear now the answer likely doesn’t involve old-school silver-bullets like “Public Transportation,” because simply overlaying transport onto a broken suburban design doesn’t fix anything. Building workable cities and investing in long term transportation initiatives that help reinforce a strong urban design is much more sensible.

And make no mistake: self-actualization is an intellectual pursuit, and the kinds of cities that promote real self-actualization, innovation, and entrepreneurship must become hotbeds of intellectual dialog. Truth and acceptance of facts is an underlying requirement for self-actualization, and we can no longer delude ourselves into thinking that a society built on suburban corporate car-culture makes economic sense.

To continue to do so is to prolong and widen America’s innovation deficit.

July 1st, 2009 — baltimore, design, economics, geography, politics, travel, trends

Approaching Baltimore by train from the north, as thousands do each day, a story unfolds.

You see the lone First Mariner tower off in the distance of Canton, and the new Legg Mason building unfolding in Harbor East.

Quickly, you are in the depths of northeast Baltimore. You see the iconic Johns Hopkins logo emblazoned on what appears to be a citadel of institutional hegemony. It is a sprawling campus of unknown purpose, insulated from the decay that surrounds it.

Your eyes are caught by some rowhouses that are burned out. Then some more: rowhouses you can see through front to back. Rowhouses that look like they are slowly melting. Rowhouses with junk, antennas, laundry, piles of God-knows-what out back. Not good. Scary, in fact. Ugly, at least.

Then a recent-ish sign proclaimig “The *New* East Baltimore.” Visitors are shocked to see that the great Johns Hopkins (whatever it all is, they’ve just heard of it and don’t know the University and the Hospital are not colocated) is surrounded by such obvious blight.

Viewers are then thrust into the Pennsylvania Railroad Tunnel where they fester, shell-shocked for two minutes while they gather their bags to disembark at Penn Station, wondering if the city they are about to embark into will be the hell for which they just saw the trailer.

Appearances matter. Impressions matter. One task that social entrepreneurs could take on to improve the perception (and the reality) of Baltimore would be simply this: make Baltimore look better from the train.

We know that the reality of Baltimore is rich, complex, historic, beautiful and hopeful. We ought to use the power of aesthetics and design to help the rest of the world begin to see the better parts of the city we love.

Author’s Note: my father-in-law Colby Rucker was the one that first pointed out to me how awful Baltimore looks from the train. It was on a train trip from New York to Baltimore today that I was inspired to jot down this thought.

If you would like to read a good book about how places can make you feel and convey important impressions, read The Experience of Place (1991) by Tony Hiss (son of the controversial Alger Hiss). They were both Baltimoreans.