February 17th, 2010 — design, economics, philosophy, politics

Despite all the talk of Government 2.0 and transparency, is it really possible to change the current system from within to tackle the challenges of our day? Perhaps not. One leading expert has expressed serious doubts.

We can succeed only by concert. It is not “can any of us imagine better?” but, “can we all do better?” The dogmas of the quiet past, are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty, and we must rise — with the occasion. As our case is new, so we must think anew, and act anew. We must disenthrall ourselves, and then we shall save our country. – Abraham Lincoln, Address to Congress, December 1862

Why is it that we seem completely ill-equipped to handle the central issues of our time? I believe it is because we misunderstand the nature of design and execution and in important, tangible ways we have abandoned design in favor of only execution. This has removed an important weapon from our arsenal, and it is unclear that we can afford to live in our world without it.

Design vs. Execution

What do I mean by Design (big D) in the context of government? The founding fathers were designers. They set out to imagine a governmental mechanism that would outlive them and ensure the core values that they held dear. So, in a real sense the American constitution (and all such similar instruments) is a design object, and executing against it produces a variety of effects. Most of these effects are positive (free speech, equal protection, etc), while some are negative (a silly disproportionate influence of corporations in politics, corporate personhood).

Execution, by contrast, is the everyday operating of the governmental machine as it was designed. This includes the daily activity of Congress, the White House, the Supreme Court, and the like. Sometimes these entities engage in design behavior (making laws, interpreting them, creating policy, setting precedent by imprisoning people without trial) but mostly they do the quotidian business of government: services, revenue collection, law enforcement.

Our government is now 234 years old. Is it possibly time to reconsider some of its basic precepts? Could we possibly engage in new, first-principles design work that would alleviate some of the most undesirable effects of our system?

Arguments Against New Design Activity

James Fallows in a recent article in The Atlantic suggests that the cumulative corrosion of so many special interests on the machine of government has brought it to a standstill. He suggests that it may be time for something like a new Constitutional Convention, but points out that any attempt to conduct such a convention would be a freak-show of unprecedented proportion, and he’s probably right. If you think the special interests are bad now, wait til you give them an opportunity to participate in a founding document!

In the state of Maryland, every 20 years we have the opportunity to vote to have a constitutional convention. This year is one of those years. But while some are calling for such a convention, most politicians consider it “an exercise in futility,” citing cost as the key factor. Why cost? Because so many people would need to be involved.

But this is surely a bad state of affairs. The Maryland constitution is huge, much bigger than the US Constitution, a burden on everyone that has to execute against it, and loaded with unintended effects. Yet, the critics are probably right: if we approach our design activities with the same appeal to the lowest common denominator as we have our execution activity, a new design would be a circus.

Fallows and Maryland Senate President Mike Miller both suggest that we plod along with our broken foundations because it is the only moral thing to do and even though we may have a tough time executing our way out of our design shortcomings.

Gaining Clarity About Design vs. Execution

A few days ago I wrote a blog post about how our educational system is broken, and at the end I cited several bullet points suggesting “core values” for the design of a new system.

Several people shot back in the comments with ways in which the current system does embrace some of the core values that I suggested, at least some of the time.

And it has struck me: we’re talking about two different things. I was talking about a new, imagined design. Some people thought I was talking about how the current system needed to change its execution. Those are two very different things and it began to dawn on me: our historic aversion to new design activity has caused us to push Design Thinking out of our political debate entirely.

Today, all political debate is around execution (activity) and not design (legacy).

We Must Disenthrall Ourselves

Lincoln said it best in 1862. We must disenthrall ourselves; disenthrall ourselves with the strengths of our system’s design, and disenthrall ourselves with the notions of the past. In order to move past where we are, we need to engage in new, imaginative design thinking and do something with it.

While new constitutional conventions are probably not the most productive approach, we must make ourselves open again to talking about design activity and understand the difference between execution and design. We must try to understand how we can conduct design activity through execution of our current system, and we must gain clarity about the limits of that prospect.

It is entirely possible that we cannot meaningfully affect the design of our system by execution alone; we may need to appoint some Great People to revise our system in a way that we all can live with. While this is a frightening thought when considered from inside the confines of our current government, it may well be necessary.

Jefferson anticipated this conundrum and believed occasional revolution would be necessary. Can we prove that we’ve learned something from his design and rise to the challenge of repairing it without bloodshed?

Thanks to Sir Ken Robinson, from whom I stole this very apropos Lincoln quote which he cited in his recent talk at TED 2010.

February 16th, 2010 — business, design, economics, philosophy, trends

In my recent post on Effectuation, I highlighted the work of Dr. Saras Sarasvathy, who coined the term.

One of the points she makes in her book is that entrepreneurship is a branch of design thinking. This is an absolutely brilliant insight.

First, if you are the sort who thinks that design is a discipline centered around making chairs, teapots, web pages, or books, you should read up on the topic (see below). Design is a pattern for thinking, and while design thinking often produces the “beautiful things” which we have traditionally associated with design, widespread application of design thinking is beginning to have far-reaching effects on our society.

Design thinking starts with a simple grab-bag of elements: one or more goals, and one or more constraints. Constraints might be size, cost, weight, and psychological properties of the user. Goals might be to solve a particular problem or to make money. It is then the designer’s job to propose a solution that carefully considers the effects of the available solutions to propose the best possible, most beautiful and simplest solution.

What do I mean by the effects of a solution? If you follow popular mathematics at all, you might be familiar with the work of Benoit Mandelbrot, who suggests that reality is fractal and folds in on itself to produce patterns of amazing complexity from simple constraints. Mandelbrot’s formulae are a kind of simple design constraint that produce patterns of stunning complexity.

Similarly, designers can create complex patterns on the world by building systems or objects that include very simple design constraints. We see examples of these effects every day: the poorly designed chair that pulls apart its base after a bit of use, or the well-placed door handle that gets shinier and more beautiful with every use.

But these are just objects. What about systems and institutions like the United States government or the American public school system? The US Constitution is a piece of design, as are the laws that built our school system. The effects that those designs are now producing are sometimes more corrosive than their designers would ever have imagined. Both of those institutions are in need of “design refreshes” to clear away unintended corrosive effects.

Entrepeneurship and Design

Sarasvathy suggests that in the process of effectuation, the entrepreneur first makes an assessment of what assets and connections are available to them and then asks the simple question, “What can I do with it?”

At this moment, the entrepreneur becomes a designer. They are looking at what they have as design constraints and trying to move themselves closer to their goals. Sarasvathy makes a key additional insight; after the first round, the entrepreneur asks, “What else can I do with it?”

This puts the entrepreneur into the position of being a broad-based free-thinker, going beyond the simple condition of “how do I work within these constraints to achieve a goal,” but instead towards the question “what is the set of goals that I can achieve elegantly within these constraints?” This is a powerful inversion and is one that gives an imaginative entrepreneur an amazing power to transform society.

And here is a key point of difference between society’s conception of designers and entrepreneurs, even though they effectively perform much of the same kind of thinking: a designer is typically handed constraints and goals and asked to produce a product. An entrepreneur is issued constraints (the context of their life situation) without specific goals and rises to the opportunity to choose both the goals and the path.

I sometimes get frustrated with “designers and architects” because they cannot think of their own work outside of the context of their clients. They blame their own inability to do great work on the lack of vision of their clients, and I have to say I am apathetic to that line of thinking. It is time that designers and architects throw off the shackles of their clients and become entrepreneurs themselves. Show us what you believe, not what you can be paid to do.

Great entrepreneurs have been finding ways to finance their own design thinking for eons. It’s time that businesspeople start understanding that they are designers, and it’s way past time for the greatest designers to become their own clients and produce the great work they are called to create.

Some Suggested Reading

November 7th, 2009 — art, baltimore, business, design, geography, philosophy, trends

In 1983 at age 12, I became drawn to the design and tech culture of San Francisco. By that time I was already deeply involved in computers and the other tech of the day, and had been reading every issue of BYTE Magazine cover-to-cover when it arrived in our mailbox after school.

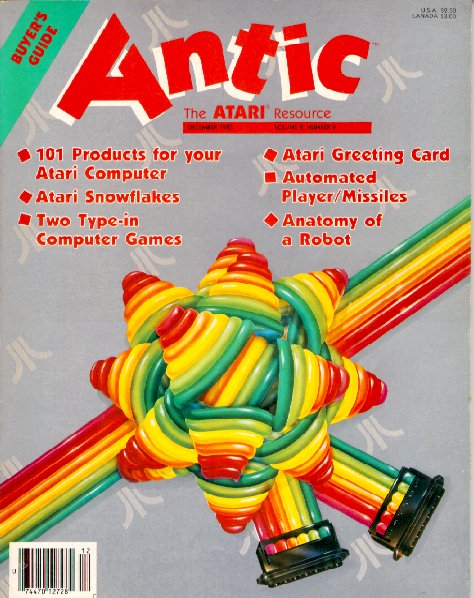

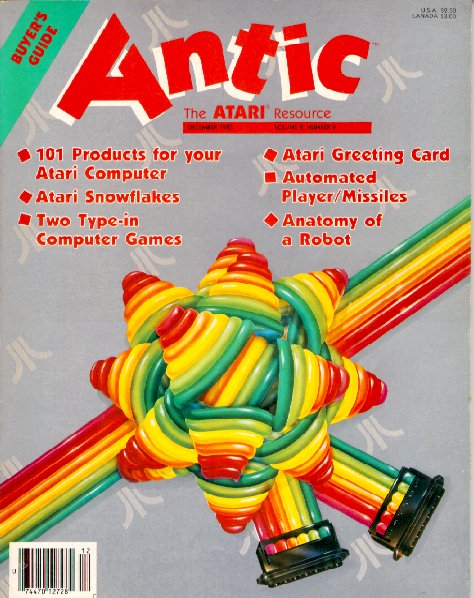

BYTE was produced in New Hampshire and had a scholarly tone; still, the emerging world of computing was breathlessly covered, and offered a sense of endless possibility. But it was Antic magazine (a specialty computing magazine for Atari computers), specifically the December 1983 “Buyer’s Guide” issue that really caught my eye.

The design was colorful and imaginative, with beautiful typography, and the magazine was full of amazing ideas and products which I was sure would launch me on my way to unlimited exploration. I devoured the magazine cover to cover, but I never realized just how much I was soaking up its design ethos. Colorful, playful, and bold, this was not the wry, academic BYTE. It was combining the substance of tech with the emerging design scene in San Francisco, and it resonated with me profoundly.

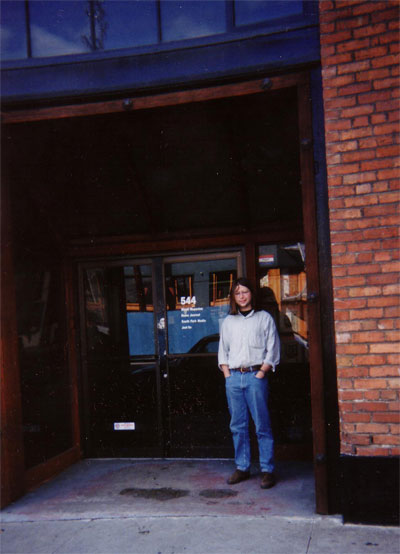

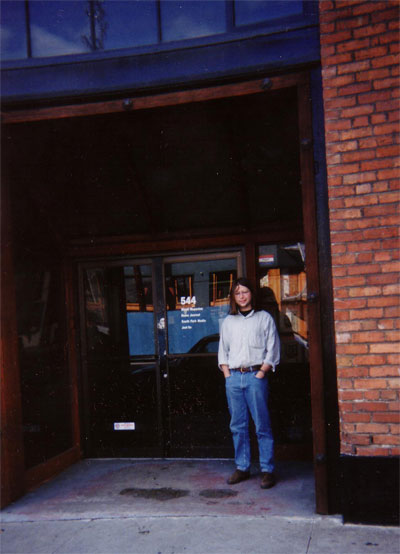

In 1985, I got a job at a local computer store doing what I loved: selling computers and software and, yes, copies of Antic magazine. In 1986, I started my own computer and software sales company, Toad Computers. In 1989, months after graduating from high school, I had the chance to visit Antic Magazine — this time as an advertiser.

This was my first trip to San Francisco and I visited Antic at their loft office, located at 544 Second Street, right in the heart of the city’s SOMA district. But this was SOMA before it was the SOMA we know now as the home of so many startup tech companies. Beat up and edgy, the open-air second floor office had high-beamed ceilings and gave a sense of history and limitless potential. I was smitten with the city and with valley tech culture – I also visited Atari’s headquarters in Sunnyvale that trip – and absorbed all that I saw.

Later in 1993, I was twenty-one and searching for new things to explore. Toad Computers was doing well but I knew that it would have to change and grow to survive. Atari was having tough times. Antic magazine had folded. To advertise effectively we were sending out massive catalog mailings, featuring 56 page catalogs that I personally designed – very much in the visual style of Antic magazine.

Someone had told me about a new magazine called Wired. I picked up a copy and was immediately struck with its sense of visual design and its aura of infinite possibility through the combination of design and tech. Again, I ingested every word, photo, and illustration in each issue. In early 1994, I noticed an ad that indicated that Wired – this tiny publishing startup – was looking for a circulation manager. I was entranced at the possibility. With my background in direct marketing and managing big catalog mailing lists, I thought this might be an opportunity for me.

In February 1994, I booked a trip to San Francisco to talk to my kindred spirits at Wired about the possibility of working there. I also became entranced with the Internet and its possibilities at this time, and for several days before my trip to San Francisco, I worked feverishly to write an article for Wired about how the Internet – when it became fully developed and evolved – could become a kind of real-time Jungian web of knowledge that acted like a global brain cheap kamagra oral jelly uk. I theorized that the Internet could become a kind of collective consciousness that enabled humanity’s genius to be available to everyone all the time. I predicted online banking, shopping, and video chat and made illustrations to show how these things would work.

Me, with long hair, at Wired HQ in February 1994

Of course, the simple things were not hard to predict at that time, though they were still a few years off. But my central thesis about Jungian synchronicity was just too wacko to print in 1994. And to be fair, I had cobbled the article together in just a couple of days, had worked in ample quotes from Marshall McLuhan and Carl Jung, and had interviewed no one. My thesis may have been strong, but the piece would have benefited from some interviews and editing. But hey, I was inspired and twenty-two.

When I went to Wired’s offices, I was stunned to learn that they were located in the same office that Antic had occupied! The same open air loft office at 544 Second Street. I met with some folks from Wired’s barebones staff. I commented on my perceived sense of Jungian synchronicity — about Antic and Wired sharing the same office space. We talked about job possibilities. I submitted my article.

I didn’t get a job, and they didn’t print my article. To be fair, I wasn’t really ready to move to San Francisco, and I am sure they sensed that. I also wasn’t sure what I wanted. I just knew that I was drawn to this hopeful admixture of design and tech that seemed to emanate, radio-like, from 544 Second St.

In March 2007, two weeks after I had built Twittervision and a week after SXSW launched Twitter onto the early adopter stage, I thought it would be fun to stop by Twitter HQ in San Francisco. I met Biz and Jack and Ev, and was once again amazed to see that something I had been drawn to had come from SOMA; just a few blocks from 544 Second St. And ironically, it is now Twitter and the “Real Time Web” that is beginning to enable the kind of global consciousness that I had predicted in 1994.

This past Thursday at TEDxMidAtlantic (of which I was the lead organizer and curator) in Baltimore, I was struck by the beautiful design of our stage set. (Thanks to Paul Wolman at Feats, Inc. for bringing it together for us!) A simple combination of bookshelves, cut lettering, books, a few objects and blue wash backlighting had combined to produce a gorgeous backdrop for the extraordinary ideas that our speakers would soon be sharing. And I felt at home. I could not go to 544 Second Street and SOMA. Instead, it was my mission to bring it here.

July 1st, 2009 — baltimore, design, economics, geography, politics, travel, trends

Approaching Baltimore by train from the north, as thousands do each day, a story unfolds.

You see the lone First Mariner tower off in the distance of Canton, and the new Legg Mason building unfolding in Harbor East.

Quickly, you are in the depths of northeast Baltimore. You see the iconic Johns Hopkins logo emblazoned on what appears to be a citadel of institutional hegemony. It is a sprawling campus of unknown purpose, insulated from the decay that surrounds it.

Your eyes are caught by some rowhouses that are burned out. Then some more: rowhouses you can see through front to back. Rowhouses that look like they are slowly melting. Rowhouses with junk, antennas, laundry, piles of God-knows-what out back. Not good. Scary, in fact. Ugly, at least.

Then a recent-ish sign proclaimig “The *New* East Baltimore.” Visitors are shocked to see that the great Johns Hopkins (whatever it all is, they’ve just heard of it and don’t know the University and the Hospital are not colocated) is surrounded by such obvious blight.

Viewers are then thrust into the Pennsylvania Railroad Tunnel where they fester, shell-shocked for two minutes while they gather their bags to disembark at Penn Station, wondering if the city they are about to embark into will be the hell for which they just saw the trailer.

Appearances matter. Impressions matter. One task that social entrepreneurs could take on to improve the perception (and the reality) of Baltimore would be simply this: make Baltimore look better from the train.

We know that the reality of Baltimore is rich, complex, historic, beautiful and hopeful. We ought to use the power of aesthetics and design to help the rest of the world begin to see the better parts of the city we love.

Author’s Note: my father-in-law Colby Rucker was the one that first pointed out to me how awful Baltimore looks from the train. It was on a train trip from New York to Baltimore today that I was inspired to jot down this thought.

If you would like to read a good book about how places can make you feel and convey important impressions, read The Experience of Place (1991) by Tony Hiss (son of the controversial Alger Hiss). They were both Baltimoreans.