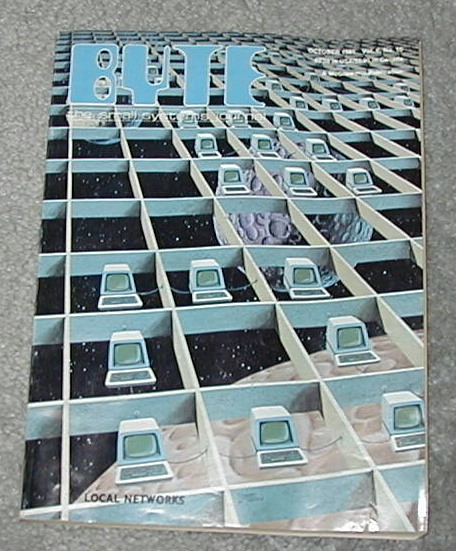

In 1983 at age 12, I became drawn to the design and tech culture of San Francisco. By that time I was already deeply involved in computers and the other tech of the day, and had been reading every issue of BYTE Magazine cover-to-cover when it arrived in our mailbox after school.

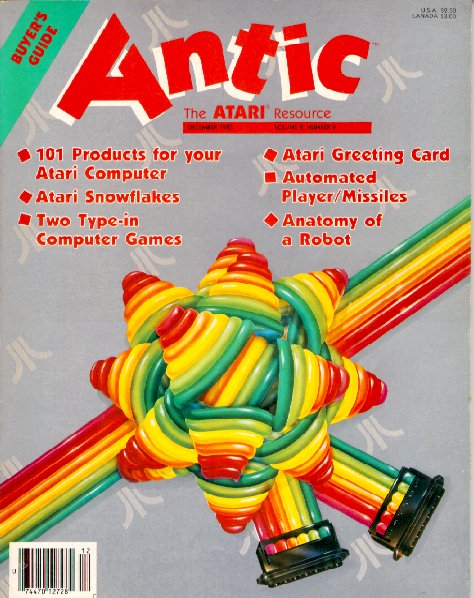

BYTE was produced in New Hampshire and had a scholarly tone; still, the emerging world of computing was breathlessly covered, and offered a sense of endless possibility. But it was Antic magazine (a specialty computing magazine for Atari computers), specifically the December 1983 “Buyer’s Guide” issue that really caught my eye.

The design was colorful and imaginative, with beautiful typography, and the magazine was full of amazing ideas and products which I was sure would launch me on my way to unlimited exploration. I devoured the magazine cover to cover, but I never realized just how much I was soaking up its design ethos. Colorful, playful, and bold, this was not the wry, academic BYTE. It was combining the substance of tech with the emerging design scene in San Francisco, and it resonated with me profoundly.

In 1985, I got a job at a local computer store doing what I loved: selling computers and software and, yes, copies of Antic magazine. In 1986, I started my own computer and software sales company, Toad Computers. In 1989, months after graduating from high school, I had the chance to visit Antic Magazine — this time as an advertiser.

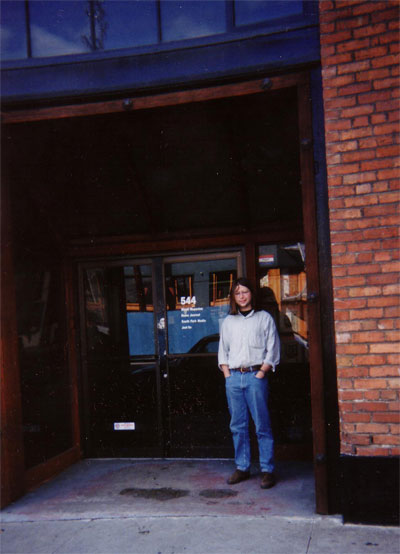

This was my first trip to San Francisco and I visited Antic at their loft office, located at 544 Second Street, right in the heart of the city’s SOMA district. But this was SOMA before it was the SOMA we know now as the home of so many startup tech companies. Beat up and edgy, the open-air second floor office had high-beamed ceilings and gave a sense of history and limitless potential. I was smitten with the city and with valley tech culture – I also visited Atari’s headquarters in Sunnyvale that trip – and absorbed all that I saw.

Later in 1993, I was twenty-one and searching for new things to explore. Toad Computers was doing well but I knew that it would have to change and grow to survive. Atari was having tough times. Antic magazine had folded. To advertise effectively we were sending out massive catalog mailings, featuring 56 page catalogs that I personally designed – very much in the visual style of Antic magazine.

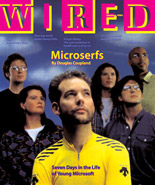

Someone had told me about a new magazine called Wired. I picked up a copy and was immediately struck with its sense of visual design and its aura of infinite possibility through the combination of design and tech. Again, I ingested every word, photo, and illustration in each issue. In early 1994, I noticed an ad that indicated that Wired – this tiny publishing startup – was looking for a circulation manager. I was entranced at the possibility. With my background in direct marketing and managing big catalog mailing lists, I thought this might be an opportunity for me.

In February 1994, I booked a trip to San Francisco to talk to my kindred spirits at Wired about the possibility of working there. I also became entranced with the Internet and its possibilities at this time, and for several days before my trip to San Francisco, I worked feverishly to write an article for Wired about how the Internet – when it became fully developed and evolved – could become a kind of real-time Jungian web of knowledge that acted like a global brain cheap kamagra oral jelly uk. I theorized that the Internet could become a kind of collective consciousness that enabled humanity’s genius to be available to everyone all the time. I predicted online banking, shopping, and video chat and made illustrations to show how these things would work.

Me, with long hair, at Wired HQ in February 1994

Of course, the simple things were not hard to predict at that time, though they were still a few years off. But my central thesis about Jungian synchronicity was just too wacko to print in 1994. And to be fair, I had cobbled the article together in just a couple of days, had worked in ample quotes from Marshall McLuhan and Carl Jung, and had interviewed no one. My thesis may have been strong, but the piece would have benefited from some interviews and editing. But hey, I was inspired and twenty-two.

When I went to Wired’s offices, I was stunned to learn that they were located in the same office that Antic had occupied! The same open air loft office at 544 Second Street. I met with some folks from Wired’s barebones staff. I commented on my perceived sense of Jungian synchronicity — about Antic and Wired sharing the same office space. We talked about job possibilities. I submitted my article.

I didn’t get a job, and they didn’t print my article. To be fair, I wasn’t really ready to move to San Francisco, and I am sure they sensed that. I also wasn’t sure what I wanted. I just knew that I was drawn to this hopeful admixture of design and tech that seemed to emanate, radio-like, from 544 Second St.

In March 2007, two weeks after I had built Twittervision and a week after SXSW launched Twitter onto the early adopter stage, I thought it would be fun to stop by Twitter HQ in San Francisco. I met Biz and Jack and Ev, and was once again amazed to see that something I had been drawn to had come from SOMA; just a few blocks from 544 Second St. And ironically, it is now Twitter and the “Real Time Web” that is beginning to enable the kind of global consciousness that I had predicted in 1994.

This past Thursday at TEDxMidAtlantic (of which I was the lead organizer and curator) in Baltimore, I was struck by the beautiful design of our stage set. (Thanks to Paul Wolman at Feats, Inc. for bringing it together for us!) A simple combination of bookshelves, cut lettering, books, a few objects and blue wash backlighting had combined to produce a gorgeous backdrop for the extraordinary ideas that our speakers would soon be sharing. And I felt at home. I could not go to 544 Second Street and SOMA. Instead, it was my mission to bring it here.