Approaching Baltimore by train from the north, as thousands do each day, a story unfolds.

You see the lone First Mariner tower off in the distance of Canton, and the new Legg Mason building unfolding in Harbor East.

Quickly, you are in the depths of northeast Baltimore. You see the iconic Johns Hopkins logo emblazoned on what appears to be a citadel of institutional hegemony. It is a sprawling campus of unknown purpose, insulated from the decay that surrounds it.

Your eyes are caught by some rowhouses that are burned out. Then some more: rowhouses you can see through front to back. Rowhouses that look like they are slowly melting. Rowhouses with junk, antennas, laundry, piles of God-knows-what out back. Not good. Scary, in fact. Ugly, at least.

Then a recent-ish sign proclaimig “The *New* East Baltimore.” Visitors are shocked to see that the great Johns Hopkins (whatever it all is, they’ve just heard of it and don’t know the University and the Hospital are not colocated) is surrounded by such obvious blight.

Viewers are then thrust into the Pennsylvania Railroad Tunnel where they fester, shell-shocked for two minutes while they gather their bags to disembark at Penn Station, wondering if the city they are about to embark into will be the hell for which they just saw the trailer.

Appearances matter. Impressions matter. One task that social entrepreneurs could take on to improve the perception (and the reality) of Baltimore would be simply this: make Baltimore look better from the train.

We know that the reality of Baltimore is rich, complex, historic, beautiful and hopeful. We ought to use the power of aesthetics and design to help the rest of the world begin to see the better parts of the city we love.

Author’s Note: my father-in-law Colby Rucker was the one that first pointed out to me how awful Baltimore looks from the train. It was on a train trip from New York to Baltimore today that I was inspired to jot down this thought.

If you would like to read a good book about how places can make you feel and convey important impressions, read The Experience of Place (1991) by Tony Hiss (son of the controversial Alger Hiss). They were both Baltimoreans.

I was 5 years old in 1977, and all-in-all, I’d say the aesthetics of the day made a big impression on me. Here are some of the things that, looking back on it 31 years later, seem to share a common visual language and which were most influential on the next 10 years in movies, computing, games, and package design.

The rich colors and ground-breaking special effects of Spielberg’s 1977 Close Encounters of the Third Kind marked the beginning of a new era in filmmaking and ultimately set a goal for computer graphics and video games. The nascent digital graphics industry was barely capable of producing color “high-res” graphics, but folks knew that when they could, these were the kinds of graphic effects they wanted to make.

Maybe it’s just me, but it seems to me that Close Encounters, Atari, Space Invaders, and Star Wars were all linked together with a common visual sense. I think it’s pretty obvious that Atari ripped off Close Encounters for the Space Invaders packaging.

Likewise, the colorful “light organ” used to communicate with the aliens in Close Encounters is a close cousin, visually, to the famous Atari game Breakout. Steve Jobs was one of the designers of the arcade version of Breakout. Note the similarity to the original “rainbow” Apple logo.

Computer-generated music and sound was still in its very earliest stages, but the simple John Williams melody put to such brilliant use in Close Encounters was the sort of musical coda that aspiring game designers and programmers could latch onto and reproduce. John Williams of course scored hit after hit in movie soundtracks, but the Close Encounters and Star Wars themes of 1977 were hugely influential.

Spielberg used the Rockwell International logo (center) to clever aesthetic effect in Close Encounters; contractors at the secret military base at Devil’s Tower sported it, visually quoting the Devil’s Tower landscape. Of course, it’s interesting to note how similar the logos are for Atari, Rockwell, and Motorola – all major corporations of the day.

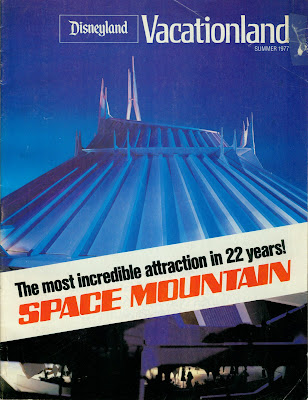

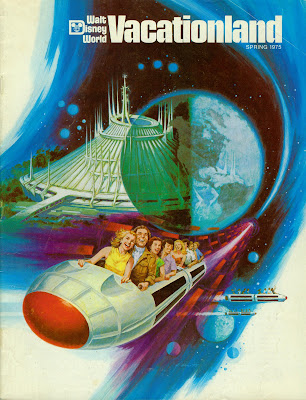

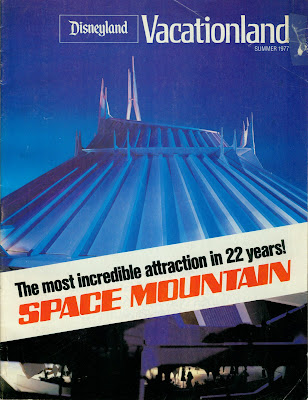

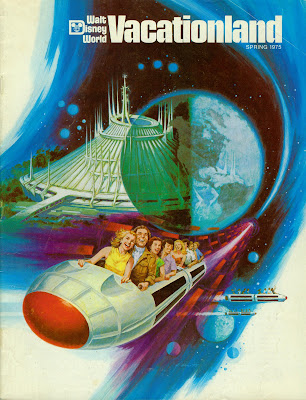

Disney got into the act in 1977 with the opening of Space Mountain. While they may not have been directly influenced by imagery from Close Encounters, Atari, or Star Wars, it’s clear that the popular imagination was drawing from common influences like Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey from 1969.

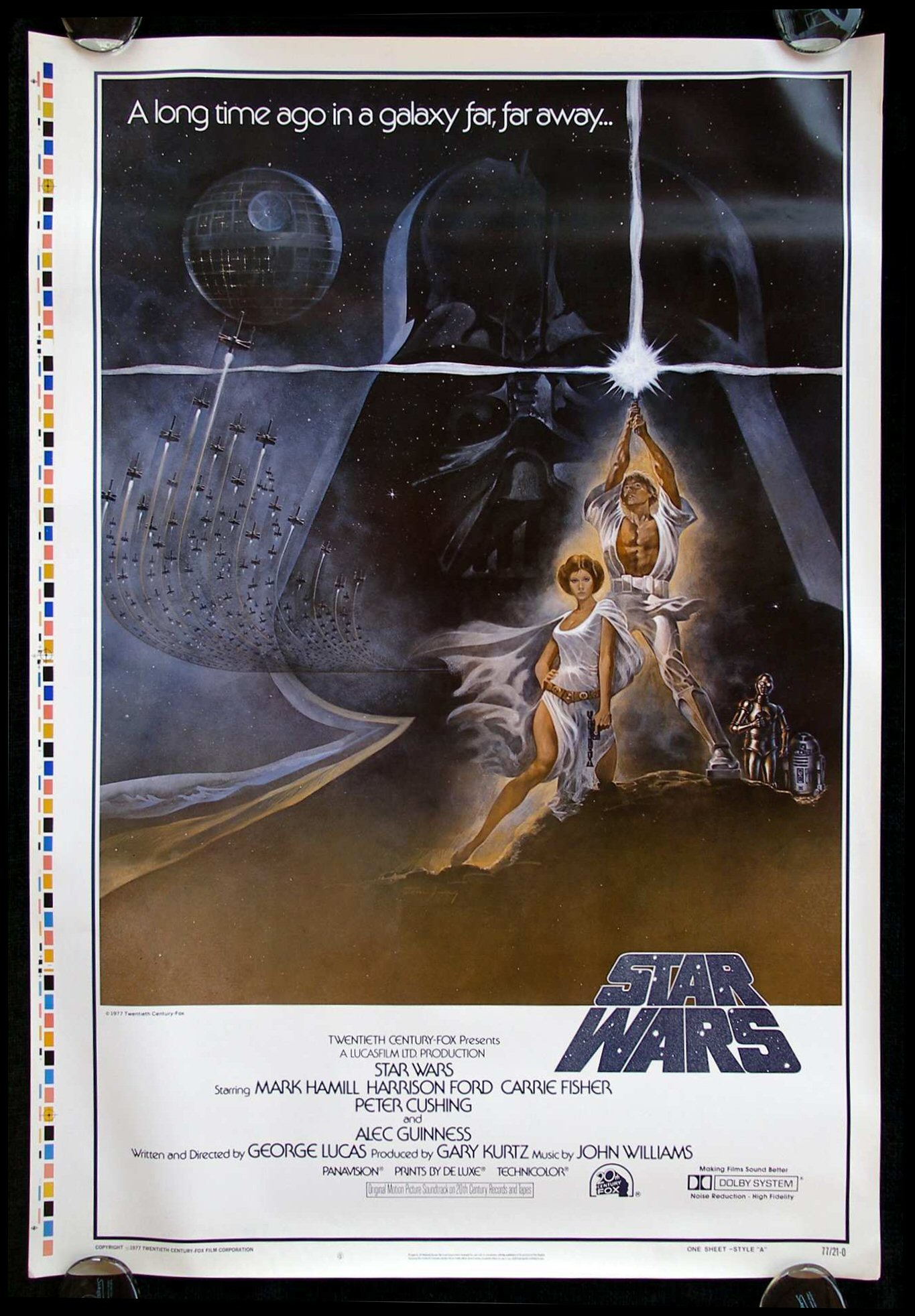

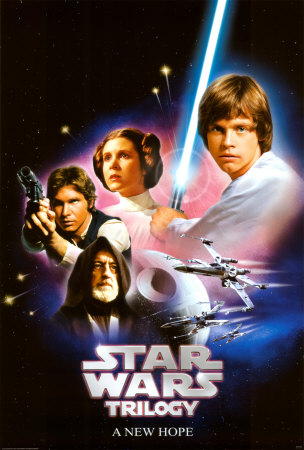

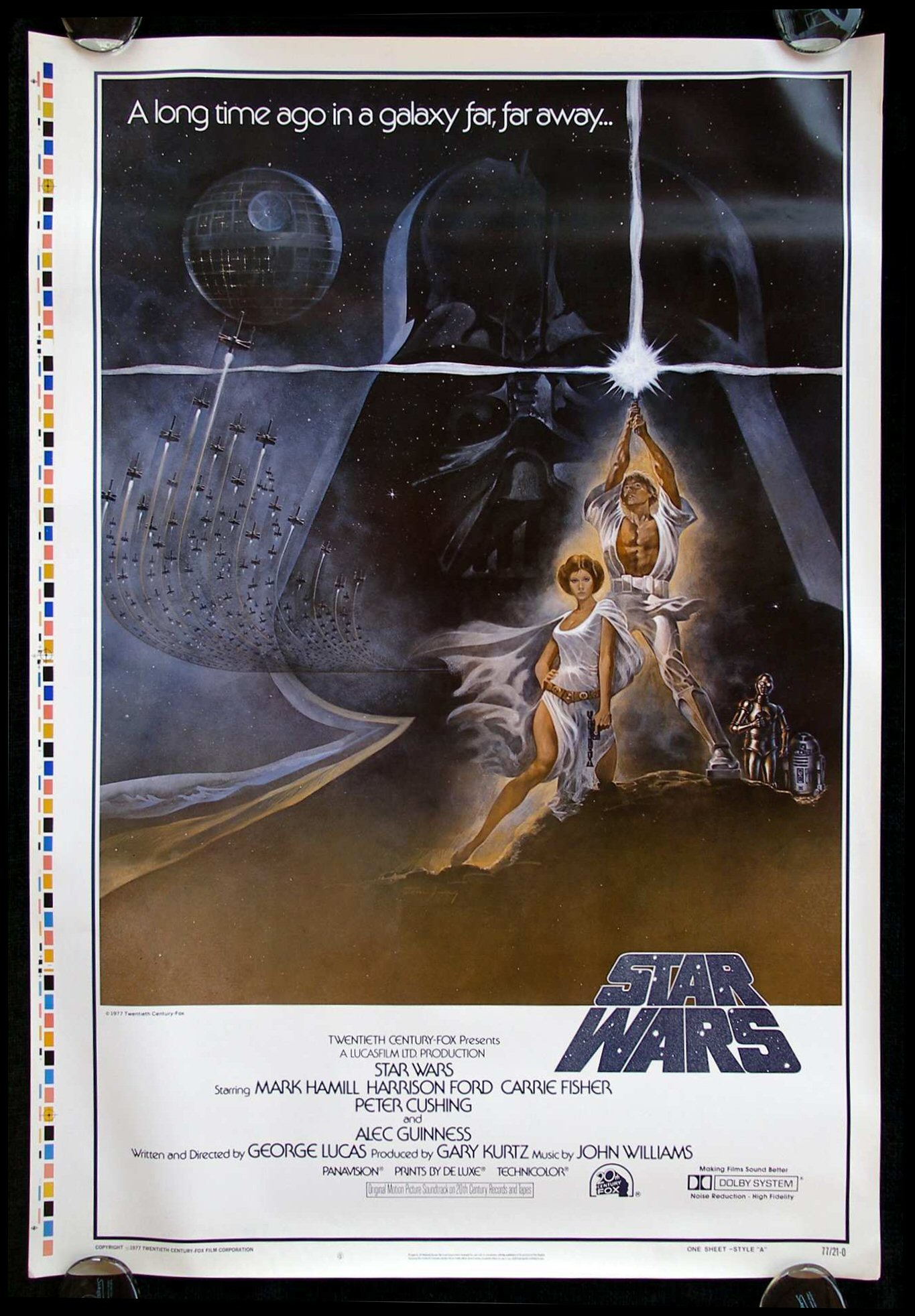

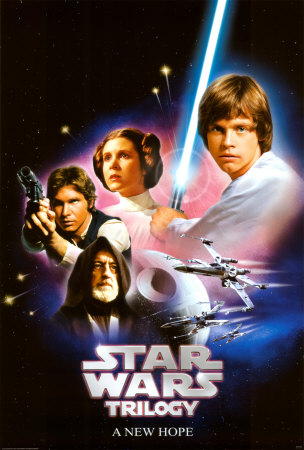

Of course the biggest influence of 1977 was George Lucas’ seminal work, Star Wars, which interestingly was not initially marketed using its iconic title graphics in its movie poster. It took a little while, and for the film to settle into its status as an international blockbuster, for it to adopt the visual marketing language that would become familiar in the release of the subsequent films in the series.

Arguably, the latter sans-serif Star Wars bubble letters were more inline with the iconography of Close Encounters, Atari, and the other major visual influencers of 1977. I’d bet the previous, blockier Star Wars graphic was designed in 1975 or 1976, before the film and its title graphics were completed. And the very earliest Star Wars art from the 1973-1974 timeframe used a hand-drawn serifed font — a different look altogether.

The dirty, realistic “used universe” designed for Star Wars was also influential. Unlike previous science fiction and space films, Lucas imparted his universe with a lived-in, beat-up look that added a romantic touch of decay to an imagined future — or past.

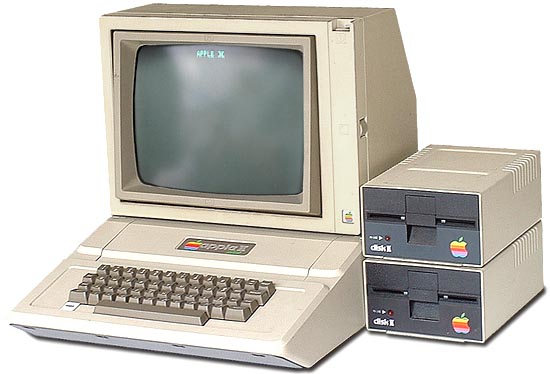

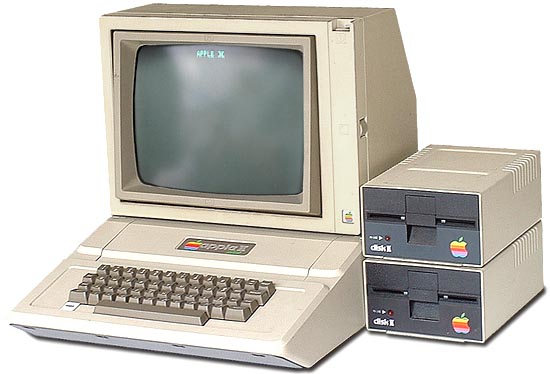

The Apple ][ was a direct result of Jobs’ (and Wozniak’s) work on Breakout, and the color graphics circuitry has much in common. And I don’t think it’s any stretch to say that the generation of Silicon Valley idealists that designed the Apple ][ and Atari 800 were hugely influenced by the blockbuster science fiction films of the day. While the early Apple designs lacked sufficient economy of scale or budget to have a very “designed” aesthetic, the Apple II does look like something straight out of the Star Wars universe. And the ugly Disk ][ and portable monitor are things that just didn’t get attention yet. Maybe they’re dirty, lived-in artifacts of a galaxy far, far away?

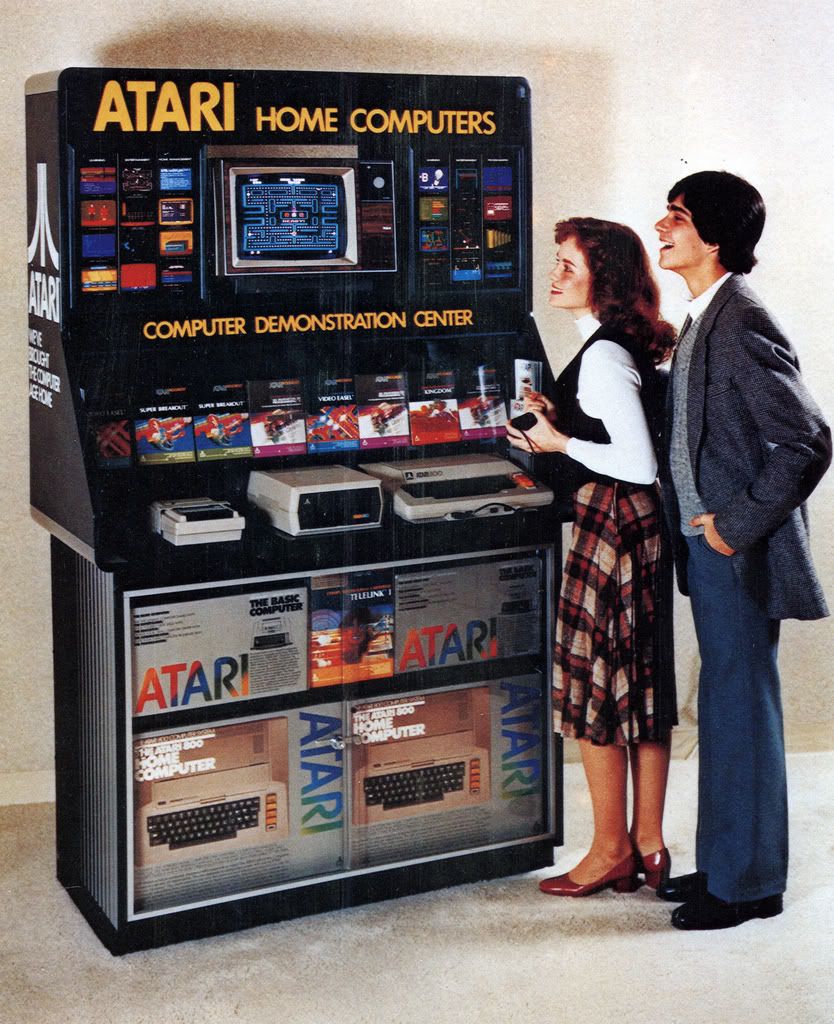

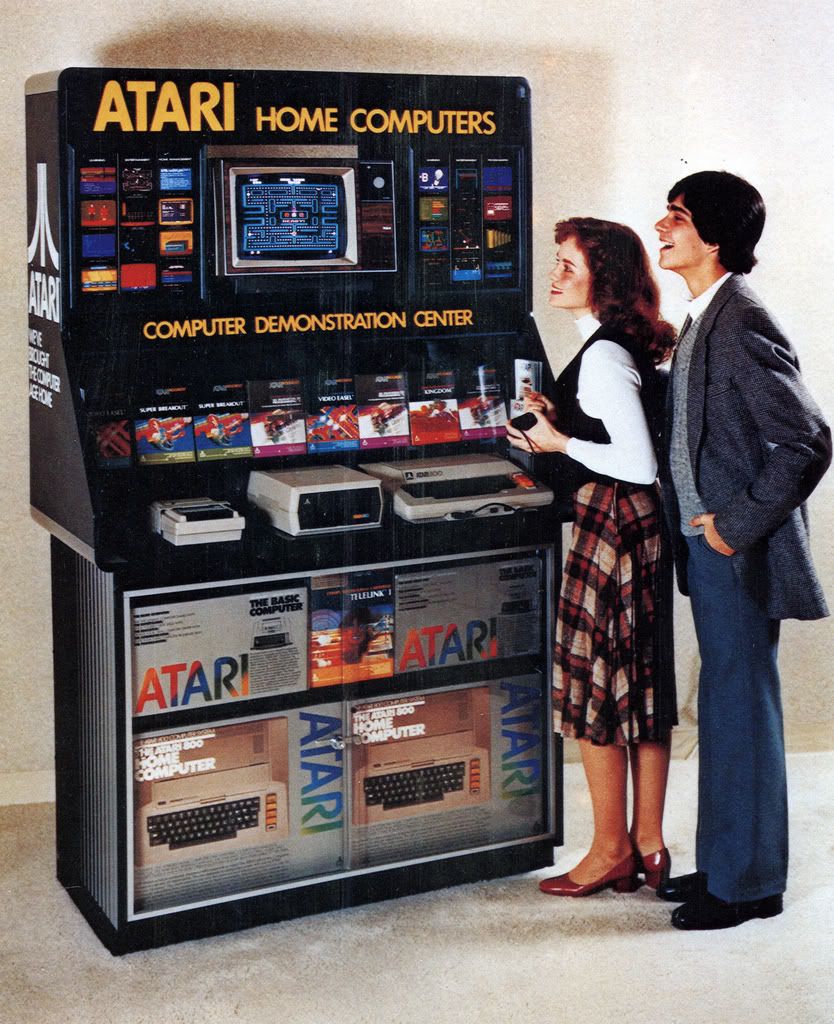

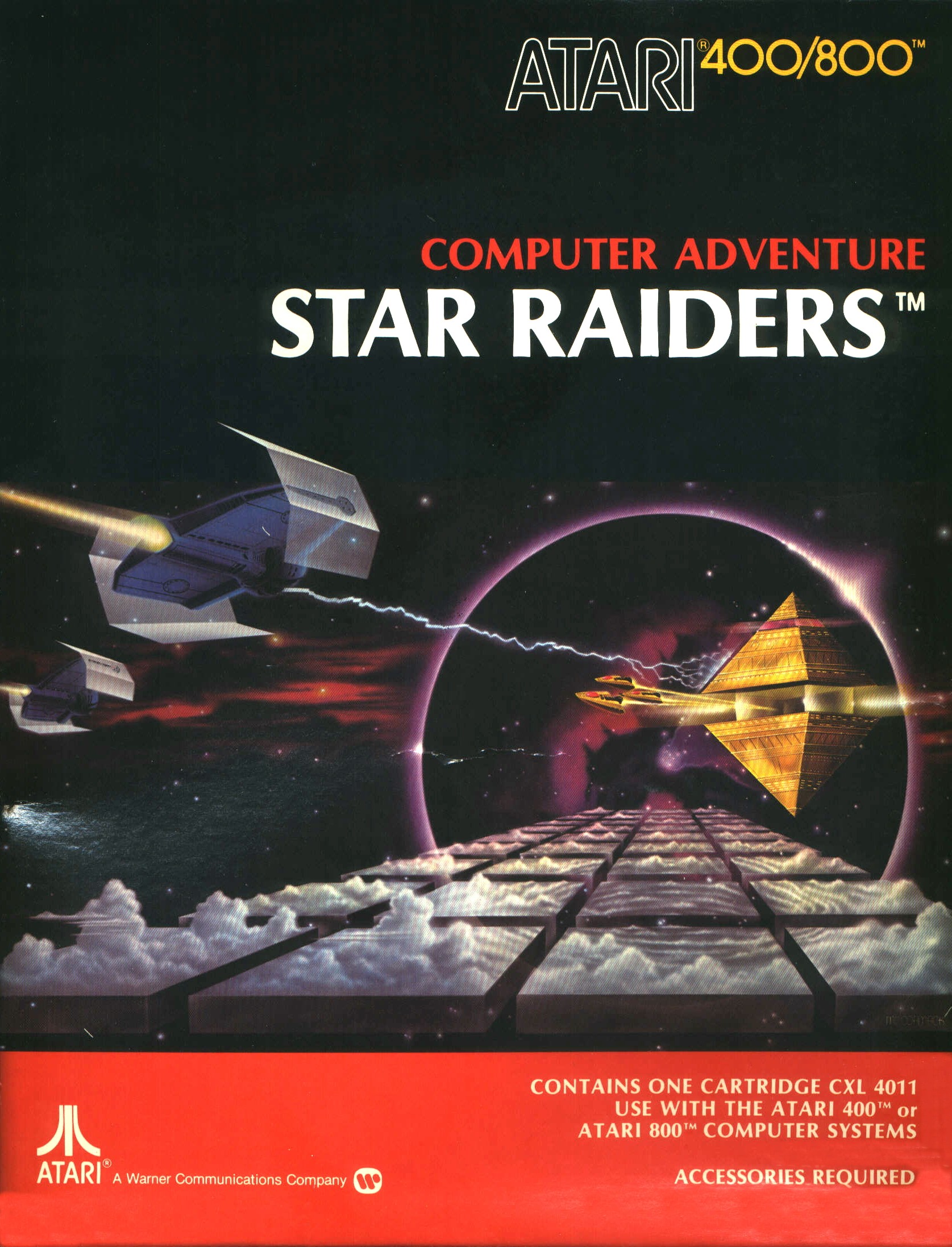

Atari, on the other hand, with the success of the 2600 VCS and its computers, had fully embraced the 1977 aesthetics and by 1980 had full color graphic packaging and a line of “Star Wars” compliant peripherals. And the packaging for the programs borrowed from movie poster designs.

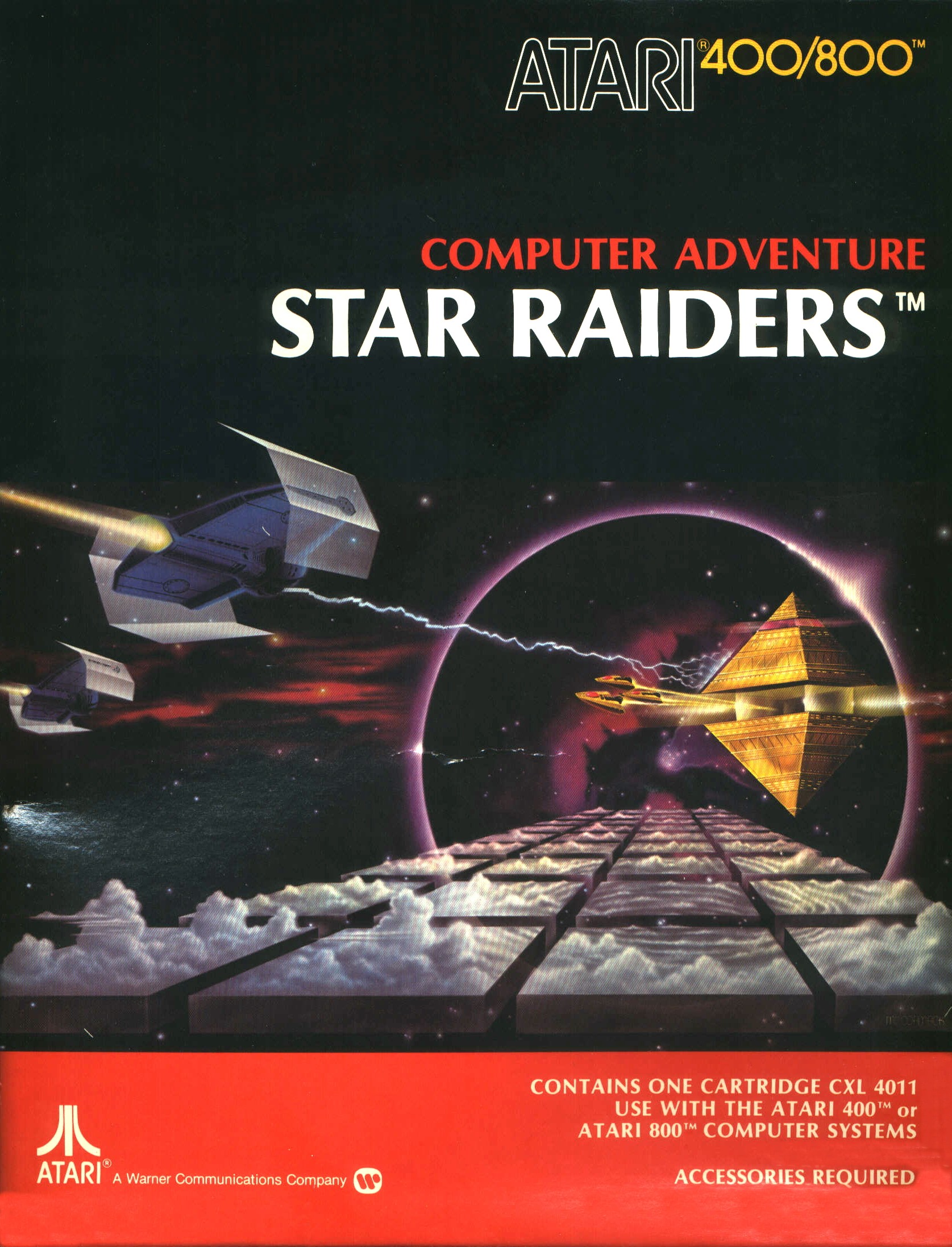

Quite clearly Star Raiders (1979) borrowed directly from Star Wars. In fact, looking at this graphic, I’m now surprised that Atari didn’t get a phone call from Lucas. I guess this was back in the day before tie fighters were Tie FightersTM.

Media critics have argued that Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind marked the start of the era of blockbuster films, and a general shift in popular culture away from smaller, more thoughtful cinema and towards a populist, anti-intellectual approach in art and film in particular.

Whether that’s true or not, I think it is fair to say that 1977 did mark the year of a seismic shift in aesthetics that has been felt all the way through today in computing, gaming, film, and product packaging. Perhaps 1977 is a kind of bright-line marker for popular art — before and after seem to be from entirely different eras.

The fact that I’ve spent most of my life selling products or working in technologies directly influenced by this powerful aesthetic sense is likely no coincidence: to be young in 1977 was to be indelibly marked by the look and feel of a new era.