Entries Tagged 'trends' ↓

June 5th, 2010 — business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, software, travel, trends

Pride, Passion, Talent on Display at Startup Weekend Seoul

I believe that Silicon Valley may soon be going the way of the floppy disk.

For the last two weeks I have been traveling around Asia with a group of tech entrepreneurs, on a trip called “Geeks on a Plane” organized by Silicon Valley investor Dave McClure. I took the same trip last year.

Why take a trip like this? The answer gets at some very real and seismic shifts taking place in the startup world that will be big news over the next few years.

Startups Cost Less

Ten years ago a successful Internet startup might require one to five million dollars in outside funding. Data centers, engineers, and software licenses were hot commodities and could easily drain a startup’s resources.

Now it is possible to get a startup to the point of testing it in the market — with real customers — for $25,000 to $50,000. This effectively removes VC’s from the equation at these early rounds and turns things over to angel investors. As angel investing becomes increasingly professionalized, success rates increase and more people become involved with it.

“Silicon Valley is a State of Mind, Not Necessarily a Real Place”

Pay attention to this one! This is a quote by Dave McClure and it captures what is happening perfectly. Everywhere you go, there are techies and entrepreneurs who follow the tech business scene, and they are all ideological peers.

Silicon Valley is all about embracing the idea that the world can be changed for the better, and that one can (ultimately) realize rewards by changing it. If you believe this, you are a part of Silicon Valley. What about that statement is related to place?

In Shanghai, Beijing, Seoul, Singapore and Tokyo I have seen first hand the buzz and excitement that comes from people who believe that they can engage with the problems of our world imaginatively and productively. And they are not moving to Silicon Valley.

3D Printer at Singapore’s hackerspace.sg

Place as a Strategic Differentiator

Not being in Silicon Valley is very helpful if you are trying to tap into developing markets like those in China, Korea, and Japan. It is also helpful if you don’t want to have to pay Valley salaries and sucked into the echo chamber there.

As an example, a skilled developer in Silicon Valley might cost you upwards of $120,000 per year; the same person in India would cost $12,000 per year and in Singapore they would cost $48,000 per year.

If you are trying to build a product to serve the Asian market, wouldn’t you rather base your company in Singapore?

Being in “a” place is more important than being in “the” place

It is widely assumed that internet technologies like Skype and email crush distance and make global distributed business possible. True, but there are exceptions.

Real creativity, trust, and ideation has to happen face to face. This is where the magic occurs. If you don’t spend time with people you can’t create.

New-technology tools can help with execution, but only after the team dynamics are in place; they are great for keeping people connected and plugged in, but suck at creating an initial connection.

Love your place. Find the other like minded souls who love your place and start companies with those people. The creativity you unleash in your own backyard is the most important competitive differentiator you have. No one else has your unique set of talents and point of view. Leverage it.

Every City is Becoming Self Aware — All at Once

I do not know of a city anywhere in the world that is not presently undergoing a tech community renaissance right now. This is a VERY big deal.

Every city in the United States along with Europe, Asia, and South America is now using the same playbook — implementing coworking, hacker spaces, incubators, angel investment groups, bar camps, meetups and other proven strategies that will have the effect of cutting off the oxygen supply to Silicon Valley.

Let me say it again: Silicon Valley is getting its global AIR SUPPLY cut.

For the last few decades, Silicon Valley has traded on the fact that people are willing to move there to start companies. The MAJORITY of valley companies are founded by foreign born entrepreneurs. What if they stop coming? What if they find the intellectual and investment capital that allows them to self-actualize in their home turf, where they already have a competitive advantage?

The fact that we have made it so hard for new immigrants to come to the valley and create startups just makes things that much worse. That is why the Startup Visa concept is so important if America – not to mention the valley – wants to keep excelling in innovation and the economy of ideas.

“Soul-crushing Suburban Sprawl” – Paul Graham

The Valley Kinda Sucks

Everybody says that the big draw to San Francisco is the weather. True, it can be pretty nice at times. But it can also be pretty miserable.

The reality is that the weather makes no f*cking difference if you are slaving away 26 hours per day on your startup; and the fact is that humans only really perceive changes in weather anyway: you’ll notice a nice day if it has been preceded by 10 rainy ones, or vice versa. Studies have demonstrated this. Look it up.

Paul Graham said it best, “Silicon Valley is soul-crushing suburban sprawl.” And he also suggested that places that can implement a bikeable, time efficient startup environment without sprawl have a significant competitive advantage over the valley.

Nearly every major city is becoming that place for its community of entrepreneurs. All at once.

So Why Travel?

It’s simple: to go to where the startups will be coming from. Investors who wait around for startups to show up in the valley are going to miss out on serious innovations and investment opportunities.

This means leaving the Lamborghini parked on Sand Hill Road and cabbing it to a gritty hackerspace in the Arab section of Singapore to meet the innovators who are building the future. And this is something that most investors think they are too good and too important to go do.

Fortunately there are scrappy, forward-thinking folks like McClure who are willing to go out there and embrace the future and begin the creative destruction the next wave of innovation will bring to valley culture.

Our challenges are too great to demand that innovation happen one way, in one place, with one set of people. Innovation needs to be systematized and distributed, and this is the opening act.

The Future of Entrepreneurship

I had a great conversation with Dr. Meng Weng Wong today, founder of Joyful Frog Incubator in Singapore. We pondered questions:

- In the future, will companies form teams and then try to get funding, or will entrepreneurs just gather, form ideas and try things?

- How do bands form? And are incubated startups just boy bands?

- Are we not always just betting on individual ability to execute?

- Doesn’t team (and execution) always trump idea?

- Is entrepreneurship a cycle? Shouldn’t exited entrepreneurs come hang out with first time entrepreneurs and try ideas together?

These are important questions in their own right, but the most important thing is that we are asking them. And so are people around the world. And it has nothing to do with Silicon Valley, the place.

Want in on the ground floor of this next wave of innovation? Understand the change that is coming and leverage it in your own backyard. Get involved.

Because I guarantee that in five years the Valley will be a very different place and that we will see thriving startup communities bearing real fruit in every major city.

Why go to the Valley? Good question.

A couple of acknowledgements: Shervin Pishevar pointed out that he and Dave McClure have been talking up the “Silicon Valley is a state of mind” concept for some time; he deserves proper attribution. Hats off, Shervin — the idea certainly resonates with me and I applaud both you and Dave for recognizing and acting on its power.

Also, Bob Albert — an entrepreneur I met in Singapore — came up with the “Is Silicon Valley Dead?” meme while we were chatting, and he deserves credit for crystallizing that idea. It’s been said before, but for different reasons; the forces driving this set of changes are distinctly different and I think we’ll be seeing this notion repeatedly over the next few years.

Dave McClure tweeted this article with the title “The Future of Silicon Valley Isn’t in Silicon Valley,” which is perhaps an even better title, even if it’s a touch less meme-friendly.

Thanks to everyone for engaging in this conversation!

May 16th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, trends

The American educational system deadens the soul and fuels suburban sprawl. It is designed as a linear progression, which means most people’s experience runs something like this:

- Proceed through grades K-12; which is mostly boring and a waste of time.

- Attend four years of college; optionally attend graduate/law/med school.

- Get a job; live in the city; party.

- Marry someone you met in college or at your job.

- Have a kid; promptly freak out about safety and schools.

- Move to a soulless place in the suburbs; send your kids to a shitty public school.

- Live a life of quiet desperation, commuting at least 45 minutes/day to a job you hate, in expectation of advancement.

- Retire; dispose of any remaining savings.

- Die — expensively.

Hate to put it so starkly, but this is what we’ve got going on, and it’s time we address it head-on.

This pattern, which if you are honest with yourself, you will recognize as entirely accurate, is a byproduct of the design of our educational system.

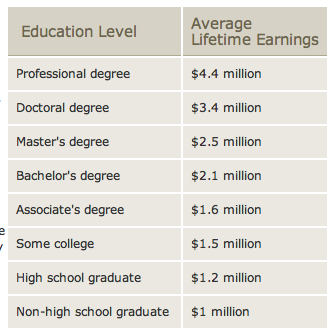

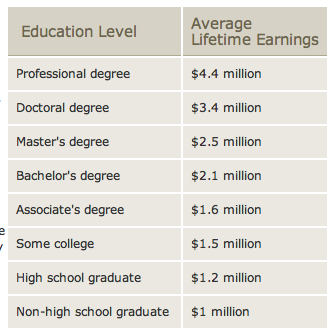

The unrelenting message is, “If you don’t go to college, you won’t be successful.” Sometimes this is offered as the empirical argument, “College graduates earn more.” Check out this bogus piece of propaganda:

But what if those earnings are not caused by being a college graduate, but are merely a symptom of being the sort of person (socioeconomically speaking) who went to college? People who come from successful socioeconomic backgrounds are simply more likely to earn more in life than those who do not.

There’s no doubt that everyone is different; not everyone is suited for the same kind of work — thankfully. But western society has perverted that simple beautiful fact — and the questions it prompts about college education — into “Not everyone is cut out for college,” as though college was the pinnacle of achievement, and everybody else has to work on Diesel engines or be a blacksmith. Because mechanics and artists are valuable too.

That line of thinking is the most cynical, evil load of horse-shit to ever fall out of our educational system. Real-life learning is not linear. It can be cyclical and progressive and it takes side-trips, U-turns, mistakes, and apprenticeships to experience everything our humanity offers us.

The notion that a college education is a safety net that people must have in order to avoid a life of destitution, that “it makes it more likely that you will always have a job” is also utterly cynical, and uses fear to scare people into not relying on themselves. Young people should be confident and self-reliant, not told that they will fail.

And for far too many students, college is actually spent doing work that should have been done in high school — remedial math and writing. So, the dire warnings about the need for college actually become self-fulfilling: Johnny and Daniqua truly can’t get a job if they can’t read and write and do math. See? You need college.

An Education Thought Experiment

I do not pretend to have “solutions” for all that ails our educational system. But as a design thinker, I do believe that if our current educational system produces the pattern of living I noted above, then a different educational system could produce very different patterns of living — ones which are more likely to lead to individual happiness and self-actualization.

If we had an educational system based on apprenticeship, then more people could learn skills and ideas from actual practitioners in the real world. If we gave educational credit to people who start businesses or non-profit organizations, and connected them to mentors who could help them make those businesses successful, then we would spread real-world knowledge about how to affect the world through entrepreneurship.

If more people were comfortable with entrepreneurship, then they would be more apt to find market opportunities, which can effect social change and generate wealth. If education was more about empowering people with ideas and best practices, instead of giving them the paper credentials needed to appear qualified for a particular job, it would celebrate sharing ideas, rather than minimizing the effort required to get the degree. (My least favorite question: “Will that be on the test?”)

Ideally, the whole idea of “the degree” should fade into the background. Self-actualized people are defined by their accomplishments. A degree should be nothing more than an indication that you have earned a certain number credits in a particular area of study.

If the educational system were to be re-made along these lines, the whole focus on “job” as the endgame would shift.

“A sturdy lad from New Hampshire or Vermont, who in turn tries all the professions, who teams it, farms it, peddles, keeps a school, preaches, edits a newspaper, goes to Congress, buys a township, and so forth, in successive years, and always, like a cat, falls on his feet, is worth a hundred of these city dolls. He walks abreast with his days, and feels no shame in not ‘studying a profession,’ for he does not postpone his life, but lives already. He has not one chance, but a hundred chances.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self Reliance, 1841

And so if the focus comes to be on living, as Emerson suggested it should be, and not simply on obtaining the job (on the back of the dubious credential of the degree), then the single family home in the suburb becomes unworkable, for the mortgage and the routine of the car commute go hand-in-hand with the job. They are isolating and brittle, and do not offer the self-actualized entrepreneur the opportunity to meet people, try new ideas, and affect the world around them.

The job holder becomes accustomed to the idea that the world is static and cannot be changed through their own action; their stance is reactive. The city is broken, therefore I will live in the suburbs. The property taxes in the suburbs are lower, so I will choose the less expensive option.

Entrepreneurial people believe the world is plastic and can be changed — creating wealth in the process. But our current system does not produce entrepreneurial people.

Break Out of What’s “Normal”

It may be a while before we can develop new educational systems that produce new kinds of life patterns.

But you can break out now. You’ve had that power all along. I’m not suggesting you drop out.

But I will say this: in my own case, I grew up in the suburbs, went to an expensive suburban private high-school — which I hated — where I got good grades and was voted most likely to succeed.

I started a retail computer store and mail order company in eleventh grade. I went to Johns Hopkins at 17, while still operating my retail business. Again, I did well in classes, but had to struggle to succeed. And no one in the entire Hopkins universe could make sense of my entrepreneurial aspirations. It was an aberration.

I dropped out of college as a sophomore, focused on my business, pivoted to become an Internet service provider in 1995, and managed to attend enough night liberal arts classes at Hopkins to graduate with a liberal arts degree in 1996. This shut my parents up and checked off a box.

I also learned a lot. About science. About math. About philosophy, literature, and art. And I cherish that knowledge to this day.

But I ask: why did it have to be so painful and waste so much of my time? Why was there no way to incorporate that kind of learning into my development as an entrepreneur? Why was there no way to combine classical learning with an entrepreneurial worldview?

Because university culture is not entrepreneurial. And I’m sorry, universities can talk about entrepreneurship and changing the world all they like, but it is incoherent to have a tenured professor teaching someone about entrepreneurship. Sorry, just doesn’t add up for me. Dress it up in a rabbit suit and make it part of any kind of MBA program you like; it’s a farce. Entrepreneurship education is experiential.

I had kids in my mid-twenties and now have moved from the suburbs to the city because it’s bike-able and time efficient. And I want to show my kids, now ten and twelve, that change is possible in cities. I believe deeply in the competitive advantage our cities provide, and I intend, with your help, to make Baltimore a shining example of that advantage.

I don’t suggest that I did everything right or recommend you do the same things. But I did choose to break out of the pattern. And you can too.

Maybe if enough people do, we can build the new educational approaches that we most certainly need in the 21st century. This world requires that we unlock all available genius.

May 11th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, philosophy, software, trends

This post started out as a reaction to yesterday’s post by Matt Mireles in New York City about the dearth of talent available to startups there. I felt it was relevant to the Baltimore/Washington area and shared it with some of our local leaders. It sparked a deep conversation — which I captured below.

Dave Troy to some area investors, entrepreneurs, and economic development officials:

This blog post out of NYC is a decent analysis of the problems that east-coast tech startups face.

- Drop in “federal sector” in place of “Wall Street” and you have an almost perfect analysis of our situation here in Maryland.

- Scarce technical talent wants to be employees, not co-founders for equity.

- A large well-funded ecosystem that sucks up available talent (Wall St, Feds, etc)

- Universities are barely aware of the startup ecosystem and do not contribute a good supply of talent

As the guy points out, a few good exits and some Stanford-like thinking can quickly change things. Tomorrow he’s writing some about how the NYC community is addressing this problem.

Roger London (investor, director of America’s Security Challenge):

I agree for the most part. I would tweak it as follows (comments embedded below).

1. Scarce technical talent wants to be employees, not co-founders for equity.

Totally agree, however technical talent in this region is not nearly as sophisticated and picky as the Palo Alto engineer sited in the blog. While most technical talent here would not take equity or options in lieu of a paycheck, I believe there are many that could find a suitable combination. This crop of “vested” technologists will anchor our next generation of technology entrepreneurs. They must first get a taste for the long-term value of equity and just as importantly realize a bit of a payoff so that a “paycheck” is no longer their motivation and requirement.

2. A large well-funded ecosystem that sucks up available talent (Wall St, Feds, etc)

I don’t think our technical talent goes to work for the feds, but they are hooked on the federal R&D heroin that so liberally “strings out” our technical talent making them addicted to and dependant on research funding, thereby unwilling to consider leaving the “shooting galleries” of the university and federal labs (got carried away with the drug metaphor). The feds could do a better job leveraging that investment by coordinating private sector collaboration, specifically startup collaboration with these technologists to open their eyes to the possibilities. In the absence of any progress there, we need to make a concerted effort to bring the eventual customers and serial angel entrepreneurs to the fed researchers to identify, shape and license technology that is desired by the market.

We need to find a more efficient way to produce more profitable and more successful startups. While mentoring, incubators and similar programs are valuable, the most effective way to increase the probability of success is to bring the customer to the startup table and have them help shape the requirements and solution. Who are the largest technology consumer enterprises in the state? State of MD government, Hopkins Healthcare Systems, Constellation Energy, T Rowe Price, Legg Mason, Lockheed, Fort Meade, Coventry, Marriott, Host, WR Grace, Catalyst, Discovery, Black and Decker, McCormick immediately come to mind. There are a number of technologies that most of these companies would want to procure because it improves their performance, customer service, security, bottom line, etc….things like high speed computing and distribution, more effective customer interaction tools, more effective customer security re their identify/information and customer logins, network security, building and vehicle fuel efficiency, etc.

Almost every agency and department of the federal government also has requirements for these and by establishing beachhead Maryland customers, we can stand up and provide credibility to young companies and then help springboard them into the federal government. With varying degrees of success, organizations already exist that follow this model but their efforts should be amplified.

3. Universities are barely aware of the startup ecosystem and do not contribute a good supply of talent

See above

As the guy points out, a few good exits and some Stanford-like thinking can quickly change things. Tomorrow he’s writing some about how the NYC community is addressing this problem.

NYC does not have the research funding that we have in the state and their solution might not be replicable here. Our ecosystem of capital, talent and customers is fairly unique which is another reason why we can’t just “copy” the innovation models from NYC, Boston/MIT, Silicon Valley, RTP or other innovation regions. The assets we have in this region that are not found anywhere else is the vast amount of federal R&D (#1) and the largest consumer of technology on the planet, the federal government. Unique programs need to be developed with those two factors deeply embedded that fosters emerging growth tech companies and helps to bridge the gap between research and market adoption. That work needs to be designed and operated by entrepreneurs and early stage investors. While collaboration with academia, federal and government stakeholders is important, their participation in the design and operations should be limited or we will get more of the same.

Bob Bloncheck, investor and serial entrepreneur:

My two cents:

I think we have the opposite problem as NYC. We have a lot of young techies trying to do start-ups in the region, and not enough of the non-technical entrepreneurs.

And when the experienced non-techies do give a start-up a try, they come at it from a professional services business model perspective, which is another side-effect of the government focus (indeed addiction, Roger) in the region.

Everything is driven by a time-and-materials mindset here that permeates not only government, but other big institutions as well, and contributes to the lower risk tolerance.

I just had another conversation with an entrepreneur last week who is considering abandoning a product approach and going to a services model. And it is because a large health care institution keeps telling him that they never would buy a product/technology from a young company. But they would do business with him on a services basis using his technology.

As many of us have learned the hard way, products and services are very different. And to the extent we are trying to foster a start-up ecosystem in the region focused on products, and not just more 3-10 person services spin-offs from other services businesses,

we need (as Roger said) unique programs that would encourage these large organizations to adopt products from local start-ups more readily (and not just technologies implemented using a services approach).

And we need the universities to start teaching more:

- Product management (not just project management or business analysis – they are different)

- Product marketing

- Market focus (in addition to customer or sales focus)

- Entrepreneurship

Business model is king, and it needs to be more than just billability, if we want a vibrant start-up culture in the region.

Mike Subelsky, entrepreneur and community leader:

Thanks for sending this Dave. I can only speak for my sector (consumer Internet), but this guy is DEAD ON. Maryland is awash in entrepreneurs with good (or good enough) business ideas, who are willing to take the big risks, but who just need someone who can build software who’s willing to take on some of that risk as well.

I know this empirically, because (due to my blogging about startups in Baltimore and due to Ignite), a lot of them end up emailing me asking for advice about how to find a decent programmer. I’ve had that conversation at least 10 times in the past 2 years. One of the most promising of these people actually just gave up and started teaching himself Rails so he could get his education software prototype out the door — when that guy starts looking for funding, if he even ends up needing it, look out!

My friend Gabe Weinberg, an entrepreneur in Philadelphia, had an interesting response (link).

I’m encouraged because we’ve been working on the kind of “drawing us out” he suggests for a few years now. But there’s a long way to go. Even just in my one little neighborhood, I’m still meeting very qualified technical people who have zero idea about the startup world in Baltimore. It’s not a matter of “do they prefer cash or equity” — it’s that they’ve never been offered and have no idea such a distinction might even be available.

Brad McDearman, Economic Alliance of Greater Baltimore:

We just took a group of 40 Baltimore business, government, education and non-profit leaders to Austin to see what we could learn from that market. We were hosted by the Greater Austin Chamber and the Lance Armstrong Foundation.

I think most participants from Baltimore would say two things stuck out related to how Austin deals with entrepreneurs…and the Austin people stressed these in their presentations to us:

- Celebrate entrepreneurs and wealthy people. Make rock stars out of them…and make sure wealthy people in the community and the entrepreneurs are hooked up. Get the wealthy people to invest in the start-ups.

- IC2 at the University of Texas – this is an institute at UT that stresses and supports entrepreneurship in the region and is what many point to as being the catalyst for driving the entrepreneurial culture in Austin. They put out white papers, provide support and networking for entrepreneurs…and connect people.

Many of us came away wondering how we make this happen in Baltimore. How can we get Hopkins to take a leadership role in Baltimore’s entrepreneurial and economic development efforts? JHU is a known entity and the folks in Austin kept talking about how lucky we are to have Hopkins given their research and world famous medical center (which Austin does not have). But JHU does not lead an economic development effort the way UT does.

They have created a culture in Austin related to entrepreneurship that even the corporate businesses respect and believe in…and it seems like they did it in a grassroots way (through the entrepreneurs themselves) and through the major institution (UT). But it doesn’t appear to have had much to do with the traditional business organizations (although the Austin Chamber does receive high praise for its broad impact and support).

Scott Paley, Baltimore entrepreneur, former New Yorker, to me:

Just from my own tiny perspective, this has long been a problem in NY. When I lived up there, I’d say I was contacted at least 5 times a year by non-technical startup founders asking me if I’d leave my own company to work with them as a technical founder. Even now I still get calls from non-techs asking if I know smart tech people in NYC.

Scott Paley to Roger London:

Hi Roger,

You wrote:

technical talent in this region is not nearly as sophisticated and picky as the Palo Alto engineer sited in the blog. While most technical talent here would not take equity or options in lieu of a paycheck, I believe there are many that could find a suitable combination.

I’m curious why you think this is the case (I’m not disputing the assertion – I don’t yet know enough about the local technical scene to be able to do that.) But, why should an engineer in Palo Alto be more sophisticated? Is it cultural? The experience of having gone through multiple startups, failures, and eventual successes? As a relatively recent “immigrant” to the Baltimore area (from NY), I’d like to try to understand the region better, so conversations like these are really helpful to me.

It does seem like in SV there is a general culture (or perhaps “badge of honor”) in starting a company, failing, starting another, and eventually hitting it big. In such a culture, people optimize for equity, but I’m not certain that should be characterized necessarily as “sophistication”. Could it be that, in general, technical talent in SV is younger and less established in the typical “traps” that make it hard for people to consider entrepreneurship? Failure is “easier” in a sense?

I can say from my own experience that the idea of failing was easier to contemplate when I was in my 20’s without a mortgage and kids than it would be today.

Of course, this seems line of thinking seems most relevant for first time entrepreneurs, which takes us back to fixing what Dave wrote in the first email:

Universities are barely aware of the startup ecosystem and do not contribute a good supply of talent.

Roger London to Scott Paley:

Scott- the article described the Palo Alto engineers thinking as “sophisticated”, not my words. I do think most of what you describe re multiple startup experience is true.

Experience gained over several startups for several years each likely puts that person around 30 years or older. I don’t think however you can replicate that experience (sophisticated thinking) by working with universities and getting a larger volume of people in their 20’s.

This region also has a lower tolerance for failure. Rather than throw young people to the wolves and try to make them entrepreneurs realizing in this region you cannot erase the black mark of a failed venture, we should make them entrepreneurs-in-training and help place them in a growing company where they can still earn a paycheck, but have some skin in the game while simultaneously experience but not be responsible for the critical elements of successful entrepreneurship…. how to acquire key initial customers, product development, building a team and staff, operational infrastructure, raising capital, etc.

Jared Goralnick, entrepreneur and community leader shared an interesting response by David Fisher:

– Have better ideas and bring more to the table: There are a few non-technical people that I’d follow anywhere and its because they do have consistently great vision and ideas. Show people that you can lead and followthrough. One of my good friends Tim Hwang can’t code at all (AFAIK), but I’ve seen him execute with the Awesome Foundation, ROFLcon and the Web Ecology Project. I know that if he gets a great idea, that he will hold up his end. Do things like this and you’ll have no problem finding developers and technical co-founders.

It’s true that if you’re a “tested entrepreneur” then people will want to be part of your vision, but most people aren’t their first time around. Still, I think this speaks to the value of community involvement in lieu of us having a really technical and available scene.

I don’t think it’s actually particularly easy to find co-founder engineers or engineers in general in the valley. I bet we’re going to feel this way everywhere…

Jared Franklin, product manager at Bill Me Later:

Thanks for posting the responses in “Baltimore Area Leaders Sound Off on Startup Scene.” I completely agree with those who cited the lack of support and production from our Universities in the area. I graduated last year from Loyola as an MIS major and now work for PayPal/Bill Me Later as a product manager. I would never have landed the job if I didn’t intern for Bill Me Later 20+ hours a week for 2.5 years of my time in college. School simply isn’t enough.

Our MIS major consisted of <10 graduates in the 2010 class and I'd consider it to be the most "entrepreneurial" major at the school. Our biggest class in the business school were either general business majors or finance majors. The school did not do enough (or anything) to teach students what other majors existed or what type of jobs they help you develop skills for. Additionally, the MIS majors capstone project consisted of a business plan and a non-functioning prototype of a web product. However, a portion of a semester and lack of coding skills did not help. I wish they paired us with the CS majors to develop a product together. This would have been beneficial for both the MIS majors and CS majors. I find myself in the same predicament now, one year out of college. I generate ideas (for projects outside of work) but need someone who can code. I was exicted to see Bob Blonchecks point of view stating that he thinks we have a lack of non-technical entrepreneurs.

Anyway, thanks for the post. It was great.

Please feel free to post YOUR thoughts and comments!

What are YOUR thoughts about East Coast startup culture?

May 11th, 2010 — design, economics, politics, trends

For the last year I’ve been developing an idea for a documentary film tentatively titled “Sticker Movie” about bumper stickers and how they express tribal identity and territory. Someone inquired about the status of the project and this was my response. Consider it a glimpse into the creative thought process.

“Sticker Movie is on hiatus for the moment, mostly while I seek funding and further develop the concept. However, the more I’ve meditated on the idea, the more I have come to believe that stickers indicate something very fundamental about the human psyche, specifically the amygdala and its function in society.

Humans behave differently when they feel threatened; brain function shifts from cerebral cortex to amygdala, which mediates flight/fight response. I believe stickers are associated with territorial instinct, as originated from the amygdala, and that much of the definition of “liberal” and “conservative” rests on how specifically people modulate their amygdala/cerebral functions. I believe this is partially genetic and partially environmental. People’s early experiences (bullying, racism, teasing, aggression, prison, certain sports) can definitely activate a “zero-sum” mentality which is dominated by the amygdala.

It’s been observed that siblings are more competitive but less successful than only children. Siblings fight amongst themselves for resources and attention, while only-children may have more opportunity to be creative. Zero-sum vs. positive sum thinking, IMHO.”

I’m an only-child. And I believe that if we can deactivate the amygdala in our political discourse, we can positively affect the world. What do you think about stickers, the amygdala, and zero-sum thinking?