Entries Tagged 'trends' ↓

March 3rd, 2010 — business, design, economics, philosophy, trends

There is an insurance sales office not far from my home with a letterboard sign out front that proclaims, “The real risk is doing nothing.” Of course, they wanted you to think about the risk of not having insurance. But it got me thinking about entrepreneurship and how entrepreneurs change the world through their actions.

And I’m not talking about changing the world in some pie-in-the-sky, abstract kind of way. Recently I’ve been reading the work of entrepreneurship researcher Dr. Saras Sarasvathy, whose theory of “effectuation” states that entrepreneurs actually create the world around them through their actions.

Sarasvathy has interviewed hundreds of entrepreneurs and one common thread she has observed is that entrepreneurs believe that they are called to act when they see an opportunity to create change; they know that if they do nothing, they will achieve nothing, and things will stay the same.

And so entrepreneurs evaluate their options — what and who they know — to take a calculated risk to move a little closer towards a goal. That action might be as simple as putting together a meeting of stakeholders or researching a topic. And with that very first action, they’ve changed the game.

The entrepreneur has widened the opportunity by involving more people, or by knowing more about the subject, or attracting investment. And so in a very real way, she has changed the world around her to make the world more hospitable to attaining the goal. Her actions do not cause the goal to come true directly; it is the compounded effects of the entrepreneur’s actions that lead to a world where the goal becomes possible.

What Really Motivates Entrepreneurs

A purely rational evaluation of entrepreneurship would suggest that it occurs when someone perceives an unmet market opportunity and then proceeds to allocate resources to address this unmet need. Sarasvathy observes that this is almost never how entrepreneurs really operate.

Indeed, most entrepreneurs are haunted by the risk of doing nothing. They might say, “Well, I’ve always wanted to try this idea and I think it might work. How will I feel if I don’t pursue it?” And then they look to limit risk. Often, if someone can craft a scenario where the downside risk is affordable, they go for it. They ask, “What’s the worst that could happen? I lose a year and have to return to my job.” They are not typically motivated by the lure of the upside, but rather the fear of not acting!

Can Entrepreneurship Be Taught?

Are entrepreneurs born risk-takers, or are they just regular people that are applying a particular kind of logic? Sarasvathy suggests the latter. She says that there is nothing about her study of entrepreneurs that would suggest that there are particular personality traits that distinguish entrepreneurs from others propranolol sans ordonnance. The only difference is their use of “effectual logic” and the subsequent learning that comes from its use.

Entrepreneurs ask, “What do I know, and what can I do with it?” They then take steps that help to change the game. Then they ask, “What else can I do with it?” Expert entrepreneurs engage in an iterative process of changing the world and then with each round re-evaluate the opportunities that their previous actions have made possible. Surely it’s possible to teach this process to people in the same way that it’s possible to teach a high-schooler how to think scientifically.

The differences come with experience. First-time entrepreneurs are likely to make mistakes around trust and judgment: they tend to trust people too little or too much, misread the character of a partner, or underestimate the importance of foundational elements like operating agreements. And so while many entrepreneurial enterprises fail, each failure causes the long-term success rate for an individual entrepreneur to increase. Failure helps entrepeneurs to know what pitfalls to avoid and it also teaches him fundamental lessons about his own strengths and weaknesses. This is why it’s so essential for entrepreneurs to pick themselves up and try again! Failure is essential to the creation of the expert entrepreneur.

The Role of Entrepreneurial Action in the World

One of the things that puzzles Dr. Sarasvathy is how effectual logic is used routinely in private sector business but is rarely applied to solving the deep social problems that we face in the world. Some beneficial businesses like micro-lending site Kiva.com got started through effectual thinking (you need $27 to break free from debt? Here’s $27), but for the most part we have consigned the world’s most pressing problems to the work of charitable foundations and non-profits. And because of the way these entities are funded (donations and partnerships), effectual logic cannot often be applied.

Sarasvathy suggests that a wave of social innovation might be unleashed if we were to change the funding model of social enterprises to better enable effectual thinking — primarily because effectual thinking is very efficient and good at minimizing risk at each step. And this goes beyond the current trend of “social entrepreneurship” that suggests that there is a class of problems that is suited to entrepreneurial thinking, and class that is not.

Why shouldn’t all entrepreneurship produce social benefit, and why shouldn’t all social problems be soluble through the application of effectual logic? This is an open set of questions, but certainly they represent the challenge of our time.

The Moral Imperative

If we believe that entrepreneurs literally affect the world to alter their own odds of success then we must also believe that there is a legitimate role for human action in the world.

The theory of effectuation additionally suggests that entrepreneurs are designers: at each stage they are using design thinking to imagine a set of possible solutions using available assets.

If entrepreneurs, through their actions, can help design potential solutions to the world’s most pressing problems, then isn’t the real risk doing nothing?

March 2nd, 2010 — art, baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, trends

Google CEO Eric Schmidt recently outlined a case arguing that America needs to address its ongoing “innovation deficit” and spur entrepreneurship and creativity in meaningful new ways.

How did we get here? Why is it that America has an innovation deficit? It’s simple: we have lulled ourselves into complacency. America is bored because we have made ourselves boring.

Unleashing Self-Actualization

What do we mean when we talk about innovation and creativity? Really what we’re talking about is what psychologists call self-actualization. Put simply, it’s nothing more than realizing all of your unique capacities and putting them to good use. Self-actualization occurs best when it’s in the company of others who are doing the same. Companies that achieve remarkable results are typically loaded with people who are either self-actualizing or on a pathway towards it.

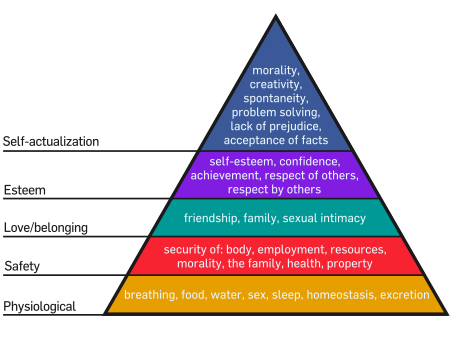

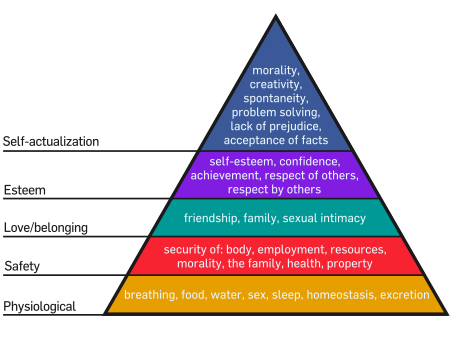

Abraham Maslow described this pathway as the “hierarchy of needs” to highlight the fact that people cannot become fully self-actualized if they are concerned with other more basic needs like food and security.

Like the USDA food pyramid, Maslow’s hierarchy identifies some important elements, but the idea that there is a strictly linear progression towards self-actualization, or that it is inclined to occur naturally, is probably wrong. Looking at the world around us, it’s easy to see examples of people whose lives who have petered out somewhere in the middle of his pyramid, even though their baser needs have been met.

I believe this is because we have designed 21st century America in such a way that we short-circuit the process of self-actualization in a number of important ways.

Problem 1: Suburbs

Self-actualization occurs best when people are able to connect face-to-face to discuss real-world ideas, try things out, and play. This means intellectual conversation with a diverse range of people, including a broad range of views. It means exposure to the arts, to music, and a shared desire to solve meaningful problems.

Suburbs short-circuit these important pathways for self-actualization in these important ways:

- Slowing movement: people are dispersed – gathering requires use of cars

- Lack of diversity: suburbs tend towards less diversity of views, not more

- Diverts self-actualizing motivation into materialistic and trivial pursuits

The first two points are obvious enough, but let’s spend a moment on the last one.

Suburbs divert self-actualization into pursuits like neighborhood-hopping and home improvement. It’s not surprising that we just suffered the effects of a housing bubble. With millions of peoples’ self-actualizing efforts poured into drywall and granite countertops, there was simply a limit to how much housing and home-flipping we can endure. It doesn’t do anything. Working on housing is first-order toiling, not long-term advancement.

Is it surprising that the icons of the housing bubble years were “Home Improvement,” “Home Depot,” and the SUV? The SUV was literally a vehicle for improperly diverted self-actualization: if I have a vehicle that lets me improve my basement and my backyard, I can become the person I want to be.

Problem 2: Artificial Scarcity of Opportunity

Suburbs have had other unfortunate side-effects: we have allowed corporations to define the concept of work. By dispersing into our insulated suburban bubbles, we have largely shut down the innovative engines of entrepreneurship that used to define America. Where we might fifty years ago have been a nation of small businesses and independent enterprises, we are more and more becoming reliant on corporations to tell us what a “job” is and what it is not.

To the extent that we are not spending time together coming up with new important ideas, we are shutting down opportunities for ourselves. And corporations are happy to reinforce and capitalize on this trend. Opportunity is unlimited for people who are legitimately on a pathway towards self-actualization. We choose not to see it because we think of “jobs” as something that can only be provided by “companies,” and not created from scratch by collaboration.

Problem 3: Reality Television

Reality television is an ersatz reality to replace our own. It steps in where we’ve failed at self-actualization. It is both a symptom and a cause of our failure. As a symptom, it shows that we have so much time on our hands that we can spend it worrying about somebody else’s ridiculous “reality.” As a cause, this obsession can only be serviced at the expense of our own shared reality.

Problem 4: Car Culture

As a society, we spend way too much time in cars. Some of this is due to the issues I already raised about suburban design. But besides that, we spend a ridiculous amount of time stuck in traffic, waiting at red lights, and trekking around our metropolises.

Cars are fundamentally isolating. Time spent in a car is time you can’t spend doing something else. Sure, they can be useful, and I’m not anti-car, I’m just anti-stupid. If we as a society are burning many millions of hours each week in our cars stuck in traffic and covering unnecessary miles, it’s hard to see how that’s helping us become self-actualized (unless it’s in the backseat) and become more innovative. It’s a tax on our time.

Some have also suggested that one reason we have so many prohibitions on what we can do while driving is because we really just don’t like driving that much. Maybe the problem with “texting while driving” is that we are driving, not that we are texting. Maybe communication is more important societally than piloting an autonomous 3,000 pound chunk of metal and plastic?

A Solution: Well-Designed Cities

We’ve had the solution under our noses all along, but we’ve chosen to let our cities languish. Historical facts about America have led our cities to evolve in particular ways that differentiate them from some of our peers in Europe in Asia. But there is hope, and we must recognize the assets at hand in our cities.

Cities offer higher density populations which lead in turn to innovation and a flourishing of the arts. They lead to efficiency of movement and face-to-face communication, which is absolutely essential for intellectual self-actualization and entrepreneurship. Well designed public places let people interact and share, and also provide a platform for festivals, celebrations, and entrepreneurship. There are simply too many positive assets to ignore.

Arguments that American cities are unlivable today are tautological and self-reinforcing. The very problems that are most often cited (crime and education) are the same problems that would most benefit from entrepreneurship and real long-term economic development activity.

The root cause for the abandonment of our cities is race. In the case of Baltimore, WASPs left when Jews became concentrated in particular areas. Jews left when blacks became concentrated in particular areas. And “blockbusters” capitalized on the fear by benefiting on both ends of these transactions. In 50 years, Baltimore (and many American cities) changed dramatically.

Young adults today simply do not remember the waves of fear that sparked this initial migration. It may be a stretch to say that we are entering into a “color blind age,” but we do live in an era where we elected the first black president. I believe we are at the very least entering an age where people are willing to consider the American city with fresh eyes.

We are at a turning point, on the cusp of a moment when people will start looking at our cities entrepreneurially, for the assets they possess rather than the history that has defeated them. We are at a point where we can forget the divisive memories of the mid-twentieth century and forge a future in our cities that is based on shared values of self-reliance, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

Designing Our Future

The design constraints we have proposed for the last 50 years — abandoning our cities, relying on cars, building suburbs and big box stores — have led to the America we see today. And I ask simply, “Do you like what you see?”

We’ve let the culture wars frame these difficult design problems for too long, and it’s time now to put them behind us and start to ask questions in fresh terms. It’s clear now the answer likely doesn’t involve old-school silver-bullets like “Public Transportation,” because simply overlaying transport onto a broken suburban design doesn’t fix anything. Building workable cities and investing in long term transportation initiatives that help reinforce a strong urban design is much more sensible.

And make no mistake: self-actualization is an intellectual pursuit, and the kinds of cities that promote real self-actualization, innovation, and entrepreneurship must become hotbeds of intellectual dialog. Truth and acceptance of facts is an underlying requirement for self-actualization, and we can no longer delude ourselves into thinking that a society built on suburban corporate car-culture makes economic sense.

To continue to do so is to prolong and widen America’s innovation deficit.

February 16th, 2010 — business, design, economics, philosophy, trends

In my recent post on Effectuation, I highlighted the work of Dr. Saras Sarasvathy, who coined the term.

One of the points she makes in her book is that entrepreneurship is a branch of design thinking. This is an absolutely brilliant insight.

First, if you are the sort who thinks that design is a discipline centered around making chairs, teapots, web pages, or books, you should read up on the topic (see below). Design is a pattern for thinking, and while design thinking often produces the “beautiful things” which we have traditionally associated with design, widespread application of design thinking is beginning to have far-reaching effects on our society.

Design thinking starts with a simple grab-bag of elements: one or more goals, and one or more constraints. Constraints might be size, cost, weight, and psychological properties of the user. Goals might be to solve a particular problem or to make money. It is then the designer’s job to propose a solution that carefully considers the effects of the available solutions to propose the best possible, most beautiful and simplest solution.

What do I mean by the effects of a solution? If you follow popular mathematics at all, you might be familiar with the work of Benoit Mandelbrot, who suggests that reality is fractal and folds in on itself to produce patterns of amazing complexity from simple constraints. Mandelbrot’s formulae are a kind of simple design constraint that produce patterns of stunning complexity.

Similarly, designers can create complex patterns on the world by building systems or objects that include very simple design constraints. We see examples of these effects every day: the poorly designed chair that pulls apart its base after a bit of use, or the well-placed door handle that gets shinier and more beautiful with every use.

But these are just objects. What about systems and institutions like the United States government or the American public school system? The US Constitution is a piece of design, as are the laws that built our school system. The effects that those designs are now producing are sometimes more corrosive than their designers would ever have imagined. Both of those institutions are in need of “design refreshes” to clear away unintended corrosive effects.

Entrepeneurship and Design

Sarasvathy suggests that in the process of effectuation, the entrepreneur first makes an assessment of what assets and connections are available to them and then asks the simple question, “What can I do with it?”

At this moment, the entrepreneur becomes a designer. They are looking at what they have as design constraints and trying to move themselves closer to their goals. Sarasvathy makes a key additional insight; after the first round, the entrepreneur asks, “What else can I do with it?”

This puts the entrepreneur into the position of being a broad-based free-thinker, going beyond the simple condition of “how do I work within these constraints to achieve a goal,” but instead towards the question “what is the set of goals that I can achieve elegantly within these constraints?” This is a powerful inversion and is one that gives an imaginative entrepreneur an amazing power to transform society.

And here is a key point of difference between society’s conception of designers and entrepreneurs, even though they effectively perform much of the same kind of thinking: a designer is typically handed constraints and goals and asked to produce a product. An entrepreneur is issued constraints (the context of their life situation) without specific goals and rises to the opportunity to choose both the goals and the path.

I sometimes get frustrated with “designers and architects” because they cannot think of their own work outside of the context of their clients. They blame their own inability to do great work on the lack of vision of their clients, and I have to say I am apathetic to that line of thinking. It is time that designers and architects throw off the shackles of their clients and become entrepreneurs themselves. Show us what you believe, not what you can be paid to do.

Great entrepreneurs have been finding ways to finance their own design thinking for eons. It’s time that businesspeople start understanding that they are designers, and it’s way past time for the greatest designers to become their own clients and produce the great work they are called to create.

Some Suggested Reading

February 14th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, travel, trends

Several months ago, this article from the Pew Research Center categorized several states as sticky, magnet, or both; sticky means that people who live there tend to stay there, while magnet means that it attracts people. Some states (Arizona, Florida, Maryland) are High Magnet/High Sticky, while others are one or the other, and one sad batch is neither (Iowa, New York, West Virginia).

What this study doesn’t tell us is very much about what those places are actually like, only the “raw numbers” about mobility and retention. For example, my home state of Maryland is described as “magnet/sticky” (woot) but so are Arizona and Florida, and as far as I can tell, these three states share little in common. Certainly the recent real estate bust was felt worse in those places than here.

I believe that in Maryland’s case, we are both the wrong kind of magnetic and and the wrong kind of sticky, and so to describe Maryland in this way is counterproductive because it assigns a positive spin to some inherently negative patterns of movement.

For example: suppose Maryland is “high magnet” because it attracts people who want to work for federal government contractors. This increases the per-capita income but puts pressure on roads, exacerbates suburban sprawl, and adds people to the voting base who often don’t understand local issues or have personal experience with the landscape around them. I’d call this effect neutral, if not negative.

Suppose Maryland is “high sticky” because we retain 99.5% of our college graduates (a number I’ve heard tossed around). But suppose we export .5% of our very best and brightest and our natural born “effectuators?” And suppose that the smart people we do retain get sucked into government? Again, not necessarily a bad thing, but it doesn’t necessarily lead to the most creative entrepreneurial landscape sometimes.

Maryland has a great deal going for it, but articles like this are meaningless and enhance a simplistic, 19th century view of how we want to build our society. Who are we building our society and economic structures for?

If we are building them for ourselves we need to start thinking about how they serve our everyday experience as people. I have more thoughts on this. If we want to build our society for corporations and a 19th-century conception of what education, production, and economic value is then idiotic oversimplifications like “high magnet, high sticky” might be useful.

I believe we can and must move past such Orwellian, disingenuous oversimplifications.