Entries Tagged 'politics' ↓

October 10th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, trends

When I was about four years old, my parents asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up. My response? A cashier. Why? They were the ones who got handed all the money.

Today, when people cite crime and education as the two major problems facing America’s cities, the knee-jerk response is to “protect city education budgets” and “put more cops on the street.” This is the same kind of simplistic logic I used as a child, and it’s just as wrong.

If this was how things worked, the safest cities in the world would be populated entirely by police, and the highest levels of education would be attained by those countries who spent the most on teachers and schools. This also is not true. Excluding repressive regimes, the areas with the least crime and most educated populations tend to be places where all citizens have access to the same opportunities.

Access to Opportunity

The new film by Davis Guggenheim, “Waiting for Superman,” chronicles a year or so in the life of a handful of students of different backgrounds as they struggle to get access to the educational resources they need to thrive. The heart-wrenching conclusion shows these kids – all but one – get denied that opportunity by a system that is clearly broken and unfair. 720 applicants, 15 spots. You get the picture.

If America is going to have a public school system, this kind of unfairness should not be tolerated. What happens to the kids that don’t get into the schools that can help them thrive? Should people have equal opportunity? Most people would say “yes.”

How We Got Here

Economic vitality is a kind of spotlight: it shines a light on things that need fixing, and provides the funds and political power to do so. Since our cities were torn apart by race riots and the global consolidation of manufacturing, the resulting precipitous decline in economic health has meant that cities have operated substantially in the dark. Watchdogs have been absent, and grassroots efforts have been underpowered.

American cities have reached a kind of feudal equilibrium. Politicians in power have little incentive to promote the kind of broad-based economic growth that could ultimately result in their ouster, but they can’t let things deteriorate so badly that everyone leaves – also stripping them of their power. And so American cities walk the line: with crime, schools, drug use and taxes locked at levels that are tolerable to just enough people that they are still worth milking, all while politicians hand out favors to power-brokers and childhood friends. Enough.

Ending the Abuse, from the Bottom Up

I wrote in my previous post that cities are now prime locations for idea-based industries. Over time this will mean an influx of wealth into cities as well as an increase in poorer populations in the suburbs.

Economic vitality in our cities borne from idea-based industries will result in a demand for accountable leadership and provide new levels of participation. In short, the feudalism will end when creative people begin to use their economic power to demand real change. The 40 year free ride is over.

Too many people in cities have resigned themselves to the idea that politics is a top-down enterprise — that it’s primarily influenced by the machine, by power-brokers, by community leaders, or by churches. Or that there’s a “turn based system,” where everyone who serves is given an equal shot unless they do something wrong.

That’s just wrong. American city politics from now on will be a bottom-up grassroots affair dictated not by the economics of writing checks to campaigns, but by the interdependent economics of jobs and a shared vision for the future of places that people care about.

Restoring Trust

To be workable, all power relationships must be a compact founded on shared values. Kids trust teachers that have their best interests at heart. Citizens trust cops who behave consistently and fairly. People trust politicians who put the civic interest ahead of their own.

There is nothing that ails us that cannot be fixed by restoring these trust relationships.

In “Superman,” Guggenheim asserts that bad teachers are kept around out of a “desire to maintain harmony amongst adults.” It’s difficult to stand up and fight to end someone’s teaching career, but it’s what’s required. To fail to do so is immoral.

It’s easier to keep getting a paycheck than to make enemies. And certainly there are dozens of systemic problems that make firing teachers very difficult. But that’s all that’s wrong with our schools, our police and our politicians: a simple failure to defend our core values.

And if we cannot agree on those core values – if a desire for personal gain exceeds a willingness or ability to serve the public – then those people deserve to be called out.

The Game Is Up

To be an old-school politician in a major American city today is to be in the way of a major cultural shift. Idealistic, intelligent, educated millennials armed with 21st century political weapons are coming, and they are going to ask why?

Why is the city so screwed up? Why are these jokers in power? Why are these incompetent teachers shuttled between schools? Why is more money spent on development deals for cronies than on parks? And why the hell can’t we clean up the blight that makes any trust or pride impossible?

Should we spend more money on schools or police? More than likely, all we need to do is let smart young people start asking questions. Crime and education take care of themselves if those that have violated the public trust can be removed from power. And with a little attention and common sense, we can ensure that more kids have a shot at the same opportunities.

Because in the end, crime, education, and blight are really just one problem, and it can be cured at least as quickly as it developed.

August 1st, 2010 — art, baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, software, trends

Putty Hill, a film by Matthew Porterfield (2010)

Something amazing is happening in the world of filmmaking. Crowdsourced funding mechanisms like Kickstarter.com are enabling a new generation of filmmakers to get a foothold doing what they love, where they want to do it. They’re using social media to find acting talent, and new digital camera technologies are making it possible to create amazing high quality films for a fraction of what it used to cost.

Matthew Porterfield

I’m particularly impressed by the work of Baltimore filmmaker Matthew Porterfield, whose films “Hamilton” (2006) and “Putty Hill” (2010) exemplify the new kind of “cinepreneurial” skillset which will certainly come to define 21st century filmmaking. (You can read here about the funding and creative process behind Putty Hill.)

Porterfield is a nice, unassuming guy who teaches film at Johns Hopkins and directs his students that if they want to make documentaries, they need to go to New York, and to go to Los Angeles for pretty much everything else. For today, this is sound advice. It’s the same kind of advice you’d give talented coders looking to unleash the next big web technology — go to San Francisco, because it’s where the industry is centered — at least right now.

But if you ask Porterfield why he doesn’t take his own advice, he’d likely offer a cryptic sort of answer — that he’d considered it but really couldn’t imagine himself anywhere else. I don’t know him well enough to speak for him, so I hope he weighs in here. But Matt and I are kindred spirits: we both are actively choosing place over anything else, and investing our time and talent to make it better.

Let’s Invest in Maryland Film, Not in Hollywood

Baltimore and Maryland have been the home to many well-known movie and television productions over the years, not the least of which have been Homicide: Life on the Street, The Wire, and a slew of Baltimore native Barry Levinson’s films including Diner, Tin Men, and Avalon. And most all of these productions received significant subsidies from the State of Maryland.

As budgets have continued to tighten, the O’Malley administration made a strategic decision to cut back on investment in film production subsidies. And that has probably been a very wise decision. Other states have been more than willing to outbid Maryland, offering ridiculous breaks. And Maryland really doesn’t need to be in yet another race to the bottom.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008)

The film The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) was based on a short story by F. Scott Fitzgerald (who lived around the corner from me in Bolton Hill when he wrote it), and it was originally set in Baltimore (original text). Yet the film version was set in New Orleans and had a subtext about a dying woman retelling the story as Katrina bore down on the city. Why? Subsidies. New Orleans offered more subsidies than Maryland would. And so the story was changed and moved there. Who knows if the Katrina storyline was a condition in the contract!

I don’t really have an opinion about whether Benjamin Button should have been filmed in Baltimore, but I do have an opinion about engaging in zero-sum games with 49 other desperate states: it’s bad policy. And I also think the time has come to admit that big movie studios are the next big dinosaur to face extinction. Why should Sony or Disney or Universal make the bulk of the world’s content when every man, woman, and child has access to a $200 HD camera and a $999 post-production studio?

Investing in Cinepreneurs

John Waters is one of Baltimore’s great artistic assets. And it’s not because of film subsidies. His work is known worldwide, and it celebrates the quirky, distinctive voice of Baltimore. Matthew Porterfield is distinctive and quirky too, and he makes beautiful pictures: he’ll be next to make his mark. And there are dozens more teeming around places like MICA, the Creative Alliance CAMM Cage, Johns Hopkins, Towson University, and UMBC. We need only to nurture their talent and the ecosystem.

Browncoats: Redemption, 2010

Another film, Browncoats: Redemption was made locally last year and created by local entrepreneurs Michael Dougherty and Steven Fisher. It is utilizing an innovative non-profit funding model. The film’s is raising money for five charities and it leveraged social media and Internet to recruit 160+ volunteers and market the film.

Instead of blowing money on Hollywood productions that bring little more than short term contract and catering work to Maryland, why don’t we instead start investing in the artists in our own backyard? Just as IT startups have gotten much cheaper to jumpstart, it’s now possible to make films for anywhere from $50 to $150K. If we dedicate between $5M and $7M to matching funds raised via mechanisms like Kickstarter, we could make something like 150 to 300 feature length films here in Baltimore. This would unleash a new wave of creativity that would yield fruit for decades to come, and put Maryland on the map as a destination for filmmakers.

We already have great supporters of film in the Maryland Film Festival, Creative Alliance, and many other organizations. It wouldn’t take much to get this off the ground. Instead of going backwards to the 1980’s in our view towards film production (as former Governor Ehrlich has recently proposed), let’s take advantage of all the available tools in our arsenal to jumpstart the film industry and move it forward in Maryland.

For every new artistic voice we nurture, we’ll be building Maryland’s unique brand in a way that no one else can compete with. It will make an impression for decades. And investing in film and the arts will help the technology scene flourish as well. Intelligent creative professionals want to be together. And coders and graphic artists think film and filmmakers are pretty cool.

We shouldn’t let an aversion to the failed subsidy policies of the past get in the way of forging a new creative future that we all can benefit from. We can invest in the arts intelligently. Let’s start today.

July 31st, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, software, trends

I live in Baltimore, in the great state of Maryland. I’ve been studying the economic development process here for many years. While this post contains observations specific to Maryland and Baltimore, the concepts likely apply in other geographies as well. I am curious to hear your perspectives from where you live.

Shh… they don’t know they’re obsolete!

Shh… they don’t know they’re obsolete!

There’s a growing disconnect in economic development. Government sponsored economic development outfits are tasked with 1) growing the tax base, 2) attracting new businesses, 3) helping existing businesses grow, 4) aid in the creation of new businesses, 5) develop and grow the local workforce.

In Maryland, the State Department of Business and Economic Development traces its roots back to the Bureau of Statistics and Information, which was formed in 1884 to compile statistics about agriculture and industry. As industry shifted dramatically in the 1950’s and 1960’s, the focus shifted to providing small business loans and seeding the development of new jobs.

Vast consolidation in manufacturing starting in the 1970’s meant that states were particularly anxious about job losses. The loss of a single plant could deal a staggering blow to the tax base, and could mean a huge loss of jobs — often leading to a demoralized workforce and a downward spiral of negative economic growth. (Think Detroit.)

The Zero-Sum Game

As a result of this process, states began to engage in heated battles to attract and retain manufacturing facilities. The primary tool available to economic development authorities has traditionally been tax credits and other “incentives,” which might include deferred taxes, regulatory considerations, and a “turnkey” permitting process.

As states rushed to use these tools to attract and develop these “big projects,” a kind of zero-sum game emerged between states trying to attract companies and capital. Large corporations were now in a position to effectively “shop” for the sweetest incentives. As you likely know, states have not shown much restraint in their willingness to offer breaks. In fact, it’s all been very embarrassing — a rush to the bottom, where states compete not on their own merits, but on how many baubles they can afford to dole out to their latest suitors.

This disease has so stricken governments, Governors, and their economic development teams that they’ve developed an unhealthy obsession with “big projects” as well. Folks in government, who on average have very little first-hand experience with entrepreneurship or business, tend to think in “causal” terms. If we do X, then Y will happen. And so the logic is that if you want a big result, take a big action.

And so they chase after smokestacks and big iron, trying to attract heavy manufacturing, big developments by big developers, corporate headquarters, sports teams, stadiums, and slot parlors. But here’s the paradox: these projects, while flashy, just don’t pay off. Tax subsidies are never recouped, and the jobs that are created tend to be bottom-of-the-barrel service industry jobs that barely support a living wage.

Baltimore’s subsidized Camden Yards stadium produces $3 Million per year in tax revenue, but costs Maryland taxpayers $14 Million per year in subsidies. The heavily subsidized Ravens stadium produces $1.4 Million per year but costs taxpayers $18 Million. Failure to impose or enforce job quality standards as part of subsidy packages provided to multiple hotel developments in Baltimore has led to many low-wage jobs and nearly none of the higher paying jobs that were promised. (These conclusions were taken from this report by the group Good Jobs First.)

New Approaches

Maryland, in an effort to develop a strategic focus on biotechnology, instituted a $6M program of tax credits (later increased to $8M) for investors in biotechnology companies. The program has proved wildly popular, and to Maryland’s credit, it recognized the importance of investing in an industry that had already taken root here and, thanks to the presence of the National Institutes of Health and Food and Drug Administration, was a natural strategic focus for our area.

The only question is how effective the biotech tax credit is at actually developing these kinds of jobs in the long term. It’s a little early to judge how effective the biotech tax credit program will be, but we can make these qualitative observations about that industry:

- Developing a new biotech product (whether a drug, device, or process) has a very long lead time.

- Because of long lead times and the need for highly-skilled workers, development is very expensive.

- Failure is common and is often stark: big bets on molecules that don’t pass approval processes or are copied by competitors can lead to epic financial losses.

- The kicker: successful companies are often acquired by firms based elsewhere, leading to job losses or relocations, ultimately undoing the benefit originally intended.

I do not want to overemphasize the potential downsides; there are many tangible benefits of this program both now and in the long term. The only question is whether we can do better.

Betting On Ourselves

What if, instead of trying to offer subsidies to outsiders, we start investing in ourselves? A tax credit for biotech is a step in that direction, but what could we do with a comparable program for Internet and IT startups? What if we made investment capital available to Maryland businesses as part of a strategy to develop new companies that actually stay here for the long term (and are not susceptible to subsidy bribes from other locales)?

A new program called Invest Maryland has been proposed by Governor Martin O’Malley, and is based on similar programs instituted in other states. The program would make $100 Million in venture capital available to Maryland businesses. Funds would come from tax prepayments made by insurance companies in exchange for tax credits. The theory is that the cost of the tax credits would be exceeded by the benefit in business development provided by the venture investments.

Done properly, this is probably a very sound program. But to be maximally successful, I believe we need to start placing strong bets on information technology startups in particular:

- IT startups are very capital efficient. Thanks to lean startup methodologies, IT startups can get up and running for as little as $50,000 to $150,000 in investment.

- Maryland already has the highest concentration of information technology workers in the world. It’s a strong strategic fit for exactly the same reasons that biotech investment is a good fit.

- To achieve strong returns with early stage investments, it’s often necessary to invest in 150 or more companies. The small capital requirements of IT companies allow for many more investments to be made with less capital, thus increasing the odds of success.

- A large portfolio of seed-stage IT investments can yield internal rates of return of up to 25-30% annually, which is terrifically high. That is in addition to the benefit of building a permanent base of IT businesses in Maryland, and all the job and tax-base benefits that would bring.

- A large number of ventures would, statistically, also have to produce a large number of failures. This culture of continuous endeavor would de-stigmatize failure and allow for repeated teaming and relationship building. Inenvitable losses are not losses, but in fact fertilize the forest floor — building the ecosystem for the long term.

- A culture rich in startups will keep us from exporting our best and brightest to other places, which we do routinely right now.

$10M for IT Startups

As Maryland’s leaders and legislators consider the Invest Maryland initiative, I propose that the state set aside $10M of its $100M fund specifically for IT startups. With that $10M, I propose that Maryland invest in up to 200 seed stage IT firms at anywhere from $50K to $150K per company.

Doing this well will be difficult. However, by partnering with existing entities such as Baltimore Angels and members of the business community, we can make that investment maximally productive. We’d need to figure out the details, but we can’t expect government employees to make these investments on their own without domain expertise. By leveraging the people in the community that want to see these investments occur and who do have appropriate domain expertise, we can dramatically increase the effectiveness of this fund.

And if the initial $10M investment proves effective, we should consider enlarging the program to $25M or higher later. This strategy carries very little risk for the state and would create a stunning worldwide buzz about the vibrancy of the startup culture in Maryland, and would highlight the innovative private-public partnership that sparked it.

Thinking Small

The businesses we routinely cite as our biggest successes — Under Armour, Advertising.com, SafeNet, Sourcefire, Bill Me Later, to name a few — all came about as home-grown successes. They are not here because we brought them here from someplace else. They’re here because they were grown here from scratch, by people who love it here.

If we start now, placing a large number of bets on our brilliant citizenry, we will do something remarkable: we’ll launch a virtuous cycle of entrepreneurship — the opposite of the kind of downward spiral associated with the rust belt era.

Instead of the simplistic “causal logic” associated with “big” economic development, we’ll be using the logic of entrepreneurial “effectuation,” of the kind promoted by entrepreneurship researcher Dr. Saras Sarasvathy.

It is the combined effects of many people pursuing entrepreneurship that will lead us someplace extraordinary. Suddenly, Baltimore (and Maryland) will become the cover story on the airline magazine — the “hot” place to be. One (or ten) corporate headquarters relocations will never do that, because it won’t bring about endemic entrepreneurship in the culture.

Making lots of small bets instead of fewer “big” bets makes government nervous. Everyone wants to be seen as someone who accomplishes something big, and with short gubernatorial terms, it’s tough to get ramped up with plans that might take 10 or 12 years to realize. But that’s exactly what’s needed.

We need to resist the temptation to focus solely on big development, and instead bet on the tiny startups. The big wins will come when these firms flower, and the ecosystem that gave them life comes into its own. Yes, that might happen on someone else’s watch — but it’s still the right thing to do.

A recent report from the Kauffman Foundation proclaims, “Job Growth in U.S. Driven Entirely by Startups.” If this is the case, Lord knows we could use a lot more startups. If we want new jobs — and not jobs poached from other states at great expense and flight risk — the only logical choice is to focus on creating new startups.

And if solid returns of 25-30% can be realized on a large portfolio of startups, shouldn’t we drop almost everything else and focus only on that?

The first state that adopts this strategy will be sowing the seeds of an incredible, dynamic culture of entrepreneurship. Is Maryland ready to take the challenge?

May 16th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, trends

The American educational system deadens the soul and fuels suburban sprawl. It is designed as a linear progression, which means most people’s experience runs something like this:

- Proceed through grades K-12; which is mostly boring and a waste of time.

- Attend four years of college; optionally attend graduate/law/med school.

- Get a job; live in the city; party.

- Marry someone you met in college or at your job.

- Have a kid; promptly freak out about safety and schools.

- Move to a soulless place in the suburbs; send your kids to a shitty public school.

- Live a life of quiet desperation, commuting at least 45 minutes/day to a job you hate, in expectation of advancement.

- Retire; dispose of any remaining savings.

- Die — expensively.

Hate to put it so starkly, but this is what we’ve got going on, and it’s time we address it head-on.

This pattern, which if you are honest with yourself, you will recognize as entirely accurate, is a byproduct of the design of our educational system.

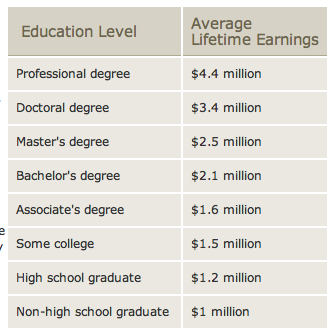

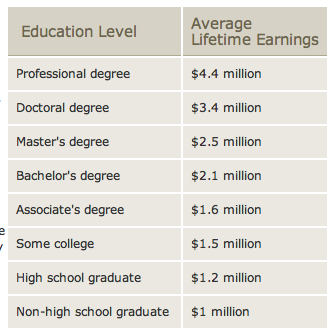

The unrelenting message is, “If you don’t go to college, you won’t be successful.” Sometimes this is offered as the empirical argument, “College graduates earn more.” Check out this bogus piece of propaganda:

But what if those earnings are not caused by being a college graduate, but are merely a symptom of being the sort of person (socioeconomically speaking) who went to college? People who come from successful socioeconomic backgrounds are simply more likely to earn more in life than those who do not.

There’s no doubt that everyone is different; not everyone is suited for the same kind of work — thankfully. But western society has perverted that simple beautiful fact — and the questions it prompts about college education — into “Not everyone is cut out for college,” as though college was the pinnacle of achievement, and everybody else has to work on Diesel engines or be a blacksmith. Because mechanics and artists are valuable too.

That line of thinking is the most cynical, evil load of horse-shit to ever fall out of our educational system. Real-life learning is not linear. It can be cyclical and progressive and it takes side-trips, U-turns, mistakes, and apprenticeships to experience everything our humanity offers us.

The notion that a college education is a safety net that people must have in order to avoid a life of destitution, that “it makes it more likely that you will always have a job” is also utterly cynical, and uses fear to scare people into not relying on themselves. Young people should be confident and self-reliant, not told that they will fail.

And for far too many students, college is actually spent doing work that should have been done in high school — remedial math and writing. So, the dire warnings about the need for college actually become self-fulfilling: Johnny and Daniqua truly can’t get a job if they can’t read and write and do math. See? You need college.

An Education Thought Experiment

I do not pretend to have “solutions” for all that ails our educational system. But as a design thinker, I do believe that if our current educational system produces the pattern of living I noted above, then a different educational system could produce very different patterns of living — ones which are more likely to lead to individual happiness and self-actualization.

If we had an educational system based on apprenticeship, then more people could learn skills and ideas from actual practitioners in the real world. If we gave educational credit to people who start businesses or non-profit organizations, and connected them to mentors who could help them make those businesses successful, then we would spread real-world knowledge about how to affect the world through entrepreneurship.

If more people were comfortable with entrepreneurship, then they would be more apt to find market opportunities, which can effect social change and generate wealth. If education was more about empowering people with ideas and best practices, instead of giving them the paper credentials needed to appear qualified for a particular job, it would celebrate sharing ideas, rather than minimizing the effort required to get the degree. (My least favorite question: “Will that be on the test?”)

Ideally, the whole idea of “the degree” should fade into the background. Self-actualized people are defined by their accomplishments. A degree should be nothing more than an indication that you have earned a certain number credits in a particular area of study.

If the educational system were to be re-made along these lines, the whole focus on “job” as the endgame would shift.

“A sturdy lad from New Hampshire or Vermont, who in turn tries all the professions, who teams it, farms it, peddles, keeps a school, preaches, edits a newspaper, goes to Congress, buys a township, and so forth, in successive years, and always, like a cat, falls on his feet, is worth a hundred of these city dolls. He walks abreast with his days, and feels no shame in not ‘studying a profession,’ for he does not postpone his life, but lives already. He has not one chance, but a hundred chances.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self Reliance, 1841

And so if the focus comes to be on living, as Emerson suggested it should be, and not simply on obtaining the job (on the back of the dubious credential of the degree), then the single family home in the suburb becomes unworkable, for the mortgage and the routine of the car commute go hand-in-hand with the job. They are isolating and brittle, and do not offer the self-actualized entrepreneur the opportunity to meet people, try new ideas, and affect the world around them.

The job holder becomes accustomed to the idea that the world is static and cannot be changed through their own action; their stance is reactive. The city is broken, therefore I will live in the suburbs. The property taxes in the suburbs are lower, so I will choose the less expensive option.

Entrepreneurial people believe the world is plastic and can be changed — creating wealth in the process. But our current system does not produce entrepreneurial people.

Break Out of What’s “Normal”

It may be a while before we can develop new educational systems that produce new kinds of life patterns.

But you can break out now. You’ve had that power all along. I’m not suggesting you drop out.

But I will say this: in my own case, I grew up in the suburbs, went to an expensive suburban private high-school — which I hated — where I got good grades and was voted most likely to succeed.

I started a retail computer store and mail order company in eleventh grade. I went to Johns Hopkins at 17, while still operating my retail business. Again, I did well in classes, but had to struggle to succeed. And no one in the entire Hopkins universe could make sense of my entrepreneurial aspirations. It was an aberration.

I dropped out of college as a sophomore, focused on my business, pivoted to become an Internet service provider in 1995, and managed to attend enough night liberal arts classes at Hopkins to graduate with a liberal arts degree in 1996. This shut my parents up and checked off a box.

I also learned a lot. About science. About math. About philosophy, literature, and art. And I cherish that knowledge to this day.

But I ask: why did it have to be so painful and waste so much of my time? Why was there no way to incorporate that kind of learning into my development as an entrepreneur? Why was there no way to combine classical learning with an entrepreneurial worldview?

Because university culture is not entrepreneurial. And I’m sorry, universities can talk about entrepreneurship and changing the world all they like, but it is incoherent to have a tenured professor teaching someone about entrepreneurship. Sorry, just doesn’t add up for me. Dress it up in a rabbit suit and make it part of any kind of MBA program you like; it’s a farce. Entrepreneurship education is experiential.

I had kids in my mid-twenties and now have moved from the suburbs to the city because it’s bike-able and time efficient. And I want to show my kids, now ten and twelve, that change is possible in cities. I believe deeply in the competitive advantage our cities provide, and I intend, with your help, to make Baltimore a shining example of that advantage.

I don’t suggest that I did everything right or recommend you do the same things. But I did choose to break out of the pattern. And you can too.

Maybe if enough people do, we can build the new educational approaches that we most certainly need in the 21st century. This world requires that we unlock all available genius.