Entries Tagged 'philosophy' ↓

November 7th, 2009 — art, baltimore, business, design, geography, philosophy, trends

In 1983 at age 12, I became drawn to the design and tech culture of San Francisco. By that time I was already deeply involved in computers and the other tech of the day, and had been reading every issue of BYTE Magazine cover-to-cover when it arrived in our mailbox after school.

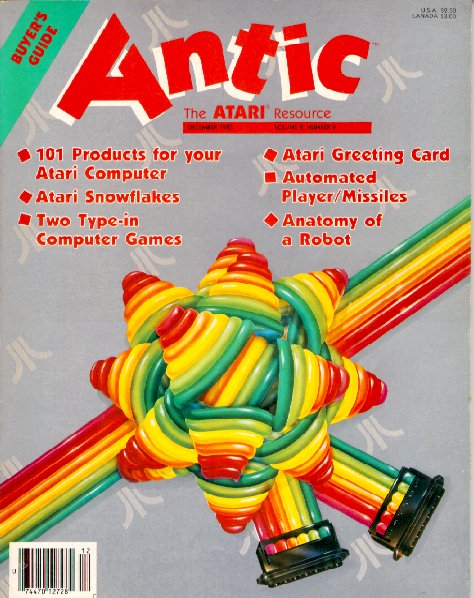

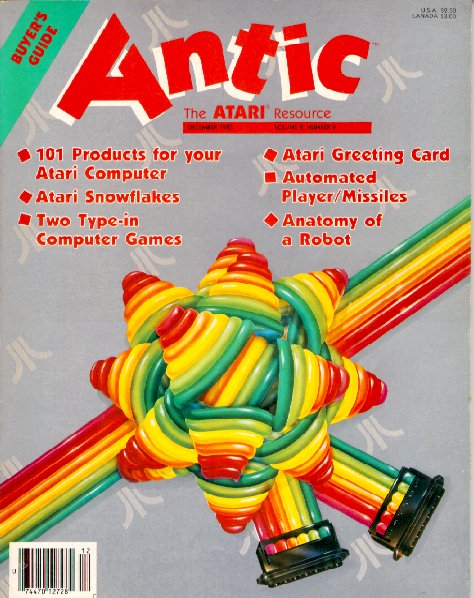

BYTE was produced in New Hampshire and had a scholarly tone; still, the emerging world of computing was breathlessly covered, and offered a sense of endless possibility. But it was Antic magazine (a specialty computing magazine for Atari computers), specifically the December 1983 “Buyer’s Guide” issue that really caught my eye.

The design was colorful and imaginative, with beautiful typography, and the magazine was full of amazing ideas and products which I was sure would launch me on my way to unlimited exploration. I devoured the magazine cover to cover, but I never realized just how much I was soaking up its design ethos. Colorful, playful, and bold, this was not the wry, academic BYTE. It was combining the substance of tech with the emerging design scene in San Francisco, and it resonated with me profoundly.

In 1985, I got a job at a local computer store doing what I loved: selling computers and software and, yes, copies of Antic magazine. In 1986, I started my own computer and software sales company, Toad Computers. In 1989, months after graduating from high school, I had the chance to visit Antic Magazine — this time as an advertiser.

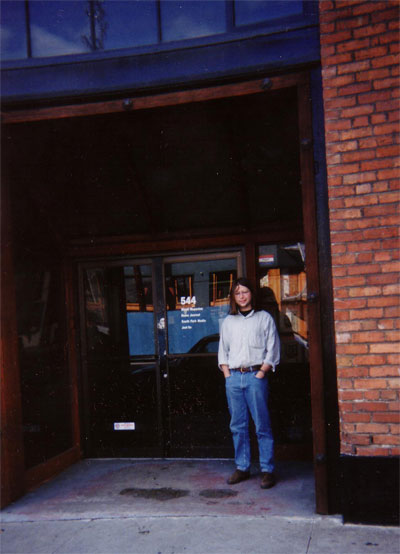

This was my first trip to San Francisco and I visited Antic at their loft office, located at 544 Second Street, right in the heart of the city’s SOMA district. But this was SOMA before it was the SOMA we know now as the home of so many startup tech companies. Beat up and edgy, the open-air second floor office had high-beamed ceilings and gave a sense of history and limitless potential. I was smitten with the city and with valley tech culture – I also visited Atari’s headquarters in Sunnyvale that trip – and absorbed all that I saw.

Later in 1993, I was twenty-one and searching for new things to explore. Toad Computers was doing well but I knew that it would have to change and grow to survive. Atari was having tough times. Antic magazine had folded. To advertise effectively we were sending out massive catalog mailings, featuring 56 page catalogs that I personally designed – very much in the visual style of Antic magazine.

Someone had told me about a new magazine called Wired. I picked up a copy and was immediately struck with its sense of visual design and its aura of infinite possibility through the combination of design and tech. Again, I ingested every word, photo, and illustration in each issue. In early 1994, I noticed an ad that indicated that Wired – this tiny publishing startup – was looking for a circulation manager. I was entranced at the possibility. With my background in direct marketing and managing big catalog mailing lists, I thought this might be an opportunity for me.

In February 1994, I booked a trip to San Francisco to talk to my kindred spirits at Wired about the possibility of working there. I also became entranced with the Internet and its possibilities at this time, and for several days before my trip to San Francisco, I worked feverishly to write an article for Wired about how the Internet – when it became fully developed and evolved – could become a kind of real-time Jungian web of knowledge that acted like a global brain cheap kamagra oral jelly uk. I theorized that the Internet could become a kind of collective consciousness that enabled humanity’s genius to be available to everyone all the time. I predicted online banking, shopping, and video chat and made illustrations to show how these things would work.

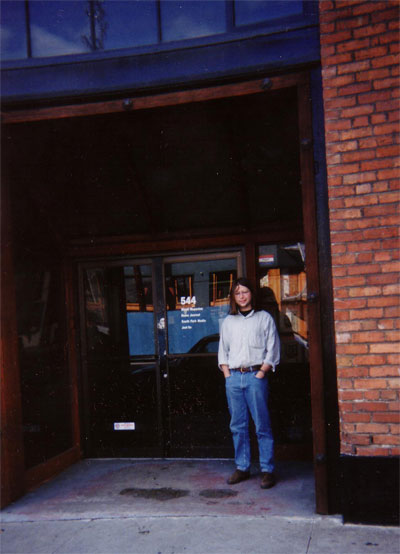

Me, with long hair, at Wired HQ in February 1994

Of course, the simple things were not hard to predict at that time, though they were still a few years off. But my central thesis about Jungian synchronicity was just too wacko to print in 1994. And to be fair, I had cobbled the article together in just a couple of days, had worked in ample quotes from Marshall McLuhan and Carl Jung, and had interviewed no one. My thesis may have been strong, but the piece would have benefited from some interviews and editing. But hey, I was inspired and twenty-two.

When I went to Wired’s offices, I was stunned to learn that they were located in the same office that Antic had occupied! The same open air loft office at 544 Second Street. I met with some folks from Wired’s barebones staff. I commented on my perceived sense of Jungian synchronicity — about Antic and Wired sharing the same office space. We talked about job possibilities. I submitted my article.

I didn’t get a job, and they didn’t print my article. To be fair, I wasn’t really ready to move to San Francisco, and I am sure they sensed that. I also wasn’t sure what I wanted. I just knew that I was drawn to this hopeful admixture of design and tech that seemed to emanate, radio-like, from 544 Second St.

In March 2007, two weeks after I had built Twittervision and a week after SXSW launched Twitter onto the early adopter stage, I thought it would be fun to stop by Twitter HQ in San Francisco. I met Biz and Jack and Ev, and was once again amazed to see that something I had been drawn to had come from SOMA; just a few blocks from 544 Second St. And ironically, it is now Twitter and the “Real Time Web” that is beginning to enable the kind of global consciousness that I had predicted in 1994.

This past Thursday at TEDxMidAtlantic (of which I was the lead organizer and curator) in Baltimore, I was struck by the beautiful design of our stage set. (Thanks to Paul Wolman at Feats, Inc. for bringing it together for us!) A simple combination of bookshelves, cut lettering, books, a few objects and blue wash backlighting had combined to produce a gorgeous backdrop for the extraordinary ideas that our speakers would soon be sharing. And I felt at home. I could not go to 544 Second Street and SOMA. Instead, it was my mission to bring it here.

October 26th, 2009 — business, design, economics, philosophy, software, trends

“Disneyland will never be completed. It will continue to grow as long as there is imagination left in the world.” – Walt Disney

Thinking about Eric Ries‘ lean startup methodologies, it occurred to me that Walt Disney pioneered the form in 1955 with the creation of Disneyland. Let’s take a look.

Private Beta: July 17, 1955

Disneyland was officially launched in a private beta in July 1955 to 6,000 guests by invitation only. Unfortunately, those folks shared their invitation links and 22,000 extra guests showed up with forged tickets! Special guests Ronald Reagan and Art Linkletter helped Walt Disney put on a good show that was live-streamed on television.

But the park was anything but a success that first day. Ladies’ heels sunk into the asphalt slurry sidewalks in the hot July sun. A plumbers’ strike meant that only a few water fountains were operational. A gas leak closed several sections of the park.

These setbacks led Disney’s team to refer to this fateful day as Black Sunday. The opening day generated such negative publicity that Disney and his team took special care to invite the press back the next day and in the coming days to see “the real Disneyland” and see things as they had been intended.

But even if things had gone as planned, only 18 attractions were operational those first few days. Tomorrowland had just four attractions and was admittedly incomplete. Several other attractions would open later in 1955 and 1956.

When Disneyland opened in July 1955, it was literally the minimum viable product. With just $5 Million in financing, there was a lot that Walt wanted to put into the park, but there was only so much money and time.

They launched with what they had ready and took the hit for the stuff that was broken. Why? So they could learn from their customers.

Customer Development

Disney listened to his customers. This change log on the site Yesterland.com shows how much stuff opened in 1955 was eliminated or modified over the years.

New rides were added, old ones modified; others became simply obsolete or required updates. The awkward and failure-prone Flying Saucers ride was replaced in 1967 with the Tomorrowland Stage, which was in turn replaced in 1986 with the Magic Eye Theater. The “Rocket to the Moon” became the “Rocket to Mars.” The iconic Matterhorn Bobsleds ride didn’t open until June 1959, nearly four years after the park’s debut!

Disney’s guest relations department has had the benefit of hearing a huge volume of customer feedback – about which attractions people enjoy, which ones they hate, and which ones literally make them sick. With such a powerful mechanism for continually collecting feedback from millions of customers (who take pride in interacting with one of the world’s most prestigious brands), the Disney organization has benefited from a feedback cycle of continuous improvement.

If Disney and his team had gone into “stealth mode” for 55 years, could they ever have produced the park that we see today?

Build On One Success

After Disneyland was successful, and could benefit from a methodology of continuous improvement, they were able to obtain the financing necessary to build Disney World, Epcot, Euro Disneyland, Animal Kingdom, Disney’s California Adventure, and several other projects. You might think of each of these as several products in a portfolio, but they all flowed from the fundamental success of the original and the conviction that it was okay to launch with a halfway-there product in July 1955. They knew that customers would help them find the way forward.

Disneyland has always been the result of the interaction of management and customers to produce an experience that is valuable for its customers and profitable to operate.

Your software business should take the same approach. You don’t know what your customers are going to want. Launch with something workable, even if flawed. Then iterate with continuous improvements after that. Then, you and your customers will be building something valuable together.

Your product should never be completed, as long as there is imagination left in the world!

October 24th, 2009 — art, business, design, economics, philosophy, software, trends

One of the disturbing things we notice as children is that paper money has no inherent value. Why is it that green pieces of paper are accepted in exchange for all manner of goods and services? Because we have all agreed that it should be so.

Mostly, it is because the various sovereign governments whose soil we inhabit have stated that they will accept payment of tax only in these currencies. So we had best have some of it. This demand creates motivation for all of us to work to get at least a minimum amount of it, and many of us would like to have more than a little.

So, we accept this “green lie” as a fact of life. Money makes the world go around, and we’re all playing this game under penalty of deprivation, or incarceration at the worst case.

Waking Up

Just like Neo, we are called to “wake up” and recognize the nature of this system. Socialist-capitalist world governments are a reality that we impose on ourselves; if we can look up and see beyond it, a whole new world opens up.

Currency Is Different from “Money”

Currency, the worthless bits of paper and metal we trade for handy things like food, beer, and fuel works pretty well and we can rest reasonably sure in our ability to use it to survive.

But what about your 401(k)? It’s an illusion. The financial system is engineered to compel you to shuffle the majority of your wealth into ledger accounts that exist only in your mind. And these “account balances” cause you to make all kinds of decisions — whether to eat out tonight, whether to buy a car or a house, whether to overthrow the government — in particular ways. Your behavior is, in a very real way, controlled by how much “money wealth” you perceive you have.

Glitches In The Matrix

When global financial bubbles jitter as they have done in the last 18 months, home values and 401(k) balances can be badly hurt. These downturns in perceived fortune, in a very real way, cause people to modify their behavior. Maybe you won’t eat out, maybe you won’t take that trip, maybe you won’t start a business. Why do you change your behavior when none of this is real?

Political Implications

Historically, governments are overthrown when unemployment reaches a sustained 15-20%. Current Keynesian fiscal policy adopted by the Fed is aimed at having a variety of control mechanisms to stimulate the economy (lower interest rates; bank lending; TARP mechanisms) when unemployment gets out of control.

But, as we have seen, these market interventions usually lead to unintended consequences. It’s been widely stated that the bank and insurance bailouts were “gifts” to firms like Goldman Sachs who disproportionately benefited from “loopholes” in the regulatory climate. You and your children will certainly pay for these mistakes in the form of devalued currency and sustained taxation.

My point here is to emphasize that monetary policy is an instrument of the state which is used to keep the populace in-line. The debates between the left and right over tax policy are pointless when fiat money allows the Federal Reserve to tweak the knobs of reality at will. And as long as you are motivated by money, you are under the control of this system — and the debates of left and right are just distractions to keep the masses busy. Bush? Obama? Who cares. It probably doesn’t matter to your bottom line. If it doesn’t matter to your personal security, why worry about it?

Finding Inherent Value

Do you ever wish you had a real skill? I don’t mean manipulating ideas or paper, but something tangible? Doctors can trade their services for food. Builders could trade their services for future return of garden produce.

What if your 401(k) was simply gone tomorrow? I don’t mean badly eroded, but gone. What would your future look like? What would be left for you if the monetary system — and all of our current economic system — went bust? What would you have left?

I’d argue you have more than you might imagine. You have family, friends, some basic skills, and an ability to trade effort for necessities. Because everyone would be in the same boat, this would be easier than you might imagine (though it would certainly be chaos).

Current social network tools allow you to start building an economy in the form of interpersonal relationships; by sorting people by shared interests and shared inherent motivations, these tools allow people who find meaning in the same things to find each other. And meaning is at the heart of interpersonal exchange.

Do Important Things

If you endeavor to do things that matter — things that help others, things that change the world, things that have meaning — you will accrue amazing awards in interpersonal relationships. People respect leaders. People respect those who make sacrifices for others. If you’re only in it for yourself and your ability to extract imaginary cash from the system, where will you be when the system fails?

“The System’s Gonna Fail”

In the 1972 film Deliverance, Lewis Medlock (Burt Reynolds) makes a case that “the system’s gonna fail.”

Burt Reynolds: “Machines are gonna fail, and the system’s gonna fail… then…”

Jon Voight: “And then what.”

Reynolds: “Then, survival — who has the ability to survive. That’s the game… survival.”

Voight: “And you can’t wait for it to happen, can ya? You can’t wait for it… Well, the system’s done all right by me.”

Reynolds: “Oh, yeah… You got a nice job, got a nice house, a nice wife, a nice kid.”

Voight: “You make that sound rather shitty, Lewis.”

He may be slightly exaggerating the situation, but when you read books like Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (Charles Mackay, 1842 – yes, 1842!) you start to realize that the financial system we have now is only different from those in the past in that we don’t yet know how this one will fail.

That’s right: we just don’t know how this ends, but it will most assuredly end.

Cash as a Symptom of Good Work

If you spend your days creating real change, the distribution platform for your ideas and your work is larger and less expensive than ever before. Do something original and the entire world is your audience. Do something great and the world will want to reward you.

You can accrue massive “whuffie” in interpersonal relationships, but you’ll also very likely accrue a lot of cash if you do work that is both original and inherently valuable.

And since there’s no way of knowing when the system’s gonna fail, it’s best to simply do good work and build strong relationships. Then you’re covered no matter what happens.

You can only master the matrix when you stop playing by its rules. Wake up, Neo.

April 4th, 2009 — business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, software, trends

We teach entrepreneurs that they should pick an idea they are passionate about, work up a business plan, assemble resources and then execute it.

If we think about entrepreneurialism as a kind of gardening, this traditional approach in a sense encourages people to plant monocultures that are extremely vulnerable to disease. Furthermore, who wants a garden with just one kind of plant in it? Lastly, if the “idea” you choose to plant cannot grow well in your location or your climate, or the climate changes, you are left with a failed crop of your monoculture, and little recourse but to bankrupt yourself and start over.

Any gardener will tell you that putting together a good garden requires a kind of “flow” — getting “in the zone” to think about what plants will work where, what plants will complement each other, and how timing and horticultural relationships will play out to produce a garden that is maximally rewarding, whether those rewards are aesthetic or culinary.

Gardeners know what plants are native to their place, which require sun or shade, which are susceptible to parasite damage, and how to combine plants to achieve symbiotic results. They know how tightly certain plants should be planted, which ones need thinning, and which ones must be started as seedlings.

What you rarely see is a skilled gardener go out and plant a monoculture of, say, beets. Beets by themselves require a specialized kind of farming. A certain kind of soil. To really get a lot of beets, you need to apply particular pesticides and take a particular approach. And when the crop matures (assuming your bet on the conditions and climate pay off), you’ve got just one thing: beets. And, let’s face it: it’s pretty easy to get sick of beets.

“Pushing rocks uphill sucks.” – Sisyphus

In Greek mythology, Sisyphus was sentenced to push a boulder up a hill, only to watch it roll back down so he could push it again for all of eternity. This is a decidedly bad gig. Some businesses are like this too, and too many well-meaning, intelligent entrepreneurs spend time on these kind of Sisyphean enterprises – consuming a lot of precious resources and never getting traction.

In business, there are rocks to push sometimes: hard work is always part of doing something worthwhile. But successful businesses always reach the summit and get to watch the rock roll down the other side.

This is when business is fun. The world seems to love what you’re doing. People are clamoring to work for and with you, the press thinks you’re great, and the money keeps rolling in. New opportunities and ideas emerge at every turn and the sky seems to be the limit.

Great as these conditions are, they rarely last. Businesses nearly universally reach inflection points where their products fall out of favor or stop fulfilling a market need. They become old news, and seemingly out of nowhere, the business is pushing rocks uphill again – usually to the great surprise of management, investors, and customers.

When you’re pushing rocks uphill, you know it. Everyone knows it. The press remarks on it, and just as when things are going well you seem to be in an upward spiral of success, these conditions seem to dictate a downward spiral of failure. These times can be quite dark. Often, they can be sustained and overcome, until you reach a new summit where conditions have changed so that your boulder can roll freely downhill. But many don’t have the stomach to persist through these dark times. “Business turnaround experts” are really just people who can see what’s necessary to minimize drag and reposition a company to that next summit, where more favorable conditions can prevail again.

Towards a New Entrepreneurship

The old model of entrepreneurship creates arranged marriages between entrepreneurs and ideas, and these marriages often don’t work out. After years of struggle, they often end in disaster, and only in extremely forgiving climates do the entrepreneurs get a chance to even re-marry. Quite often, the entrepreneur decides to become celibate and return to its abusive relationship with The Man, while sometimes the wild-eyed ones manage to persist through a couple more failures before finally hitting upon a success.

According to this article based on a report by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the predicted success rate for first-time entrepreneurs is just 20.9%. That’s a one-in-five shot. Even more telling, the results for experienced entrepreneurs is not much better. Entrepreneurs with a track record of success see a 30.6% success rate on average, while serial entrepreneurs who failed in their prior venture are only successful 22.1% of the time on subsequent ventures. To pick a round number, these data show that about 75% of all startups fail.

Is this the best we can expect from the great capitalist engine? What if we could do better? How that might work?

You Don’t Suck – Your Idea Sucks

The data above tell us that experience doesn’t count for that much. In fact, ostensibly it counts for at most a 9.7% improvement in odds. Not a bad gain, but what if it’s an illusion? If an experienced entrepreneur and a first-time entrepreneur chase the same idea, I’d argue the odds of success are roughly equivalent. The only difference between a first-time and experienced entrepreneurs is that they have a better sense about what ideas to chase — and even that discernment may only count for a 9.7% improvement.

So the advice to all entrepreneurs thus becomes essentially the same: pick ideas that will work in the marketplace and expend resources only on those ideas.

Of course, this is easier said than done. How do you know what ideas will work? How can people try a lot of ideas without bankrupting themselves or running themselves ragged?

Starting a Garden of Ideas

First, we have to accept the fact that as individuals, people are really bad at knowing what ideas will work in the marketplace. This is the primary reason for the 75% failure rate we see amongst entrepreneurs. It’s also the reason why top-down planning failed in the Soviet Union. As a general rule of thumb, assume you know a lot less than you think you do about what ideas will work and what ideas won’t, because you’re likely wrong. So are your friends, your family, your trusted advisors, and other more experienced entrepreneurs.

Start thinking instead about what you want your idea garden to look like. What ideas motivate you, and fill you with a sense of childlike wonder? What ideas give you inner peace and create a sense of aesthetic fulfillment? What higher causes do you aspire to? What causes do you think you can motivate others to rally around? With these questions, you can start to get a sense of what you might start to try in your idea garden.

Resonance

Today, we have tools to test the resonance of ideas with fairly wide audiences — for free. Twitter, Facebook, the web, and other mechanisms allow us to expand our networks to find people to bounce our ideas off of. Start bouncing your ideas — the ideas you’re most passionate about — off of a wider audience. Put out feelers. See what sticks.

This wider audience should consist of at least a few hundred people, ideally, and you will get a sense of what ideas move people by listening to peoples’ reactions. If you don’t have an online audience of a few hundred people yet, start thinking about how to get one. Go to meetups and other events. Follow people online whose opinions you trust. Build up a good-sized audience and listen to what they tell you about your ideas.

Ideas Are Cheap

You may worry that sharing an idea with people will “let it out of the bag” and someone else will “steal it.” You’re not so smart to have come up with an idea that no one else has thought of before. Really — believe that. Look through the US Patent Office site sometime and you’ll get a sense for just how cheap ideas really are.

What you must have that is unique and irreplaceable is the vision, passion, and relationships required to bring your idea to fruition.

But the idea itself — the raw two or three sentences that define your concept — has very little potential by itself. By sharing your idea with others, you can strengthen it. Others can contribute to it, pointing out the places where it’s weak, and repurposing it in ways you never imagined. Don’t be afraid to share your ideas, in whole or in part, so that others can help you bring them to fruition.

It could be that you do not want to put all your cards on the table at once. That’s fine. If your idea can be broken apart and tested amongst audiences that way, that can be a way of making your ideas public without disclosing the entire concept. This can be a valid approach when dealing with concepts that require patent protection. But those ideas are much rarer than you think.

You can expect that you will break down and reassemble your own ideas repeatedly before they make it to the market. It’s quite likely that you’ll combine the “resonant” parts of two ideas into one cohesive concept (CD’s by mail bad, DVD’s by mail good) that resonates in the marketplace. Be willing to play around with your ideas and allow them change over time.

Waiting It Out

One of the reasons the success rate for startups is so low is that we have taught entrepreneurs to set up housekeeping with the first viable idea they encounter. The societal pressure to be doing something (so, what are you up to these days anyway?) is very great and people want to perceive and project themselves as successful.

Idea Gardening is something that we as a society have decided is only a valid occupation for people like Richard Branson or Oprah Winfrey. And even they have specific ongoing successes that they can point to that seem to validate their modi operandi.

Gardening takes time — time for sunlight, for seed, for rain to converge in fecundity. The same is true of Idea Gardening. Patience is required for ideas, people, and resources to converge in a way that releases stored energy. If you’re having to use too much pesticide (lawyering) or fertilizer (cash) to make your idea work, you’re likely going against the forces of nature, and not taking advantage of the energy of the marketplace.

Don’t overextend yourself by sinking resources into the first idea you have that looks to be viable. As a committed gardener, you will have many sprouts and leads that are viable. Put your attention to the ideas that seem to be the strongest, and use all of your available resources to drive multiple ideas forward in parallel. Otherwise you’ll have the kind of fragile and brittle all-beet monoculture that will have a hard time surviving market conditions.

Over time, you will find that there are projects that you need to cull. Often, an idea is just premature for the market. But that doesn’t mean you can’t nurture it and keep it going in some form until conditions are right. Often, that is not a very expensive proposition and if you are passionate, it can be very fruitful in the future.

Sunk Costs

People are suckers for sunk costs; this is the instinct that makes folks want to double down in Vegas to recover their losses. But losses are losses, whether measured in time or in money, and chasing after a failed idea to recover yourself to some perceived baseline is a mistake.

In the past, entrepreneur failure often meant sunk costs in the form of infrastructure and time wasted. These sunk costs could run into the hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars. Entrepreneurs, wanting to perceive themselves as successful, very rarely will walk away from this kind of situation willingly or rationally. Likewise, investors (less often) sometimes fall into the same trap. It’s these kinds of sunk costs that keep good money chasing after bad in countless businesses.

Clearly the only rational thing to do is to stop burning money and move on to something that will work. It’s not your fault it didn’t work out — the market didn’t want what you were selling. So, without pride or prejudice, stop the bleeding and move on. It may be your idea is still viable, but it might be viable for someone else, someplace else, at some different point in time. Put it on ice and return to it then.

The key to avoiding the trap of sunk costs in the Idea Gardening model is to minimize costs until an idea looks to be viable. If you have 10 ideas you’re experimenting with, and 4 show promise, what can you do to put a minimal amount of investment in only those four that will advance them to a stage where you can learn more about their prospects?

After that round, it may be that only two show promise at that moment. What can you do to put a minimal amount of investment in only those two ideas that will advance them? It may be that one of those ideas is really ready to explode and is ready to accept a major investment. Do that. By adopting this methodology, all of your investments will be right-sized and appropriate to advancing your concepts. With the disciplined use of this approach, one could theoretically achieve a 75+% entrepreneurial success rate , rather than a 75% failure rate!

This is an entirely different approach to entrepreneurship. For the software developers out there, this is the agile approach to business. Start small, iterate, and follow the market need. This also means that failures, when they occur, happen quickly. And that is the best thing any entrepreneur could hope for.

Cost Control

Besides for only investing time and money into ideas that have promise, it is now more possible than ever to experiment with concepts for very low costs. Free, open source software like Ruby on Rails, PHP, MySQL, and Linux have made it possible to prototype complex concepts extremely inexpensively. If you know how to code the ideas yourself, you can lower costs even further. An entrepreneur who is also a software developer is uniquely positioned to try out dozens of ideas and let the market decide which ones will work.

Additionally, phone services like Google Voice and various other outsourced business services ranging from PayPal to GetFriday and Amazon Mechanical Turk enable incredible things to be done at rock-bottom prices. Cloud computing resources like Amazon EC2 and S3, and Google’s App Engine allow for fast and affordable scaling of ideas at very reasonable prices.

There has never been a better time to be a technology entrepreneur but many of the same forces help all entrepreneurs keep costs down. You won’t get trapped by sunk costs if they are very low; you will walk away from $10,000 sooner than you will $100,000 or $500,000.

More Thomas Edison than Henry Ford

Many of the great industrial entrepreneurs of the last 100 years have been uniquely positioned — as much by accident as by anything else — to capitalize on emergent trends. Carnegie, Mellon, Fricke, Rockefeller, Henry Ford, Bill Gates, and Steve Jobs, all took advantage of (and helped to create) massive trends that could be pushed through society and thereby capitalized on.

You’re not those guys. The odds of any of us finding some “megatrend” that we can exploit profitably for very long are quite slim.

Look instead to Thomas Edison’s approach.

Edison put himself into the Idea Gardening business. His labs in Menlo Park, New Jersey were a virtual playground for engineers. They generated more than 1,500 patents and went on to form General Electric. He was famously quoted as saying that “Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration,” but this is often misunderstood.

Edison wasn’t saying that entrepreneurship was driven by “hard work” of the Sisyphean kind — no one can sustain that kind of load and be that prolific. Rather, he was suggesting that the hard work of invention lay in hoeing the rows and planting countless seeds of innovation so that, in time, the best ideas could bear fruit and thereby transform the world.

So entrepreneurs, plant your gardens. Give them sun, water, and time. The rest will follow, and you, too, will go on to transform the world.

Many thanks to Bill Mill, Mike Subelsky, Gus Sentementes and Jennifer Troy who thoughtfully reviewed this essay.