Entries Tagged 'geography' ↓

April 4th, 2009 — business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, software, trends

We teach entrepreneurs that they should pick an idea they are passionate about, work up a business plan, assemble resources and then execute it.

If we think about entrepreneurialism as a kind of gardening, this traditional approach in a sense encourages people to plant monocultures that are extremely vulnerable to disease. Furthermore, who wants a garden with just one kind of plant in it? Lastly, if the “idea” you choose to plant cannot grow well in your location or your climate, or the climate changes, you are left with a failed crop of your monoculture, and little recourse but to bankrupt yourself and start over.

Any gardener will tell you that putting together a good garden requires a kind of “flow” — getting “in the zone” to think about what plants will work where, what plants will complement each other, and how timing and horticultural relationships will play out to produce a garden that is maximally rewarding, whether those rewards are aesthetic or culinary.

Gardeners know what plants are native to their place, which require sun or shade, which are susceptible to parasite damage, and how to combine plants to achieve symbiotic results. They know how tightly certain plants should be planted, which ones need thinning, and which ones must be started as seedlings.

What you rarely see is a skilled gardener go out and plant a monoculture of, say, beets. Beets by themselves require a specialized kind of farming. A certain kind of soil. To really get a lot of beets, you need to apply particular pesticides and take a particular approach. And when the crop matures (assuming your bet on the conditions and climate pay off), you’ve got just one thing: beets. And, let’s face it: it’s pretty easy to get sick of beets.

“Pushing rocks uphill sucks.” – Sisyphus

In Greek mythology, Sisyphus was sentenced to push a boulder up a hill, only to watch it roll back down so he could push it again for all of eternity. This is a decidedly bad gig. Some businesses are like this too, and too many well-meaning, intelligent entrepreneurs spend time on these kind of Sisyphean enterprises – consuming a lot of precious resources and never getting traction.

In business, there are rocks to push sometimes: hard work is always part of doing something worthwhile. But successful businesses always reach the summit and get to watch the rock roll down the other side.

This is when business is fun. The world seems to love what you’re doing. People are clamoring to work for and with you, the press thinks you’re great, and the money keeps rolling in. New opportunities and ideas emerge at every turn and the sky seems to be the limit.

Great as these conditions are, they rarely last. Businesses nearly universally reach inflection points where their products fall out of favor or stop fulfilling a market need. They become old news, and seemingly out of nowhere, the business is pushing rocks uphill again – usually to the great surprise of management, investors, and customers.

When you’re pushing rocks uphill, you know it. Everyone knows it. The press remarks on it, and just as when things are going well you seem to be in an upward spiral of success, these conditions seem to dictate a downward spiral of failure. These times can be quite dark. Often, they can be sustained and overcome, until you reach a new summit where conditions have changed so that your boulder can roll freely downhill. But many don’t have the stomach to persist through these dark times. “Business turnaround experts” are really just people who can see what’s necessary to minimize drag and reposition a company to that next summit, where more favorable conditions can prevail again.

Towards a New Entrepreneurship

The old model of entrepreneurship creates arranged marriages between entrepreneurs and ideas, and these marriages often don’t work out. After years of struggle, they often end in disaster, and only in extremely forgiving climates do the entrepreneurs get a chance to even re-marry. Quite often, the entrepreneur decides to become celibate and return to its abusive relationship with The Man, while sometimes the wild-eyed ones manage to persist through a couple more failures before finally hitting upon a success.

According to this article based on a report by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the predicted success rate for first-time entrepreneurs is just 20.9%. That’s a one-in-five shot. Even more telling, the results for experienced entrepreneurs is not much better. Entrepreneurs with a track record of success see a 30.6% success rate on average, while serial entrepreneurs who failed in their prior venture are only successful 22.1% of the time on subsequent ventures. To pick a round number, these data show that about 75% of all startups fail.

Is this the best we can expect from the great capitalist engine? What if we could do better? How that might work?

You Don’t Suck – Your Idea Sucks

The data above tell us that experience doesn’t count for that much. In fact, ostensibly it counts for at most a 9.7% improvement in odds. Not a bad gain, but what if it’s an illusion? If an experienced entrepreneur and a first-time entrepreneur chase the same idea, I’d argue the odds of success are roughly equivalent. The only difference between a first-time and experienced entrepreneurs is that they have a better sense about what ideas to chase — and even that discernment may only count for a 9.7% improvement.

So the advice to all entrepreneurs thus becomes essentially the same: pick ideas that will work in the marketplace and expend resources only on those ideas.

Of course, this is easier said than done. How do you know what ideas will work? How can people try a lot of ideas without bankrupting themselves or running themselves ragged?

Starting a Garden of Ideas

First, we have to accept the fact that as individuals, people are really bad at knowing what ideas will work in the marketplace. This is the primary reason for the 75% failure rate we see amongst entrepreneurs. It’s also the reason why top-down planning failed in the Soviet Union. As a general rule of thumb, assume you know a lot less than you think you do about what ideas will work and what ideas won’t, because you’re likely wrong. So are your friends, your family, your trusted advisors, and other more experienced entrepreneurs.

Start thinking instead about what you want your idea garden to look like. What ideas motivate you, and fill you with a sense of childlike wonder? What ideas give you inner peace and create a sense of aesthetic fulfillment? What higher causes do you aspire to? What causes do you think you can motivate others to rally around? With these questions, you can start to get a sense of what you might start to try in your idea garden.

Resonance

Today, we have tools to test the resonance of ideas with fairly wide audiences — for free. Twitter, Facebook, the web, and other mechanisms allow us to expand our networks to find people to bounce our ideas off of. Start bouncing your ideas — the ideas you’re most passionate about — off of a wider audience. Put out feelers. See what sticks.

This wider audience should consist of at least a few hundred people, ideally, and you will get a sense of what ideas move people by listening to peoples’ reactions. If you don’t have an online audience of a few hundred people yet, start thinking about how to get one. Go to meetups and other events. Follow people online whose opinions you trust. Build up a good-sized audience and listen to what they tell you about your ideas.

Ideas Are Cheap

You may worry that sharing an idea with people will “let it out of the bag” and someone else will “steal it.” You’re not so smart to have come up with an idea that no one else has thought of before. Really — believe that. Look through the US Patent Office site sometime and you’ll get a sense for just how cheap ideas really are.

What you must have that is unique and irreplaceable is the vision, passion, and relationships required to bring your idea to fruition.

But the idea itself — the raw two or three sentences that define your concept — has very little potential by itself. By sharing your idea with others, you can strengthen it. Others can contribute to it, pointing out the places where it’s weak, and repurposing it in ways you never imagined. Don’t be afraid to share your ideas, in whole or in part, so that others can help you bring them to fruition.

It could be that you do not want to put all your cards on the table at once. That’s fine. If your idea can be broken apart and tested amongst audiences that way, that can be a way of making your ideas public without disclosing the entire concept. This can be a valid approach when dealing with concepts that require patent protection. But those ideas are much rarer than you think.

You can expect that you will break down and reassemble your own ideas repeatedly before they make it to the market. It’s quite likely that you’ll combine the “resonant” parts of two ideas into one cohesive concept (CD’s by mail bad, DVD’s by mail good) that resonates in the marketplace. Be willing to play around with your ideas and allow them change over time.

Waiting It Out

One of the reasons the success rate for startups is so low is that we have taught entrepreneurs to set up housekeeping with the first viable idea they encounter. The societal pressure to be doing something (so, what are you up to these days anyway?) is very great and people want to perceive and project themselves as successful.

Idea Gardening is something that we as a society have decided is only a valid occupation for people like Richard Branson or Oprah Winfrey. And even they have specific ongoing successes that they can point to that seem to validate their modi operandi.

Gardening takes time — time for sunlight, for seed, for rain to converge in fecundity. The same is true of Idea Gardening. Patience is required for ideas, people, and resources to converge in a way that releases stored energy. If you’re having to use too much pesticide (lawyering) or fertilizer (cash) to make your idea work, you’re likely going against the forces of nature, and not taking advantage of the energy of the marketplace.

Don’t overextend yourself by sinking resources into the first idea you have that looks to be viable. As a committed gardener, you will have many sprouts and leads that are viable. Put your attention to the ideas that seem to be the strongest, and use all of your available resources to drive multiple ideas forward in parallel. Otherwise you’ll have the kind of fragile and brittle all-beet monoculture that will have a hard time surviving market conditions.

Over time, you will find that there are projects that you need to cull. Often, an idea is just premature for the market. But that doesn’t mean you can’t nurture it and keep it going in some form until conditions are right. Often, that is not a very expensive proposition and if you are passionate, it can be very fruitful in the future.

Sunk Costs

People are suckers for sunk costs; this is the instinct that makes folks want to double down in Vegas to recover their losses. But losses are losses, whether measured in time or in money, and chasing after a failed idea to recover yourself to some perceived baseline is a mistake.

In the past, entrepreneur failure often meant sunk costs in the form of infrastructure and time wasted. These sunk costs could run into the hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars. Entrepreneurs, wanting to perceive themselves as successful, very rarely will walk away from this kind of situation willingly or rationally. Likewise, investors (less often) sometimes fall into the same trap. It’s these kinds of sunk costs that keep good money chasing after bad in countless businesses.

Clearly the only rational thing to do is to stop burning money and move on to something that will work. It’s not your fault it didn’t work out — the market didn’t want what you were selling. So, without pride or prejudice, stop the bleeding and move on. It may be your idea is still viable, but it might be viable for someone else, someplace else, at some different point in time. Put it on ice and return to it then.

The key to avoiding the trap of sunk costs in the Idea Gardening model is to minimize costs until an idea looks to be viable. If you have 10 ideas you’re experimenting with, and 4 show promise, what can you do to put a minimal amount of investment in only those four that will advance them to a stage where you can learn more about their prospects?

After that round, it may be that only two show promise at that moment. What can you do to put a minimal amount of investment in only those two ideas that will advance them? It may be that one of those ideas is really ready to explode and is ready to accept a major investment. Do that. By adopting this methodology, all of your investments will be right-sized and appropriate to advancing your concepts. With the disciplined use of this approach, one could theoretically achieve a 75+% entrepreneurial success rate , rather than a 75% failure rate!

This is an entirely different approach to entrepreneurship. For the software developers out there, this is the agile approach to business. Start small, iterate, and follow the market need. This also means that failures, when they occur, happen quickly. And that is the best thing any entrepreneur could hope for.

Cost Control

Besides for only investing time and money into ideas that have promise, it is now more possible than ever to experiment with concepts for very low costs. Free, open source software like Ruby on Rails, PHP, MySQL, and Linux have made it possible to prototype complex concepts extremely inexpensively. If you know how to code the ideas yourself, you can lower costs even further. An entrepreneur who is also a software developer is uniquely positioned to try out dozens of ideas and let the market decide which ones will work.

Additionally, phone services like Google Voice and various other outsourced business services ranging from PayPal to GetFriday and Amazon Mechanical Turk enable incredible things to be done at rock-bottom prices. Cloud computing resources like Amazon EC2 and S3, and Google’s App Engine allow for fast and affordable scaling of ideas at very reasonable prices.

There has never been a better time to be a technology entrepreneur but many of the same forces help all entrepreneurs keep costs down. You won’t get trapped by sunk costs if they are very low; you will walk away from $10,000 sooner than you will $100,000 or $500,000.

More Thomas Edison than Henry Ford

Many of the great industrial entrepreneurs of the last 100 years have been uniquely positioned — as much by accident as by anything else — to capitalize on emergent trends. Carnegie, Mellon, Fricke, Rockefeller, Henry Ford, Bill Gates, and Steve Jobs, all took advantage of (and helped to create) massive trends that could be pushed through society and thereby capitalized on.

You’re not those guys. The odds of any of us finding some “megatrend” that we can exploit profitably for very long are quite slim.

Look instead to Thomas Edison’s approach.

Edison put himself into the Idea Gardening business. His labs in Menlo Park, New Jersey were a virtual playground for engineers. They generated more than 1,500 patents and went on to form General Electric. He was famously quoted as saying that “Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration,” but this is often misunderstood.

Edison wasn’t saying that entrepreneurship was driven by “hard work” of the Sisyphean kind — no one can sustain that kind of load and be that prolific. Rather, he was suggesting that the hard work of invention lay in hoeing the rows and planting countless seeds of innovation so that, in time, the best ideas could bear fruit and thereby transform the world.

So entrepreneurs, plant your gardens. Give them sun, water, and time. The rest will follow, and you, too, will go on to transform the world.

Many thanks to Bill Mill, Mike Subelsky, Gus Sentementes and Jennifer Troy who thoughtfully reviewed this essay.

March 15th, 2009 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, travel, trends

“When do we all become native to this place? When do we all become indigenous people?” – William McDonough

Ever wonder why America has such trouble with suburban sprawl, highway congestion, and keeping its urban centers viable? It’s a result of how we see “place” relative to other factors in society. We don’t respect it much; it is subservient to education and corporate employment.

For the last 60 years, “success” has meant going to a “good” college or university, getting one or more degrees, and then securing a “good” job. And we have told our children that they need to get good grades and engage in an array extracurricular activities in order to get into those good schools. The logical conclusion is that our children should fear the inverse outcome: not getting the good grades, not going to a good school, and ultimately not securing the good job. So the message is one of struggle: the world requires you to conform to its standards — you, the aspiring student, are expected to make sacrifices in order to be rewarded. And those rewards are held up as the make-or-break difference between the “good life” and an average life as a postal clerk.

And so the deadening chain of sacrifice and compromise begins.

When a promising 16-year old student tells her guidance counselor that she wants to study marine biology, can she really mean it?

When she is answered that she should consider a list of 5 schools, 4 of which are scattered across the country, is this even helpful?

A young person is rarely able to comprehend the specific nature of their vocation, much less make a choice about where they want to live to pursue that alleged vocation. So, what this mechanism really represents is a great geographic randomizer that spews people around the country while racking up student loans, disconnecting people from their indigenous roots and fueling the education industry.

Once the degrees are completed, the job hunt begins. Graduates and corporations engage in bizarre mating rituals, each trying to convince the other that they are the ones who got the better end of their devil’s bargain. And so the newly-minted worker starts to do what the corporation asks. When an “opportunity” comes up in a new city, the worker is enticed to rip up their roots, divorcing them from whatever local connections they have — trading them in for a 10-year thank-you watch, a 4.5% raise and a moving allowance.

A transplanted worker can’t know a new place deeply. Their immediate needs are straightforward and purchased: a house to store their possessions, proximity to shopping, services, and restaurants. If they have or want children, they also want good schools. Of course, good schools are hard to come by, and that scarcity means that the houses with the best schools cost the most money, and so the compromise is made and the choice is made to settle in a place that they necessarily have no connection to. They like it. It’s nice. It solves their need. And they have no idea where they live.

And so they don’t (really, deeply) care about where they live. They don’t care when a new shopping center is built, destroying an ancient stand of trees and filling a stream with runoff. (Oh look, we’re getting an Anthropologie and a P.F. Chang’s — I hear the lettuce wraps are great.)

They don’t care when new roads are built to service the very subdivisions they inhabit, leading to more traffic.

They don’t care when public transportation projects continue to go unfunded, because public transportation would require a 30-year budget process (longer than the attention span than most itinerant residents) and significant urban density.

And they don’t care when the city-centers in their megalopolis rot due to white flight and a failure to invest in urban infrastructure.

Enough.

- People should aspire to grow where they are planted.

- If they cannot grow where they are planted, they should at least plant themselves someplace they can grow.

- What someone does for a living should not necessarily determine where they live.

- Place is not fungible.

Why are so many successful people unhappy? And why are so many “less successful” people completely at peace?

People who have an opportunity to connect to place (to history, to extended family) are often the most at-peace and effective. Mike Rowe (of Discovery Channel’s Dirty Jobs) gave a surprisingly good talk at the EG conference about the meaning of work and what it means to perform the tasks that others in our society will not. In many senses, these are the people who have chosen to commit themselves to a place.

If You Want to be Green, Choose a Place to Love

If you really want to do good for your environment, it is not enough to commit yourself to unbleached paper towels and driving a Prius. In fact, both of those things represent environmental harm and disconnectedness. Paper towels? Spill less stuff, and use washable towels. A Prius? The energy required to build and dispose of its batteries is immense. An inexpensive high-mileage gasoline vehicle that you keep for years and barely use does much less harm than a Prius you drive 75 miles every day for 7 years.

The things that lead to the most efficient behaviors (commuting less, sharing resources, maximizing time efficiency) all derive directly from maximizing the relationship to the place where you live.

And so the ways you can make the most difference — and be the most green — have nothing to do with what you consume — they are derived from the design of your life. Is your life designed in such a way that you can become indigenous?

When you become indigenous to a place, you enable it in all kinds of new ways. Engagement is contagious and leads people to recognize themselves in others — and in you. Where before, kids were encouraged to follow their hearts by going to MIT (and thus launching the great chain of place-divorce), they realize they can follow their hearts by being a part of the schools (and culture) in their own backyard — which offer a rich, world-class experience. And so they stay. And they care about their cities, parks, and forests. And they go on to enrich their cultural institutions, entrepreneurial climate, and their urban centers. If you don’t think you have the kind of world-class culture you want to see in your backyard, start building it now by reaching out to others who want to see the same thing.

All of this leads to the most efficient use of resources in the place where you live. Isn’t that green?

How Do You Become Indigenous to Your Place?

Commit yourself to it. Attend events and meetups that you find interesting. Start events and meetups that you would like to see. Reach out to the bright minds in your own backyard. They are there, but they don’t know you are yet. Say hello. Work on ideas and projects that matter and have consequences. Start a business. Help someone. Be a mentor. Read history, and understand why your place is the way it is.

Place is not just another consumer choice. Place provides context for human interaction; it is the basis of our humanity. Only through connectedness to place do we enable the fullest range of human expression and of human being.

As we enter into a new economic cycle (I’ll stop short of calling it a new era), it is clear that economic activity based on flows and cycles is going to receive more attention than old school approaches of resource-rape and infinite expansion through leverage and buried externalities. For businesses based on closed cycles to maximize profits, they need to limit transportation of inputs and wastes, and that points towards fundamentally local and regional businesses. Local production and consumption is an inescapable imperative of the emerging business cycle.

If you have children, teach them about the place where they live. Talk about the future in ways that help them understand how (and why) they might make a life where you live now, without locking them down or sounding creepy — just make it a viable option. Start thinking about your family home as a family seat, not just a house that you buy or sell as an investment. If you’re not living in a home you would want to pass on to your children (or which they would not want), consider making that final move to a place that you may keep for a long time.

For some, keeping the same residence (be it apartment or house) is not always an option, or sensible. So if you can’t connect to a particular piece of real-estate, what can you do to connect yourself to a city?

In either case, you can’t become indigenous to a place without a multi-generational mindset.

The Constraint of Place

Anyone who does anything creative will tell you that constraints actually improve your work. All of this talk about becoming indigenous and attaching multiple generations to a place can sound confining and perhaps even suffocating — or worse yet anti-American (think about why that is for a minute). But, as a constraint it may actually be freeing.

Isn’t it central to our capitalist-consumer culture that each generation should be free to make its own choices about where to live and why? Why should our children be burdened by our choice of house and where to live? Isn’t it only a burden if it isn’t a very good choice?

But what if a constraint to place was something that actually enabled creativity? What if the choice of one generation was a reasonable choice for the next? If you were going to keep a home in your family for 10 generations, what kind of home would that be? Why don’t you live in it now?

This is not to say that it’s not acceptable to move if you need to move, or to even enjoy multiple places. A 19th-century worldview, of wintering in one place and summering in another, can make a lot of sense, assuming you fully connect to both places. Become indigenous to two places rather than a consumer (and destroyer) of many.

Conferences represent some of the worst excess and abuse (and neglect) of place. Why travel to a multitude of destinations to stay in hotels, eat bad meals, and talk to people who are only marginally better than the people you would find in your own backyard (if you’d only take the time to locate and develop them). Yes, conferences represent the only forum to connect with certain people, and it will be a while before the activity in your backyard can be as rich, etc. Blah. If you fully engage with the people in your own backyard, your appetite to travel to conferences will be substantially lessened.

The Future Is Local

I am not the first to suggest that the economy of the future will have a big local component. Certainly that is true. However, we’re not just talking about switching to buying local garlic, squash, and milk here. Just as you can’t take and pile “new media” ways of doing business onto the newspaper industry, we can’t expect to reorient our economy to local production cycles without also adopting very different sets of behaviors.

I believe that new communications and organizing tools will cause these fundamental transformations:

- Restaurants will morph into dinner parties and gatherings

- Reverence for MIT, Harvard and Wharton will morph into localized study groups and self-education

- Desire for more possessions will morph into “conspicuous asceticism”

- Cars will be stigmatized as a mode of transport and, among those who care, valued as design objects only

- National/Global Conferences will be seen as carbon-tacky and time inefficient (a day lost traveling in each direction? why?)

- 7-14 day Vacations will become less common than poly-local living (these are the 2-3 places I want to live in)

- Hotels will fall out of favor relative to house-swapping and “couchsurfing”

- Cities will receive continued (and renewed) attention as McMansion-laden suburbs deteriorate and are stigmatized

- Homeschooling will emerge among progressive communities (not just the religious right) as a way of avoiding the dysfunctional public school system

- Public Schools will see new levels of engagement from their communities, as people are better able to communicate and organize outside of traditional PTA-like structures

- Food will be a focus of local living, with community supported agriculture and Internet enabled food-swaps

- Coworking will continue to develop as a way for people to connect and collaborate locally

- Local Conferences will flourish as people build critical mass around shared interests using network tools

- Mass produced consumer goods will see a lessening of popularity relative to artisan-produced goods with local connections

- Consumption will give way to communion, and participation in cycles of use

- Tools like iTunes U and Google Books will enable a lifetime of personal learning and one-on-one sharing

I believe we are already seeing the effects of most of these forces — some more than others. But this is not hippie pie-in-the-sky, smoking-weed-in-the-commune stuff. Notice all of this is free of ideology and any trace of the culture wars. These are facts and a simple observation and meditation on what’s happening in society already today.

And notice that each and every one of these forces is rooted first in a connection to place. These things are only enabled when you combine current people-connecting technologies (networking tools) with a specific location. Once these new ways of being start to supplant the old structures (which is going to happen, no matter how you feel about it) they are going to be hard to reverse because they represent fundamentally more stable ways of being.

Once people do finally become indigenous to their place, why and when would that stop?

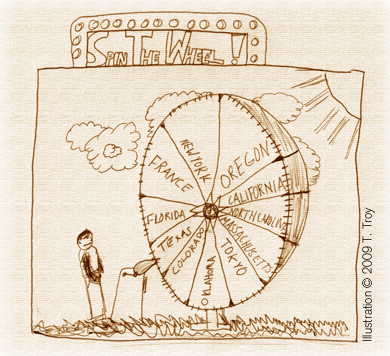

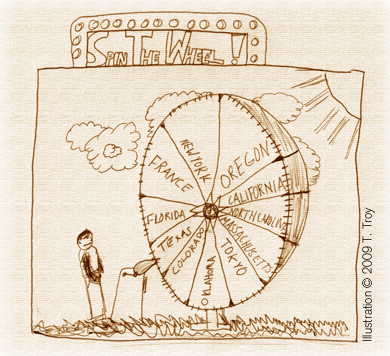

Thank you to my son Thomas for providing the illustration for the very reasonable price of $4.

January 16th, 2009 — art, design, economics, geography, philosophy

A few weeks ago, my wife picked up a book called The Written Suburb at a Greenwich Village used bookshop about Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and how it was an invented, postmodern place, designed to become a mythological homeland of the American realist movement.

As the area was home to painters like Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, and Andrew Wyeth, its history was certainly intertwined with that of American art. The Brandywine River Museum has done a fine job selling itself as the First Church of Delaware Valley Realism and enhancing the myth of Brandywine River as a seat of not just Realism but also of the Real.

As a teenager, I had visited the Brandywine River Museum, and when pressed to write a paper for an art class, I chose to write about the work of Maxfield Parrish, the prolific American illustrator whose work is featured there. I was enchanted by his technical method, which employed multilayer transparencies and unusual materials, but my teacher disputed that his stuff was really “art” and undoubtedly had wished I’d chosen to write about Picasso or Millet — somebody “real.”

With the news of the death of Andrew Wyeth, the whole question of whether the Brandywine River school really produced “art” is back in the news again. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York refused to show his “Helga” paintings on the grounds that they were not, or at least weren’t very good.

The Museum of Modern Art keeps Andrew Wyeth’s most famous work Christina’s World (1949) in a back corner, and it’s always fun to watch people discover its presence. They stumble upon it, and are surprised at how it moves them. As an icon, they are completely ready for it to be trite and clichéd, but in person it still seems to catch people up.

Art purists would say that the only valid art is work that’s done for art’s sake alone: without guile, without intention to build an audience, without regard to populism. Arguably, only art that fits this definition can advance what’s been done before it in the same vein: populism and intellectual progress usually don’t mix.

However, another definition of art is any work that conveys emotion, and on this score, the Wyeths and the Brandywine River School perform well enough to merit attention. That 200 million people can name Wyeth as one of their favorite artists shows his communication has been effective, however invented or populist it may be.

The intersection between art, populism, and commerce is an interesting place to poke around. Here are the seams of our culture, where values, money, and progress bang up against each other.

The Brandywine River Museum touts the artistic authenticity of an invented place, and the Wyeths, Pyle, and Parrish are all promoted as invented artists, designed to insure the flow of tourist dollars into Chadds Ford and Kennett Square — beautiful places, to be sure, and if you squint you can convince yourself the place conveys the feelings the art is trying to make you feel — especially at this time of year, when the browns, greys, white and cold look and feel just like a Wyeth landscape.

But in the end, that’s a leap of faith on the part of the viewer. Sometimes art requires the viewer to become complicit in its own invention.