Entries Tagged 'economics' ↓

November 19th, 2012 — design, economics, geography, politics, trends, visualization

The 2012 election demonstrated what many people could have guessed: rural states voted for Romney while densely populated states voted for Obama.

Many have offered explanations — everything from the presence of top universities in cities, to the prevalence of immigrant and African American populations. Perhaps the Republicans should consider running a Hispanic or African American candidate in 2016; but will that really help? Is identity the issue, or is it more about values?

Or is something more basic at work? Studying election results county by county, a stunning pattern emerges.

Population Density: the Key to Voting Behavior?

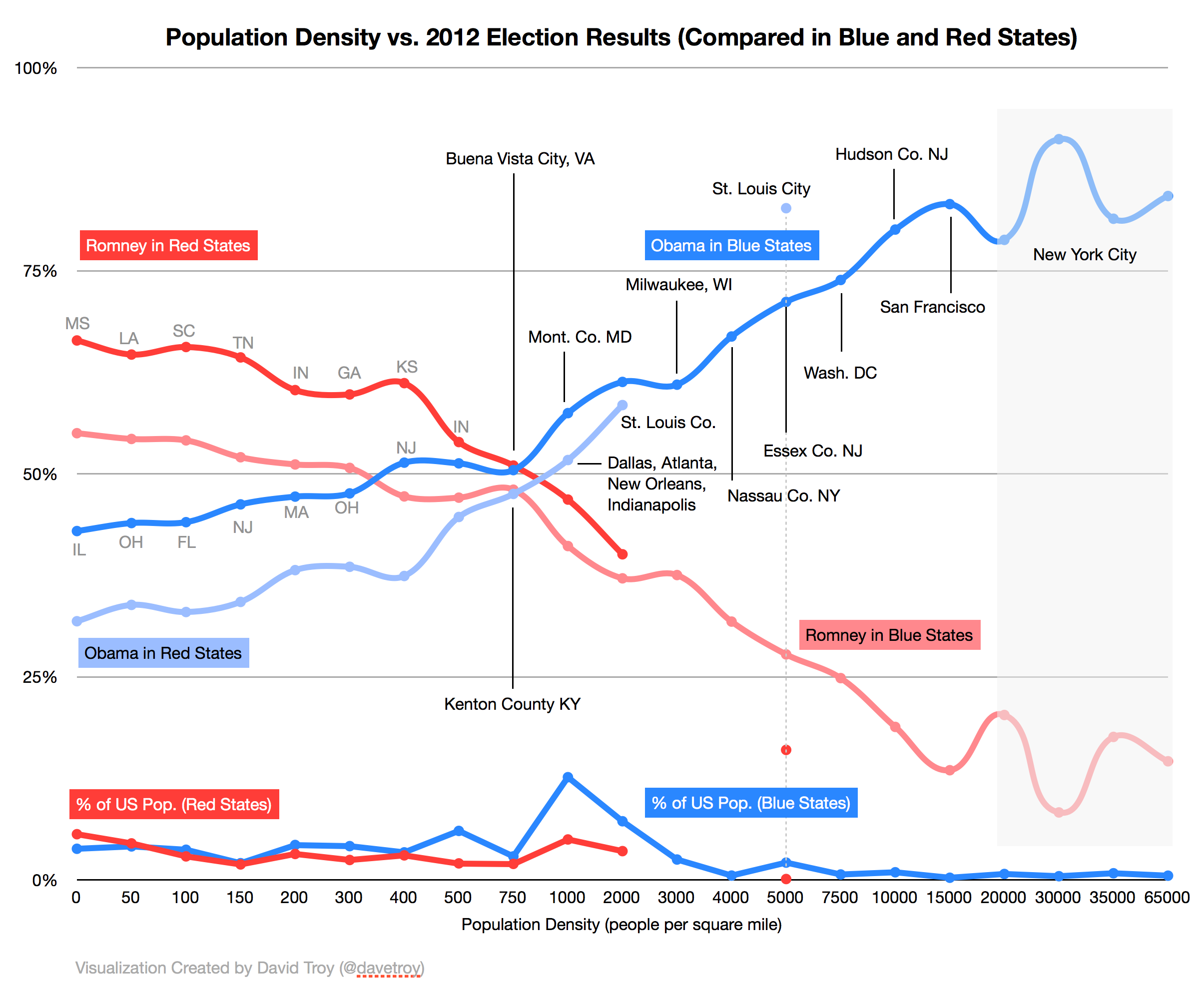

Curious about the correlation between population density and voting behavior, I began with analyzing the election results from the least and most dense counties and county equivalents. 98% of the 50 most dense counties voted Obama. 98% of the 50 least dense counties voted for Romney.

This could not be a coincidence. Furthermore, if the most dense places voted overwhelmingly for Obama, and the least dense places voted overwhelmingly for Romney, then there must be a crossover point: a population density above which Americans would switch from voting Republican to voting Democratic.

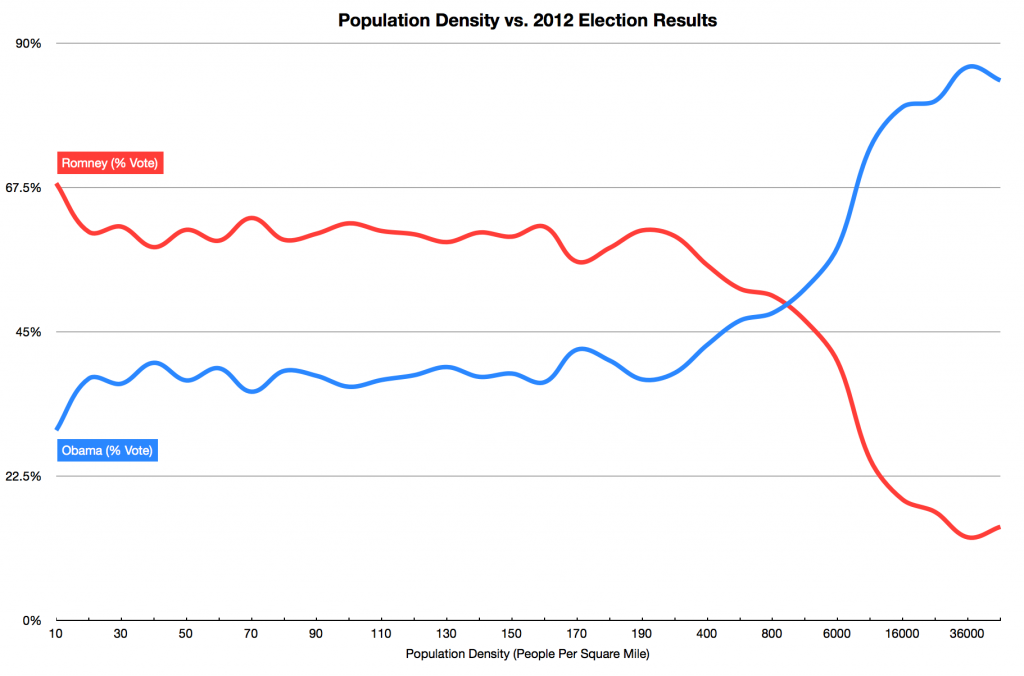

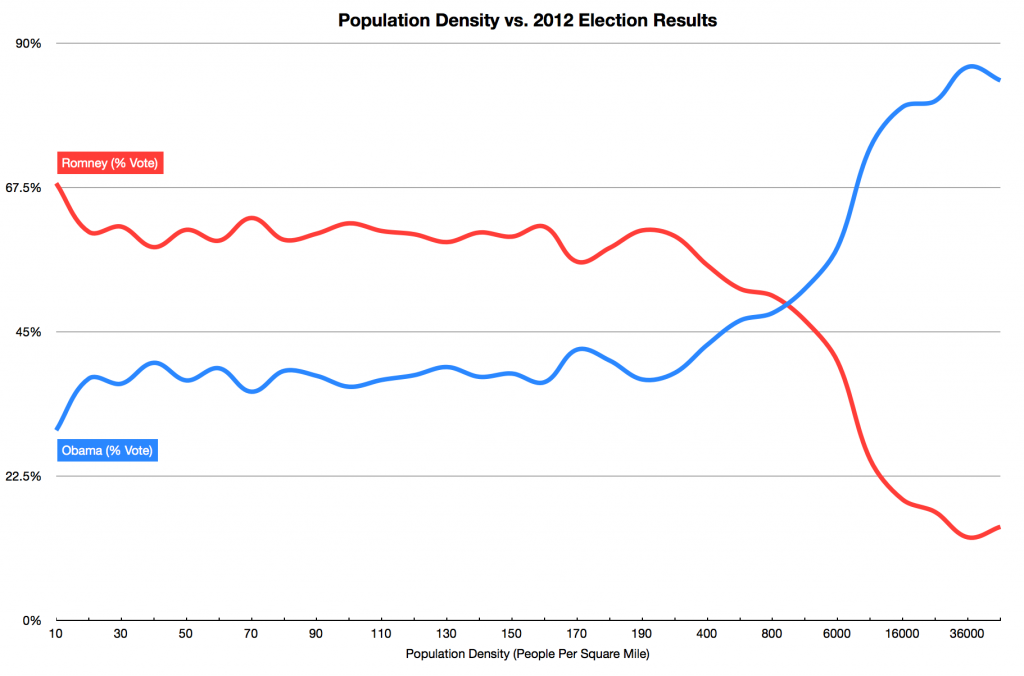

So I normalized and graphed the data, and there is a clear crossover point.

At about 800 people per square mile, people switch from voting primarily Republican to voting primarily Democratic. Put another way, below 800 people per square mile, there is a 66% chance that you voted Republican. Above 800 people per square mile, there is a 66% chance that you voted Democrat. A 66% preference is a clear, dominant majority.

So are progressive political attitudes a function of population density? And does the trend hold true in both red and blue states?

Red States and Blue States

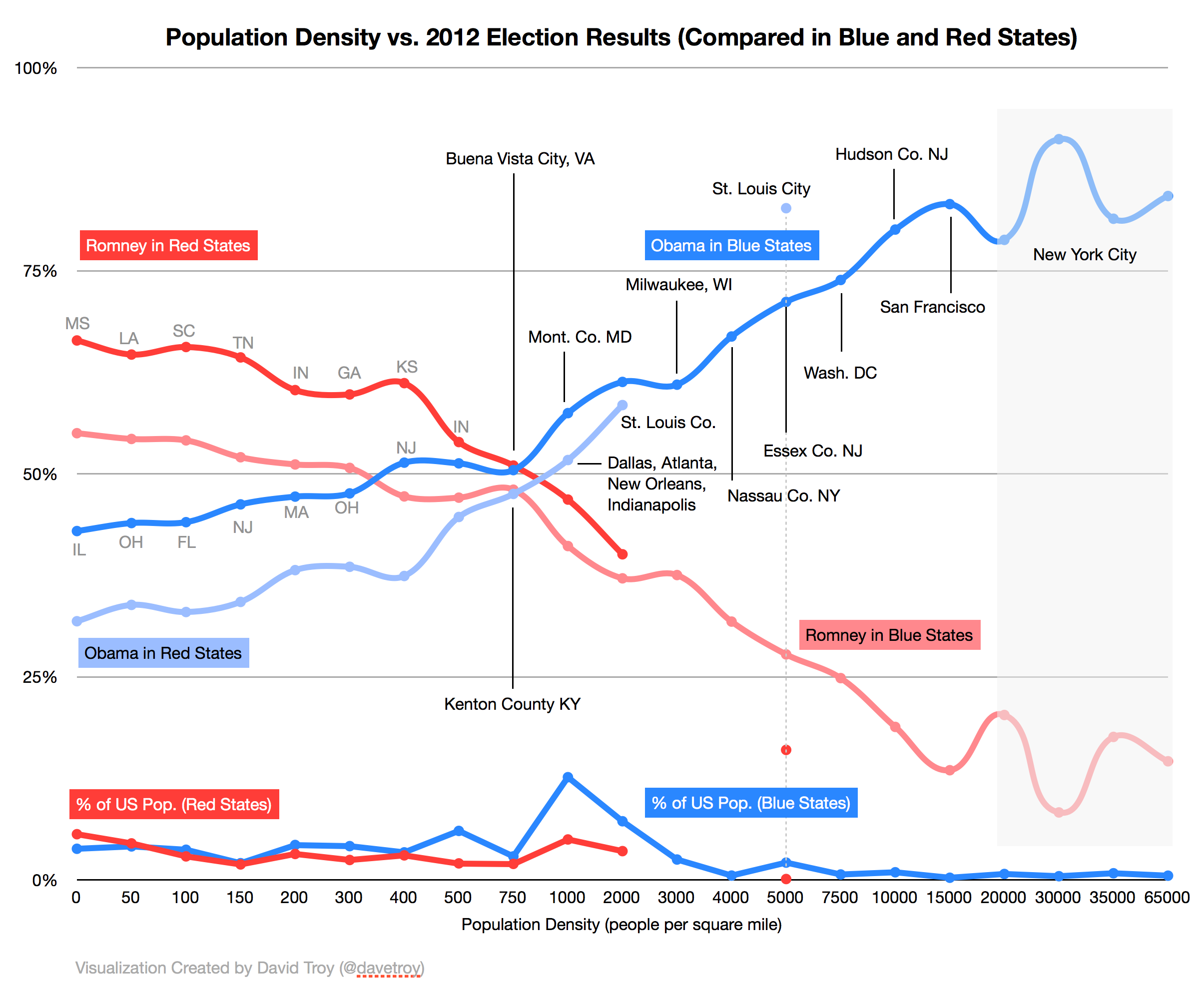

Separating the results from red states and blue states, we can see that while each has a slight preference for their ultimate candidate of choice, on a local level voting behavior is still directly correlated to population density.

Studying this graph, two important facts are revealed. First, there are very few cities in red states. Second, the few dense cities that do exist in red states voted overwhelmingly democratic.

Atlanta, New Orleans, St. Louis, Dallas, and Indianapolis are all in red states — and they all voted blue. And there are no true “cities” in red states that voted red. The only cities in red states that didn’t vote blue were Salt Lake City and Oklahoma City. And by global standards, they are not really cities — each has population density (about 1,000/sq. mi.) less than suburban Maryland (about 1,500/sq. mi.).

Historically, one can argue that red states have disproportionately affected election results by delivering a material number of electoral votes.

Red states simply run out of population at about 2,000 people per square mile. St. Louis is the only city that exceeds that density in a red state. It voted overwhelmingly Democratic (82.7%). In contrast, blue states contain all of the country’s biggest and densest cities: Washington DC, New York City, San Francisco, Baltimore, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, Boston, etc.

Red States Are Just Underdeveloped Blue States

As cities continue to grow in red states, those cities will become more blue, and ultimately, those states will become more purple, and then blue. The Republican party says it’s about growth and prosperity; the best way to achieve that in red states is through the growth of cities.

If you follow the red state trend lines, you can clearly see that any dense, fast-growing cities that might emerge in red states will be very likely to vote blue. The few that do already exist already vote blue. How would these new cities be different and cause them to vote red?

Red state voters generally prefer low-density housing, prefer to drive cars, and are sensitive to gas prices. Once population density gets to a certain level, behaviors switch: high-density housing is the norm, public transit becomes more common, and gas use (and price sensitivity) drops.

Red state values are simply incompatible with density.

Cities Are the Future

Globally, cities are growing rapidly as people move from rural to urban areas in search of opportunity. By 2030 it’s estimated that cities will grow by 590,000 square miles and add an additional 1.47 billion people.

Only subsidized suburban housing and fuel prices are insulating the United States from this global trend, and even with these artificial bulwarks, there is no good reason to think that America’s future lies in low-density development.

Density is efficient. Density produces maximum economic output. An America that is not built fundamentally on density and efficiency is not competitive or sustainable. And a Republican party that requires America to grow inefficiently will become extinct.

While the Republican party is retooling in the desert, it should carefully consider whether its primary issue is identity politics or whether its platform is simply not compatible with the global urban future. If that’s the case, an Hispanic candidate running on the same old Republican platform will simply not resonate. The Republican party must develop a city-friendly platform to survive.

Cities are the future and we need candidates from both parties that understand that reality.

The next question: why does population density produce these voting behaviors? Is the relationship causal or correlated? Probably both. I’ll explore this in my next post.

Data Source: US Census 2010 (population density by counties); Politico.com election 2012 results by County.

December 21st, 2011 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, trends

There’s been an explosion of interest in new “startup accelerators,” incubation, coworking, startup funding, and new-manufacturing efforts in Baltimore in the last few months; unfortunately this appears to say less about Baltimore than it does about the growth in interest in these efforts worldwide.

Here’s a list of some efforts in this space:

- “Accelerate Baltimore” at ETC Baltimore

- Accelerator led by Cangialosi and Lane

- ETC Baltimore itself (Canton and 33rd street)

- Baltimore Node, Hackerspace on North Avenue

- Sizeable Spaces, coworking in South Baltimore

- Capital Studios, coworking on Central Avenue

- Beehive Baltimore, coworking at ETC Baltimore

- Accelerator effort being driven by Mike Brenner

- Accelerator/cyber/techspace in Harbor East, led by Karl Gumtow

- Innovation Alliance effort being led by Newt Fowler

- Theater/workspace being discussed by Chris Ashworth/Figure 53

- Shared warehouse workspace being discussed by Andy Mangold/Friends of the Web

- Baltimore Angels (Cangialosi et al)

- Invest Maryland fund (DBED)

- TEDCO’s Innovation fund

- Abell Foundation fund (tied to Accelerate Baltimore)

- Wasabi Ventures fund (investing in city, affiliated with Loyola)

- Fabrication Lab at Towson University

- Fabrication Lab at CCBC

- Fab-lab ideas discussed by John Cutonilli

- Highlandtown workspace development led by Ben Walsh

- Mike Galiazzo, pushing Local-Made, (head, Regional Manufacturing Institute)

Did you know about all of these things? Amazingly, many of the people leading these efforts don’t. Or if they do, they’ve not actually talked to the people involved. To me, this is a problem.

Why? Because folks attempting to gather support for these efforts don’t have all the facts. They either haven’t sat down and listened to people’s motivations, and they’re flying blind. Or it means that they have been unable to sell other like-minded entrepreneurs on their vision, which probably means their vision is not that compelling. And that’s even worse.

But this is not all that’s wrong.

Two Serious Problems

One: there’s a tremendous amount of duplication of effort represented in the list above. Why duplicate all of that administrative, accounting, legal, and governance overhead? By pooling more of these efforts together, that overhead can be minimized and shared.

Two: we don’t have enough human capital to support all of these different efforts. We simply DON’T. Many seem to think it will somehow materialize, but from where I sit, with possibly the widest-angle view of the landscape here of anyone, I don’t see that flow of new startups or even new individuals that can support all of this. It just doesn’t exist.

The Opportunity

Baltimore has an opportunity to become a regional and even international destination for people looking to start or join entrepreneurial enterprises. But for that to happen, we need to have stuff here that can actually become a destination.

And unfortunately, the efforts currently underway are not likely to become that destination because duplicated overhead will keep each effort small and parochial.

However, if more of these efforts pooled their resources and talent – and most importantly identified a BIGGER and more IMPORTANT vision for what it is they are trying to achieve, there would be many positive effects, such as ample governmental and foundation support. And that would be hugely helpful in funneling in the sorely lacking regional and international *human capital* that we so desperately need here!

One Possible Vision

Baltimore has an opportunity to become the hub for digital manufacturing and mass-customization technology on the east coast.

Cangialosi and Lane are already talking about supporting some basic fabrication capabilities at their proposed facility on Key Highway. Gumtow’s effort has placed fab-lab capabilities high on its priorities list. CCBC and Towson have fab-labs, though it’s my understanding they may be underutilized. If you’re going to spend money on fabrication equipment at all, it should be utilized 24×7 in order to maximize the asset.

Something bigger – like taking over the WalMart in Port Covington, or the Meyer Seed Warehouse in Harbor East – could support an accelerator, fab lab, and shared workspace. Thinking a little bit bigger would also have the effect of lowering per-square-foot costs dramatically, and even dramatically altering the real-estate ownership structure.

Baltimore is already home to Under Armour, and at some point in the near future (similar to what happened with Ad.com) it will start throwing off new entrepreneurs with experience in consumer products and manufacturing. Where will they go? Will we keep them here in Baltimore?

Focusing on the intersection of manufacturing and technology is important because it represents the one shot we have at rebuilding even a little bit of a middle class here in Baltimore. Because of that, you’ll find abundant support for such efforts — support that can further reinforce Baltimore’s reputation as an international destination for digital and manufacturing.

The More the Merrier?

I am a fan of placing many, diverse bets rather than making a few large ones. But it’s also important to make strong bets. Unfortunately, Baltimore is right now setting itself up to have many weak positions instead of a smaller number of stronger ones.

I strongly urge the folks leading these efforts to get to know each other and coalesce around a bigger unifying vision that can turn Baltimore into an important regional and international destination for entrepreneurs.

Because without agreeing on a bigger vision, it’s likely that these efforts – each led by well-meaning individuals but with individual motivations – won’t ultimately amount to much, and it would be a shame to waste so much time, effort, and talent.

Thanks to Brian LeGette for his collaboration on some of the ideas underlying this post. Also, everyone on this list is a friend: happy to make introductions and advance the conversation.

December 14th, 2011 — baltimore, business, design, economics

It can be difficult to see the forest for the trees when it comes to defining what it is we in the so-called “tech community” are trying to achieve.

The confusion begins with names: some call it the “startup community,” the “tech business community,” or #BmoreTech. Whatever. I’ve been splitting these hairs for several years now, and with the help of many others and after many personal experiences with organizing groups, events, venues, and businesses have developed a simple but powerful vision for the community.

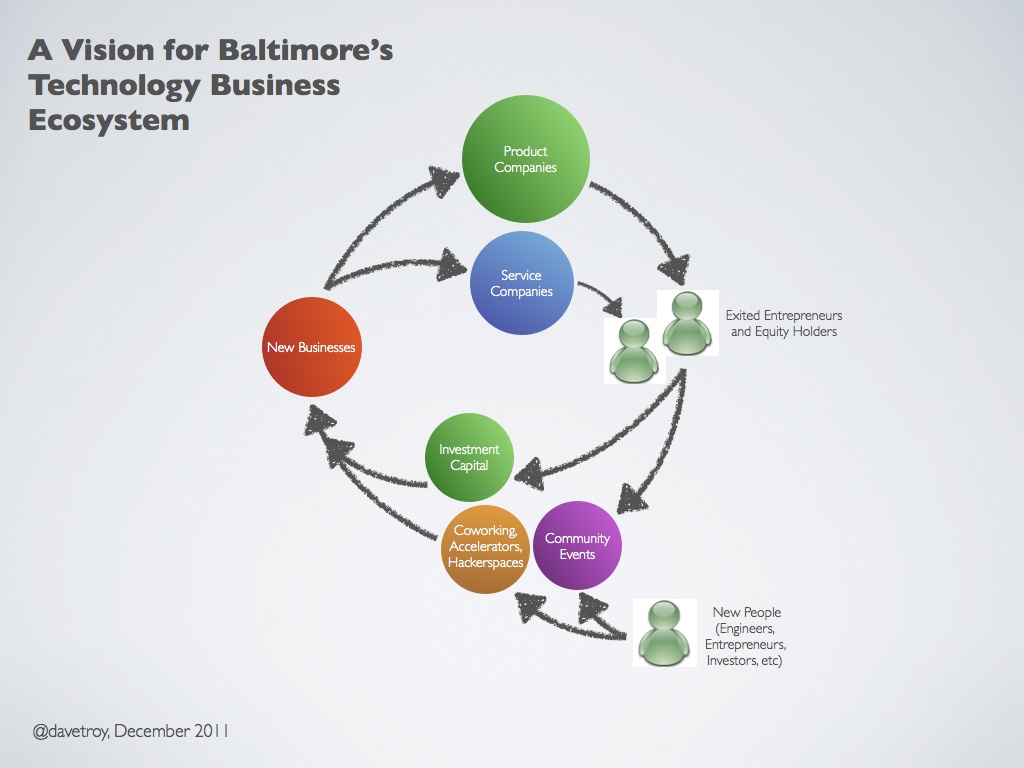

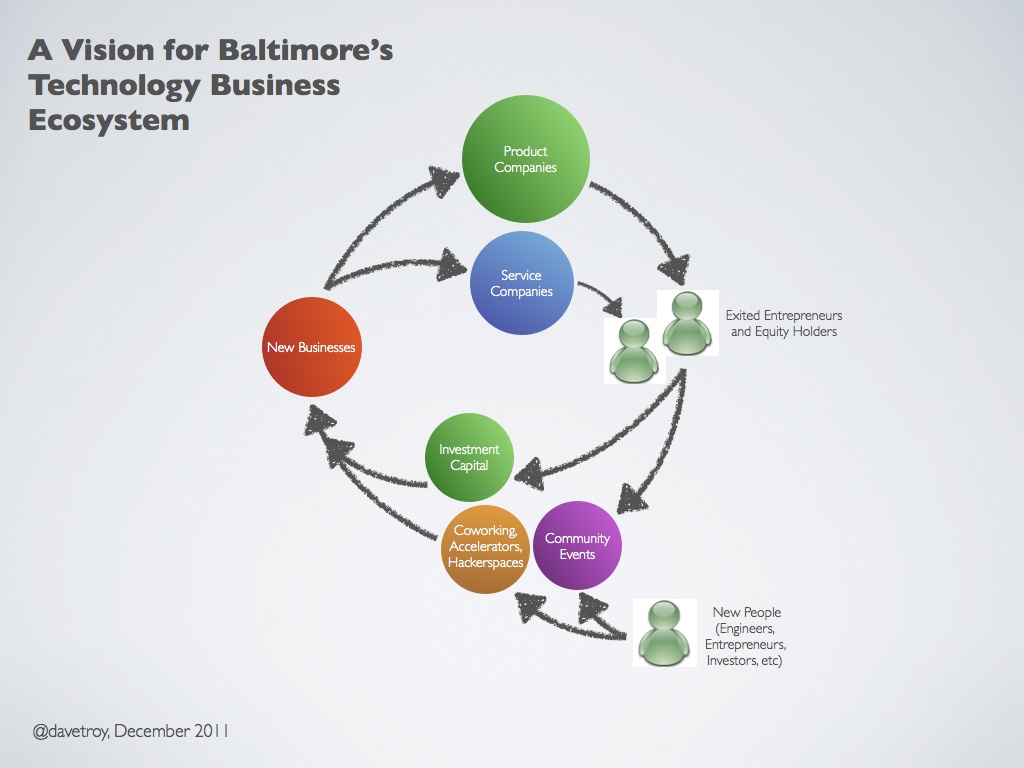

We’re all trying to build an ecosystem that looks something like this (click to enlarge):

Before we get into the specifics of this vision, here are a few basic values that underly it:

- People are the lifeblood of the community. The ecosystem requires educated, creative people. We should strive to enrich and build compelling opportunities for the people in our community.

- Businesses generate the wealth that powers our community. Strong businesses make a strong community. We should aim to make our businesses stronger and more valuable.

- There is a role for everyone. Diversity of expertise and background is essential to a strong business community. We should aspire to have a healthy mix of product companies, service companies, business service providers, and many types of venues and events for relationship building.

- We should celebrate our successes. Celebrating successes, whether they are successful exits or just milestones, is essential to creating a community that values growth, curiosity, and experimentation.

- We should connect people together. Trust and strong relationships are a precursor to new business formation. With strong trust relationships, we’ll have more new businesses and they will be more successful.

With this in mind, here’s how this model works, step by step. It’s a cycle, and for simplicity, we’ll start at the bottom.

- Getting into the mix. (6 o’clock) New participants, exited entrepreneurs, investors, hackers, new entrepreneurs come together via a mix of venues and events. By “venues” I am talking about spaces that offer opportunities for daily, ongoing interaction between individuals. They’re “high touch” while being “low risk.” Think coworking, hackerspaces, regular café coworking, incubators and accelerators, and educational institutions. By “events” I’m talking about one-off or periodic events that afford people an opportunity to get together, get to know one another, and try new things. (Think Bmore On Rails, Startup Weekend, EduHackDay, CreateBaltimore, etc.) New investors can participate in angel groups and pitch events.

- New business formation, access to capital. (9 o’clock) With trust, exposure, and experience, new businesses can form. With the prolonged exposure made possible by the “mix” phase, entrepreneurs can make more informed decisions about who to go into business with and have likely had more time to refine their ideas before ever beginning. This means a lower failure rate for new startups than in a less-developed ecosystem. As for investment capital, some will come from exited entrepreneurs, some from venture capitalists, seed funds, and governmental initiatives like TEDCO and InvestMaryland. We should aim to connect investors with nascent businesses. This will happen naturally to some extent in the “mix” phase, but we should consciously encourage it; bootstrapping should also be an option.

- Business growth. (12 o’clock) Some companies will grow to become strong product companies, others will become service companies. Some people want to grow their businesses to sell them, while others just want to build and run a great business. These approaches are all valid. We should celebrate the formation and growth of all of the companies in our ecosystem.

- Entrepreneur exits. (3 o’clock) Some entrepreneurs will seek the opportunity to exit their businesses and capitalize on their growth. This is most lucrative with product companies. When these exits occur, we should celebrate them as successes of the community as a whole.

- Entrepreneur returns to the mix. (6 o’clock) Exited entrepreneurs should be encouraged to re-engage with the community, either as investors or as active entrepreneurs to form new relationships and new businesses. The cycle starts anew.

That’s really it. If we can make this cycle work, we’ll have a thriving entrepreneurial ecosystem in Baltimore. (This is the exact same cycle that made Silicon Valley great, and is now working in places like Boston, Austin, and New York.)

That’s Great, But Where Do We Stand Now?

We have much of what we need in place: venues, events, investors, and businesses. But the two things we have most lacked are a cohesive vision for how this cycle is supposed to work, and also the last link in the cycle – systematically re-engaging entrepreneurs into the ecosystem.

However, just today came the news that Greg Cangialosi and Sean Lane are forming a startup accelerator in Federal Hill. That’s an example of two successful entrepreneurs getting back into the mix and re-engaging. We need more of that. But we need to make it easier and more attractive for entrepreneurs – there need to be obvious on-ramps and channels. We’re starting to get that in place.

My hope is that this vision, which I have shared in one-on-one conversations with many friends and leaders to much enthusiastic agreement, can now take root as the underlying force that animates our community.

Role of the Greater Baltimore Technology Council

There’s been much discussion about what the role of the Greater Baltimore Technology Council should be, and I submit that this vision, as I’ve articulated it here, is what the group has been moving toward for the last three years – and with Jason Hardebeck (who is himself an exited entrepreneur) at the helm, I believe we can move towards it more quickly now.

The GBTC’s job is to:

- Help build and protect the ecosystem. GBTC should be a watchdog that ensures the ecosystem has the right pieces in place and that they have what they need to function properly. This means working with government, educational institutions, and others to ensure that the conditions required for the ecosystem to thrive are present.

- Accelerate the cycle. The faster this ecosystem operates, the more successful we will be. Specifically, GBTC should connect people together, and celebrate our collective achievements, and help pull our educational institutions into the ecosystem. Ultimately this will pull in more smart, creative people, accelerating the cycle further.

- Make our businesses stronger. By connecting our community together better and providing venues, events, connections, and celebrating our success stories, GBTC can help to make each of our businesses stronger and more robust. This also means connecting businesses to service providers (HR, insurance, accounting, legal) and mentors who can provide value.

For all the drama and hand-wringing, it really is this simple!

Some have wondered whether they “belong” in the GBTC. That’s something every person and entrepreneur has to decide for themselves; there are obviously many valid and valuable ways to participate in this overall vision that are outside of the scope of the GBTC. However, if you care about growing and protecting this ecosystem, and if the group can help your business grow and succeed, I’d encourage you to lend GBTC your support; it just makes good business sense, as GBTC is the only group that has been tasked with this important work.

I know that others in positions of leadership in Baltimore’s tech business community (and at GBTC) share this vision. I encourage your comments and feedback, but before reacting, you might take some time to really think this over. This is something I’ve been looking at for several years, and based on everything I know, this is the right way forward.

The Rest of the Story

Oh, and there’s one more thing.

We all want to prime this pump and get this vision more fully underway, but I also think it’s reasonable to ask how Baltimore’s tech ecosystem fits into the bigger scheme of things. What relationship should we have with other ecosystems, in our region and around the world? Is the point to win or are we trying to thrive? I’ll be touching on this topic in an upcoming post, and it should help to clarify how this vision makes even more sense for Baltimore.

September 14th, 2011 — baltimore, economics, politics, trends

For the many of us who are anxious to move beyond the broken status quo in Baltimore, yesterday’s primary election was disappointing and frustrating.

Still, there’s a lot of valuable information to be gleaned that helps us build a better map of Baltimore’s electorate – from its many problems to its deep divisions.

- Turnout was pathetically low: 70,416 of 380,000 (18.5%). Some have said that “the issues didn’t resonate with voters,” and that could be true. However, a bigger trend to watch for is the decline of turnout generally. Many “seniors,” who made up the core of the voting population, are now dead or dying. How will we address this trend?

- Voters are either displeased with, or not sure about, Rawlings-Blake’s leadership. 48% of voters felt we are definitely on the wrong track with Stephanie Rawlings-Blake. Many more aren’t sure, but wanted to give her a chance with a full term in office. And there are 310,000 other voters who must feel so disconnected that they declined to express any opinion at all. There is no mandate here.

- Otis Rolley swept the online progressive community. Any observer of the online world would have told you that Otis would have won in a landslide; his supporters kept a steady drumbeat on Twitter, Facebook, and on blogs throughout the campaign, and especially election day. But however strong he may have been in that community, he garnered just shy of 9,000 votes. No other candidate received any measurable online presence. This is further proof of Baltimore’s deep digital divide.

- Too many candidates spoil the race. This would have been a very different race if Rolley, Pugh, Landers and Conaway had teamed up to challenge the Mayor. Pugh had nothing to lose by running; she keeps her Senate seat. Landers could have assisted Rolley with his tax plan. Conaway had no business being in the race at all. A two-way race between a Pugh-endorsed Rolley and Rawlings-Blake would have had a very different donor make-up, would have told a different story in the press, and would have had a different outcome.

- Name recognition still carries weight. Dithering City Councilman Carl Stokes won again in the 12th district, despite a strong and credible challenge from the earnest and organized Odette Ramos. “Pistol Pete” Welch held his (inherited) seat, despite challenges from Abigail Breiseth and Christopher Taylor. These were both split-field races against “name brand” incumbents that also demonstrated the persistent racial divides in Baltimore.

- Foolishness and incompetence will eventually get you booted. In a bright spot, it was nothing short of refreshing to see that Belinda Conaway was ousted from her seat by newcomer Nick Mosby. Conaway, in suing blogger Adam Meister for $21M (for his factual articles about her place of residence), spurred Mosby to run, and he won – 2,747 to 2099. One bear down, two to go.

- City Council is broken. Baltimore’s system of government has a strong executive (Mayor) and a weak legislature (City Council). The City Council has been such a refuge of scoundrels that few want to be associated with it. Some suggested that Landers or Rolley should run for City Council president as a way to some day be mayor. Frankly, I wouldn’t trust a Mayoral candidate that was coming from City Council. There’s too much incompetence and corruption.

- Our elections are broken. It’s ridiculous that our choice of Mayor would be made in a September primary, but with no viable Republican or Independent candidates, it’s the way things are. We need to get open primaries, or hold a run-off in November. My understanding is that this can be changed via petition and referendum, which means it is doable outside of the current political structure. This needs to be pursued immediately. Too many voters were disenfranchised in this process, and it’s unreasonable to ask people to switch parties in order to vote.

- The Mayor spent (wasted?) roughly $2 Million on just 37,000 votes. In an election with just 71,000 votes cast, nearly $4 Million was spent. In a real way, the Mayor (and her tax-break seeking contributors) bought the election. The cost in the end to her was roughly $54 per vote. In a city with so much pain and brokenness, I find this morally repugnant. It’s worth nothing that Otis Rolley also spent roughly $50 per vote, so this metric is not a coincidence. It’s the “acquisition cost” of a vote in a top-tier modern Baltimore City election. We need to focus on lowering that cost.

- The incumbent Mayor always wins. This is because the incumbent Mayor influences city business, and city contractors and developers know Baltimore is a “pay to play” town. They pay, they get favors. This allows the incumbent to buy votes – for $54 each.

- Kiefaber was the favorite protest vote. Tom Kiefaber, the embattled former owner of the Senator Theater, who has been raising red flags about Baltimore Development Corporation (and interrupting City Council meetings) was the runner-up protest vote in the contest for City Council president with 5,390 votes. While Jack Young won in a landslide, the fact that a candidate like Kiefaber could get any traction at all shows just how deeply folks distrust – and ridicule – that body and its leadership.

- The Sun missed a chance to create a better horse race. Jody Landers was right to complain that only 2 of the 5 members of the Sun Editorial board live in the city; there is also only one African American. If the Sun is going to pretend to have opinions relevant to city residents, those ideas should come from people that will have to live with the consequences. The editorial bent of the Sun’s coverage did not develop any kind of horse race between candidates, and frankly seemed to be pushing for the incumbent all along. In my opinion this was not just bad for Baltimore, but bad for business for the Sun. How many more papers could they have sold by developing a more compelling narrative?

Those of you that know me know that my support for Otis Rolley was born out of a belief that Baltimore is worth fighting for, and that Baltimore deserves better. I share that belief with Otis, and with Tom Loveland, Aaron Meisner, Brian LeGette, Terry Meyerhoff Rubenstein, and so many others who supported his campaign. I supported Otis because of my beliefs; my beliefs are not shaped because of my support of Otis.

This is an important distinction. Too often when folks think “politics” they think it’s about pitting candidates against each other, and insider interests and gaining financial advantage. But in this case, that has nothing to do with it. I simply believe that we are on the wrong track and that we can do better. I have nothing to gain in my support of Otis – unless you count living in a city that might have a shot at being strong again, and one where its leaders listen to citizens.

But we also learned something else. It’s tempting to think that real change can occur through online organizing and Twitter and Facebook and the coming-alive of the “new” Baltimore or the youth vote, or via SMS messages or what have you. And sure, those things will play a part in any election going forward.

But the most important lesson is that Baltimore is a city of tribes: poor, rich, black, white, Hispanic, digital, homeless, addicted, corrupt, idealistic, and blue-collar – to name only a few. Few of us ever break out of our own tribe. We surround ourselves with our own points-of-view and hear what we want to hear.

For Baltimore to grow, we need to break free of our tribes. We need to be occasionally uncomfortable. We need to do real public service, and build up the kind of roots in our community that ultimately allow meaningful change to occur.

As Otis said last night, this is just the beginning of a campaign to take back our city and stand up for Baltimore’s future. But that won’t be easy. Done right, it will make us uncomfortable, as we reach out across tribes. It will take serious commitment, and much more than “Likes” on Facebook.

In the end, it will require our full and unconditional love – of our fellow citizens, and our city.