Entries Tagged 'economics' ↓

February 8th, 2009 — baltimore, business, design, economics, philosophy, programming, social media, socialdevcamp, software, trends

Twice last year, I had the experience of putting together SocialDevCamp East, a barcamp-style unconference for software developers and entrepreneurs focused on social media.

Sounds straightforward enough, but that sentence alone is jam-packed with important design decisions. And those design decisions carried through the entire event, and even into its long-term impact on our community and our community’s brand. I’ll explain.

Barcamp-Style Unconference

In the last few years, the Barcamp unconference format, focused on community involvement, openness, and attendee participation has gained a lot of traction. I won’t write a ton here describing the format and how it all works as that’s been done elsewhere, but the key point is that this is an open event which is supported by and developed by the community itself. As a result, it is by definition designed to serve that community.

So what are some other design implications of choosing the Barcamp format? Here are two big ones.

First, anyone who doesn’t think this format sounds like a good idea (but how will it all work? what, no rubber chicken lunch? where’s the corporate swag?) will stay away. Perfect. Barcamp is not a format that works for everybody – particularly people with naked corporate agendas. It naturally repels people who might otherwise detract from the event.

Second, the user-generated conference agenda (formed in the event’s first hour by all participants voting on what sessions will be held) insures that the day will serve the participants who are actually there, and not some imagined corporate-sales-driven agenda that was dreamed up by a top-down conference planning apparatchik three months in advance.

The fact that there are no official “speakers” and only participants who are willing and able to share what they know means that sessions are multi-voiced conversations and not boring one-to-many spews from egomaniacal “speakers.”

The Name: SocialDevCamp East

We could have put on a standard BarCamp, but that wasn’t really what we wanted to pursue; as an entrepreneur and software developer focused on the social media space, I (and event co-chairs Ann Bernard and Keith Casey, who helped with SDCE1) wanted to try to identify other people like us on the east coast.

We chose the word Social to reflect the fact that we are interested in reaching people who have an interest in Social media. It also sounds “social” and collaborative, themes which harmonize with the overall event.

We chose the wordlet Dev to indicate that we are interested in development topics (borrowing from other such events like iPhoneDevCamp and DevCamp, coined by Chris Messina). This should serve to repel folks that are just interested in Podcasting or in simply meeting people; both fine things, but not what we were choosing to focus on.

Obviously Camp indicates we are borrowing the Barcamp unconference format, so people know to expect a community-built, user-driven event that will take form the morning of the event itself.

We chose East to indicate that a) we wanted to draw from the entire east coast corridor (DC to Boston, primarily), and b) we wanted to encourage others in other places to have SocialDevCamps too. Not long after SDCE1, there was a SocialDevCamp Chicago.

Additionally, our tagline coined by Keith Casey, “Charting the Next Course” indicates that we are interested in talking about what’s coming next, not just in what’s happening now. This served to attract forward-looking folks and set the tone for the event.

The Location

We wanted to make the event easily accessible to people all along the east coast. Being based in Baltimore, we were able to leverage its central location between DC and Philadelphia. Our venue at the University of Baltimore is located just two blocks away from the Amtrak train station, which meant that the event was only 3 hours away for people in New York City. As a result had a significant contingent of folks from DC, Baltimore, Wilmington, Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, many of whom came by train.

Long Term Brand Impact

These two events, held in May and November 2008, are still reverberating throughout the region’s community. At Ignite Baltimore on Thursday, SocialDevCamp was mentioned by multiple speakers as an example of the kind of bottom-up grassroots efforts which are now starting to flourish here.

The event has the reputation of having been a substantive, forward-looking gathering of entrepreneurs, technologists, and artists, and that has gone on to color how we in the region and those in other regions perceive our area. Even if it’s only in a small way, SocialDevCamp helped set the tone for discourse in our region.

Design? Or Just Event Planning?

Some might say that what I’ve described is nothing more than conference planning 101, but here’s why it’s different: first, what I’ve described here are simply the input parameters for the event. Writing about conference planning would typically focus on the logistical details: insurance, parking, catering, badges, registration fees, etc. Those are the left-brained artifacts of the right-brained discipline of conference design.

Everything about the event was designed to produce particular behaviors at the event, and even after the event. While I make no claim that we got every detail perfect (who does?), the design was carried out as planned and had the intended results. And of course, we learned valuable lessons that we will use to help shape the design of future events. Event planners should spend some time meditating about the difference between design and planning; planning is what you do in service of the design. Design is what shapes the user-experience, sets the tone, and determines the long-term value of an event.

More to Come

I’ve got at least 3 more installations in this series. Stay tuned, and I’d love to hear your feedback about design and how it influences our daily experience.

WARNING – GEEK/PHILOSOPHER CONTENT: It occurs to me that the universe is a kind of finite-state automaton, and as such is a kind of deterministic computing machine. (No, I was not the first to think of this.) But if it is a kind of computer, then design is a kind of program we feed in to that machine. What kind of program is it? Well, it’s likely not a Basic or Fortran program. It’s some kind of tiny recursive, fractal-like algorithm, where the depth of iteration determines the manifestations we see in the real world.

As designers, all we’re really doing is getting good at mastering this fractal algorithm and measuring its effects on reality.

See you in the next article!

February 5th, 2009 — baltimore, business, design, economics, philosophy, social media, software

The First Church of American Business teaches that virtue accrues from execution, and that the ability to manage big, complex to-do lists either personally or via delegation is the key to getting ahead in business.

From there it also holds that competition is all about having and managing longer and more complex to-do lists, and beating out the other guy who’s presumably doing the same thing. Books with titles like “Execution,” “Getting Things Done,” and the “7 Habits of Highly Effective People” depict the business world as a crazy-making self-perpetuating scheme of testosterone-fueled competition, which ultimately aims to canonize its Saints the way the sports world does its highest trophy winners.

Business book writers have it particularly easy; they go back and look for the “winners” of this apparent competition (Jack Welch, Bill Gates, Eric Schmidt) and assign them all manner of superhuman qualities. Occasionally they come across somebody who somehow managed to get on top without shaming (and presumably out-executing) all of his or her peers, and they shrug in disbelief and assume that they must have “the vision thing” and canonize the schmuck anyway; the last thing the high priests of productivity would want to admit was that they didn’t see someone coming.

My deepest wish is to go back to 1960 or 1985 (maybe both) and gouge out the eyes of these practitioners with their own tassel loafers. We’ve seen how this all worked out; this approach to business has led us to the only place it could: a testosterone-fueled sham of an economy.

Certainly execution is important. But in the rush to assign virtue to execution itself, we’ve lost sight of what it is we’re executing – that “vision thing.”

Design is the most important force for good in the world today. Overstated? I don’t think so. Design indicates intent. I believe humanity has good intentions for the world; therefore I believe that design is the way in which we will manifest those good intentions.

Many people are confused about what design is. They confuse it with industrial design (iPod, Beetle, Aeron Chairs) or graphic design (packaging, advertising, marketing, websites), or simply assume it’s one of those “art things” that they don’t have to worry about because they didn’t study it in business school.

But in fact, people design things every day. We are all designers of our lives. In the simplest choices, we are signaling our intentions about how we want to interact with the world and sending subtle cues about the kinds of interactions we desire.

Getting good at design is a little bit like becoming a Jedi master – it comes from a place inside where less is more and where silence is more powerful than sound. It’s about looking for the reasons why something will work rather than the ways it might fail. It’s about finding the line, the melody, the art, the poetry in mundane transactional details and teasing it out to make it serve you. It’s tough to explain, but over the next few days, I’ll be reviewing some recent, unconventional examples of design in my own experience.

Design is all about executing a small number of the right tasks.

January 16th, 2009 — art, design, economics, geography, philosophy

A few weeks ago, my wife picked up a book called The Written Suburb at a Greenwich Village used bookshop about Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and how it was an invented, postmodern place, designed to become a mythological homeland of the American realist movement.

As the area was home to painters like Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, and Andrew Wyeth, its history was certainly intertwined with that of American art. The Brandywine River Museum has done a fine job selling itself as the First Church of Delaware Valley Realism and enhancing the myth of Brandywine River as a seat of not just Realism but also of the Real.

As a teenager, I had visited the Brandywine River Museum, and when pressed to write a paper for an art class, I chose to write about the work of Maxfield Parrish, the prolific American illustrator whose work is featured there. I was enchanted by his technical method, which employed multilayer transparencies and unusual materials, but my teacher disputed that his stuff was really “art” and undoubtedly had wished I’d chosen to write about Picasso or Millet — somebody “real.”

With the news of the death of Andrew Wyeth, the whole question of whether the Brandywine River school really produced “art” is back in the news again. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York refused to show his “Helga” paintings on the grounds that they were not, or at least weren’t very good.

The Museum of Modern Art keeps Andrew Wyeth’s most famous work Christina’s World (1949) in a back corner, and it’s always fun to watch people discover its presence. They stumble upon it, and are surprised at how it moves them. As an icon, they are completely ready for it to be trite and clichéd, but in person it still seems to catch people up.

Art purists would say that the only valid art is work that’s done for art’s sake alone: without guile, without intention to build an audience, without regard to populism. Arguably, only art that fits this definition can advance what’s been done before it in the same vein: populism and intellectual progress usually don’t mix.

However, another definition of art is any work that conveys emotion, and on this score, the Wyeths and the Brandywine River School perform well enough to merit attention. That 200 million people can name Wyeth as one of their favorite artists shows his communication has been effective, however invented or populist it may be.

The intersection between art, populism, and commerce is an interesting place to poke around. Here are the seams of our culture, where values, money, and progress bang up against each other.

The Brandywine River Museum touts the artistic authenticity of an invented place, and the Wyeths, Pyle, and Parrish are all promoted as invented artists, designed to insure the flow of tourist dollars into Chadds Ford and Kennett Square — beautiful places, to be sure, and if you squint you can convince yourself the place conveys the feelings the art is trying to make you feel — especially at this time of year, when the browns, greys, white and cold look and feel just like a Wyeth landscape.

But in the end, that’s a leap of faith on the part of the viewer. Sometimes art requires the viewer to become complicit in its own invention.

January 2nd, 2009 — business, design, economics, trends

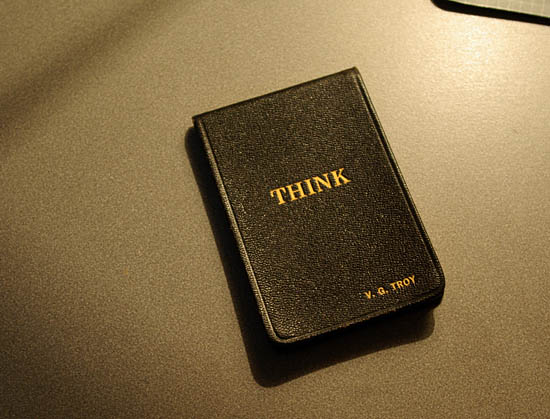

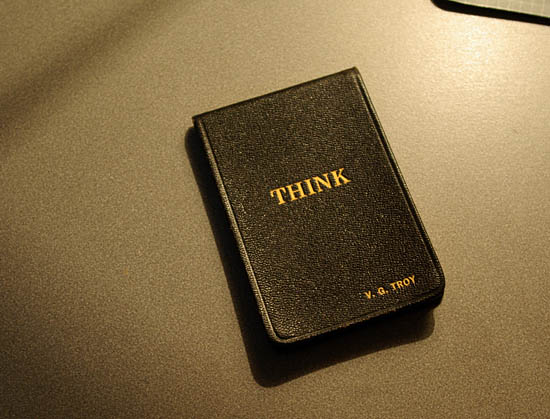

Yesterday at my parents’ house I stumbled across a small black 3″ x 4″ leather-covered notepad with the word “THINK” on it in gold, and my grandfather’s initials (V. G. TROY) embossed in gold in the lower right corner.

This was an original IBM Think Pad.

Thomas Watson, founder of IBM, famously instructed his employees to “THINK” and had emblazoned the word all over the company’s offices; each employee carried a “THINK” notepad. And it seems they gave out various similarly-themed promotional material: my grandfather was a prospective customer to IBM, as he managed the automation of the New York State Insurance Fund in the early 1960’s. My wife recalls that her great-grandfather, an accountant, had a large “THINK” sign over his desk, presumably encouraging his supplicants to refine their queries.

I got to considering what it says about a company (arguably a society’s largest and most successful company) that is so fanatical about a single word like THINK. And what does it say about a company (and a society) that abandons that slogan?

THINK, in all caps and repeated like a mantra, says a lot. It implies that as individuals we are capable of logical contemplation that will result in conclusions that are universally true; that there is in fact one truth that all of us can visualize if we simply utilize our intellect and the tools of logic. What a view of the world (and of business) this is: there is only truth, there is only competitive advantage, there is only logic. If you want to succeed, all you have to do is find the truth.

Somewhere in the last 40 years, American business became unglued from truth.

Success in business became a kind of alternate-reality game, with a billion realities competing against one another, and perception trumping reality. No wonder a word like THINK seems obsolete and quaint now: it ignores the reality of Wall Street and all the complexity that comes when you’re painting a different picture for customers, employees, and shareholders.

If we were to choose a word that sums up the current business ethos, it might be something like “POSTURE” or “PROFIT”. But it’s surely not THINK; thinking has been out of fashion for some time, and it may just be that as we dismantle this fake, Bernie Madoff economy, we discover that if we want to achieve real economic success again we could do worse than to adopt Mr. Watson’s old mantra.

THINK.