Entries Tagged 'economics' ↓

October 24th, 2009 — business, design, economics, social media, software, trends

Technology investment bubbles have given many entrepreneurs the impression that success in tech is all about coming up with a “cool idea,” pitching it to a VC, getting funding, building up the business, and then exiting in high style.

First, this is a fairy tale, second, this will not happen to you, and third, what you’re observing is the product of a highly evolved network of peers, of which you are likely not a part.

What Happens in Palo Alto Stays in Palo Alto

What you see taking place in Silicon Valley is the result not of people betting on “cool ideas,” but of people betting on teams and connections. Before every VC deal, there is an exit strategy in mind. Every VC-backed valley startup is an outsourced R&D play.

Ever notice that many large tech firms grow primarily by acquisition? Most have comparatively lean R&D operations; this keeps experimenting off of their balance sheet, thus improving profits and lifting stock prices. Those stock prices are what give them the fuel to make good sized acquisitions, which in turn is the incentive for startups to grow and for VC’s to fund them.

This is the capitalist cycle in its most fully evolved form. Sometimes those acquisitions work out, sometimes they don’t, but the process feeds the machine and it becomes self-perpetuating. This process is literally the grist for the innovation mill that is Silicon Valley.

Why You Should Forget About VC’s — For Now

If you’re not already plugged into this world (meaning you have a lot of contacts there and have a specific idea of a strategy to get funding and an exit before you start), you probably have no place talking about VC’s at all. So ban it from your vocabulary. They’re not interested in you and won’t be. Yet.

Instead, think about how you’re going to build value outside of that network. It is totally possible, but don’t get distracted thinking about VC’s when you should be thinking about bootstrapping and investment from friends, family, and angels.

The good news? Most software startups can be launched for $50K or less these days. Build the minimum viable product, ship it, and then follow lean startup methodologies to iterate towards something that is valuable to the market. Once you have done that, established a revenue stream and can demonstrate some reason why venture capital investment will help you grow fast and capture a market position that you couldn’t capture otherwise, you may be ready to talk to a venture capitalist.

But more likely, investors will come to talk to you! If your startup shows real promise, VC’s will likely seek you out. If you work with some angel investors, they will likely have networks that can help you secure a next round of investment. It will happen naturally. Stop thinking about VC’s. They will find you. Worry instead about building value.

Think Investors, Not VC’s

Yesterday I wrote a post that suggested that entrepreneurs should always think like investors, and always consider what an investor would think of the company. I stand by this, but I am absolutely not talking about VC’s in the early stage. You are not ready for VC’s in the early stage, especially if you are not “plugged in” to the valley culture.

So, think like an investor. Your investors are: you, your family, angels, and possibly local government business development funds. Forget about VC’s for now. If you build value for your yourself, your customers, and your first round of investors, VC’s will come knocking if they think they can help.

October 23rd, 2009 — business, design, economics, software, trends

Entrepreneurs sometimes think that they are the ones “doing the work,” and that investors are but a necessary evil: parasites looking for a free ride on the back of the hardworking startup.

This false dichotomy blinds entrepreneurs to the reality that they, too, are investors and must always think like one. It deeply affects your decision-making process.

The Business Case

Why is your entrepreneurial endeavor a good idea? In a capitalist system, all entrepreneurial activity has just one purpose: to make money. Presumably, your business idea will require the investment of some of both your time and your money. Your time has opportunity cost associated with it (what you could be earning doing something else); and your money could be in the markets earning 5-7%. Over time, your business idea should return a value greater than 7-10% compounded in order to make it worth doing at all. Many businesses can yield several hundred percent returns, either in the form of free cash flow or an exit (selling that cash flow) later on.

You might argue 1) there are other reasons besides making money to start a business, 2) capitalism has flaws, 3) we don’t actually live in a capitalist system. These are fascinating, valid arguments, but let’s put them aside for now.

If you accept the idea that making money is the only reason to start a business, then why would you spend your time and invest your money in a business concept that you would not ask someone else to invest in as well?

Bad answer: Because you don’t think an investor will “get it” and you don’t want to waste your time figuring out how to convince people you don’t know that your idea and team are worthy of their cash.

Good answer: Because you don’t need additional cash and don’t want to give up equity right now. You might consider taking investment after your prototype is complete to make a couple of key hires.

This “bad answer” is a kind of exceptionalism: you think that you are special, that you have all the answers you need, that this time it will be different, and that you won’t ever need investors. But like most exceptionalist attitudes, this mindset is a self-deception.

Always Be Transactable

In economics, transactability is the degree to which something can be traded, usually for money. If you don’t think like an investor yourself, you are adopting a mindset of non-transactability early on. You’re essentially saying, “I don’t even want to think about trading equity for money because I am exceptional and I don’t care about what anyone else thinks of my business.”

The problem with adopting a non-transactable mindset is that it tends to persist and self perpetuate. When do you go from being non-transactable to transactable? When do you decide it’s okay to give up equity to key hires or partners? When do you decide it’s okay to accept a small amount of investment? What will I do when it’s time to sell the business?

Many early-stage entrepreneurs dismiss these questions, assuming that they will “figure them out when they get to them,” or they say that they’ll “never sell their business.” These are both flawed arguments: if you don’t think about how you would trade equity for cash (and vice-versa) from the start, you are likely to handle any situation that requires it poorly.

Your Business Has a Valuation From Day One

This morning, Apple has a market cap valuation of $184.64 Billion (more than Google, less than Walmart). Your business is probably worth less, but it still has a value!

The “valuation” of your business is, quite simply, what someone else would be willing to pay to own it. That is usually a combination of the depreciated value of your assets, less your liabilities, plus a multiple of whatever free cash the business might be available after operating expenses. Some businesses get really high exit multiples (product companies, 8-10X net) and others get lower exit multiples (service companies, 3-4X net). There are no “rules” for business valuation; it’s a lot like home prices. You can look at comparables and take some guesses, but it boils down to what a buyer is willing to pay. It’s nice to have a lot of buyers, too.

You should always be thinking about maximizing the value of your business. What would somebody else pay to be in your shoes? In the early stages, the answer is almost “not much” or even negative. That’s to be expected, but over time, if you succeed the answer will start to be $100K, or $1M, or $10M. You need to be thinking about that trade all the time, and at least have some sense of what your business valuation is and how you might maximize it.

Everybody Is an Investor

You may not think so at first, but you are always asking for investment. If you are hiring someone, they are evaluating your business plan, your chances of success and whether your company represents something they want to invest their time in.

Your trading partners are also evaluating you and determining if they want to enter a relationship with you. Your customers also evaluate whether they should bet on doing business with you.

By keeping transactability always in mind and caring what others think of your business, you will be more likely to appear viable to these constituencies. And being transactable helps you make better deals with partners and customers: you learn what can be traded and what can’t.

I’ll Never Sell!

Some people have no intention of ever selling their business, and instead just want to be their own boss and make some money. This is fine, and most people call this approach running a “lifestyle business.” It’s well suited for sole-proprietors and can offer great personal freedom.

But this can be a treadmill: most often, you’re trading money for your time. Even at a high hourly rate, your income is tied to how many hours you can bill. Take a month off and you lose a month’s pay.

Or, you may have built up a clientele that pays recurring subscription fees or other residual income. While this can free up your time somewhat, if those recurring revenues are not high enough to sell to an acquirer, you can still be stuck.

At some point, you will want to get off this treadmill. What then? Do you just shut down the business and throw it away? That’s a very bad idea. Ask again, what would someone else pay to be in your shoes? The answer might be $50K, or $200K, or $1M depending on your business. You can and should capture this and shop it around in the market.

Or, you might have a service company that you want to pass on to your family. What then? What’s that worth? How do you manage your estate planning effectively?

Any business where “you” are the face of the business can be tough to sell in the market. But even these kinds of businesses can be sold. I’ve seen this happen, and it’s usually for meagre amounts of money. (Think computer sales + repair, HR services, accounting.)

Precisely because of their low market valuations, I’m not big on lifestyle companies. But my point is that they too have valuations that someday need to be reckoned, and to start any company – even a lifestyle company – without thinking about business valuation, investors, and transactability is foolish.

Always Have a Pitch

The simple way to keep your head on straight is to always have a pitch. You should always think about how you would explain your business to an investor. It may well be that the only investor you are concerned about pitching early on is yourself, your partner, your friends and family, or even your spouse. But you should also be thinking about what other kinds of investors (angels and yes, even VCs, where and if applicable) might think too. Because you just might need them later.

You are your own lead investor. If you cannot articulate why you’re doing what you’re doing and why it might generate good returns in the long run, then why do it?

October 22nd, 2009 — business, design, economics, software

For a software startup, having a good idea is important, but a good team is essential.

Good ideas are easy to find; I keep a list of interesting business and tech ideas that I constantly update and probably have a couple hundred at the ready.

What’s hard to find, and is much more important for success, is a good team. What are the ingredients of a good team?

Go All In: Look for “Crazy Eyes”

It’s tough to go it alone. While you might succeed nurturing an idea as a side project, your chances of success go up dramatically when you band together with people who complement your skills and are willing to do what it takes to get something to market as quickly as possible.

I call it “crazy eyes.” You need to be able to look somebody else in the eyes and catch that wild-eyed glint of insane dedication – and truly commit to each other as collaborators. If you can’t find people to take risks with, you probably won’t be able to bring your idea to fruition.

Proper Casting

Putting together a good team is all about having the right people in the right roles. First, that means choosing the right people to collaborate with. Second, it means knowing and being honest about the strengths and weaknesses of each individual on your team.

All too often, I have seen people call themselves CEO that really ought to be “Chief Software Architect.” Or people in operational roles who clearly can’t stand being around other people. While it’s tempting to label yourself and your cofounder as COO and CEO, you need to be honest (and educated) about whether you are really right for these positions.

When you go to talk to potential investors, they will sniff out this kind of bad casting right away, and they will just assume you have bad judgment. If they think you have bad judgment about a simple thing like properly casting yourself, then they think you will have bad judgment about everything else; they certainly won’t trust you with investment funds.

Proper casting is a sign of honesty, clarity, and good judgment. It’s key to connecting with investors. Even if you don’t think you need investors, prospective partners and employees pick up on your casting judgment also. Do it right.

A Good Team Always Survives

What may seem like a great idea may turn out to be a bad one, or one that needs to be changed to be successful. Maybe it turns out that kids don’t want to play with horses in your 3D virtual world. Maybe instead, 50 year old men want to play war there. A good team figures that out and capitalizes on it. A bad team spends ever greater sums of money trying to embellish the pretty horses and advertise in kids magazines.

Even in the worst case, a good team that knows its strengths and weaknesses will know how to salvage assets and return value to investors (license the tech to others, etc). A bad team gets mired up in personality conflicts, personal crises, falls apart and becomes toxic to everyone.

This is why investors will almost always bet on a good team with an unproven idea over a sure-fire idea and a so-so team. Good teams deliver returns no matter what.

Good Teams Make Markets

I’ve seen lots of ideas that sound impossible on the surface turned into great businesses through the skills, connections, and experience of their teams. Want to sell WiFi in airports? Sounds impossible, but not if your COO spent 10 years as the director of purchasing for HMS Host. Want to sell an avionics upgrade to the Air Force? Sounds tough, but not if your CEO spent 10 years on contracts at Lockheed.

What a team brings to an idea is more important than the idea. Good ideas are a dime-a-dozen. Finding the people to make a good idea work is incredibly difficult.

Stay Calm and Open to Change

It’s easy for partner relationships to become emotional and strained. Often, partnerships form as a handshake and a promise of 50-50 equity. Operating agreements and buy-sell arrangements often come later, breed resentment, and then become set in stone as people invest increasing amounts of sweat equity.

Don’t let relationships get in the way of execution. While you may be passionate and emotional about your idea, you should be calm and cool about your relationship with your team members. Remember, it’s all about proper casting. Do whatever it takes to put people into the right roles and immediately address any questions regarding equity, hurt feelings, and the like.

There’s no better way to turn a good team bad than to let equity and casting issues fester.

Know a Lot of People

The best way to insure proper casting is to choose the right teammates to begin with. The best way to do that is to know lots of people with diverse skills. This will keep you from going into business with your college roommate and instead partner with people who have the skills that round out your team.

Just Say No

“No” is the most powerful word in business. The pressure to be “moving forward” in our society is intense where to buy propecia. But if team is so important and you also believe in your idea, it doesn’t make sense to move forward with the wrong team or the wrong idea. Just say “no.” Instead, wait it out and find the right team, or at least part of the right team before moving forward. Or change your idea.

Every day I see smart entrepreneurs, under pressure to “move forward,” squandering their time by pursuing an idea with a “halfway there” team. I don’t mean to belittle any entrepreneur’s efforts, and I certainly wouldn’t bet against them. But there’s a difference between doing something just to be doing it (and not really believing in it) and going all-in with people who have what it takes to succeed.

And yes, many entrepreneurs don’t really believe in what they are doing: if they did, they’d quit their day jobs. Building up and then tearing down a half-baked startup takes time as well as real and emotional capital. Why waste all that? Life is short. Find the right teammates (if you need anyone beyond yourself to begin) and then go all in. Your support network will rally around you.

What Investors Look For

You may think investors read your idea first. They don’t. They look at where you live. They look at who your attorney is. They look at your background. They look at your team. Smart investors know that your network says more about you than anything else.

Once they’ve figured out “who you are,” then they consider your idea and determine if you have any hope in hell of delivering what you’re promising. Investors know ideas are cheap; they see them all the time, and usually have many ideas of their own. What they are looking for is why they should bet on you to deliver on your particular idea. And frankly, they are looking to see if you are delusional!

If you are realistic about your chances, have spent time building a good team, and have cast your team members in appropriate roles, most investors will look at any plausible idea favorably. It doesn’t hurt if you share some common acquaintances, either; shared social networks and shared values help ensure long term commitment to the investor and the community. This is why angels almost always invest close to home.

Local Is Best

It’s both tempting and possible to put together a “virtual” company with folks spread around the world. However, investors see this as a sign of team weakness. It means video conferencing instead of face-to-face meetings. It means slower response times. It means travel costs and weaker relationships. In the end, it lowers your chances of success and is just a pain in the ass.

In the context of larger established companies, having some remote workers can make lots of sense. But if you’re trying to launch a startup, do it with the people in your own backyard. Can’t find the right people? Keep digging; see below.

Build Your Network

The single best thing you can do to as an early stage startup is to build up your network of potential team members. And don’t just collect business cards at networking events. Build real relationships. Figure out what makes people tick. Spend time in environments where you take risks with people and try out new things. They will become your casting pool, now and in the future.

One of the best ways to do that is to get involved in your local tech community. Here in Baltimore, we have Beehive Baltimore, which lets freelancers and entrepreneurs spend time working together. From Beehive, TEDxMidAtlantic was born. That event brought over 100 amazing entrepreneurial thinkers together in organizing a 500 person, very complex event. Go to events like Ignite Baltimore; listen to the people around you and think about how you can collaborate with them. Grab lunch and beer with people!

These are just a few observations I have gleaned from my work with Baltimore Angels and with starting and observing many companies over the last 23 years. I welcome your comments!

October 19th, 2009 — business, design, economics, social media, software, trends

I typically hate writing about topical technology subjects, because most often it’s reactive, worthless speculation.

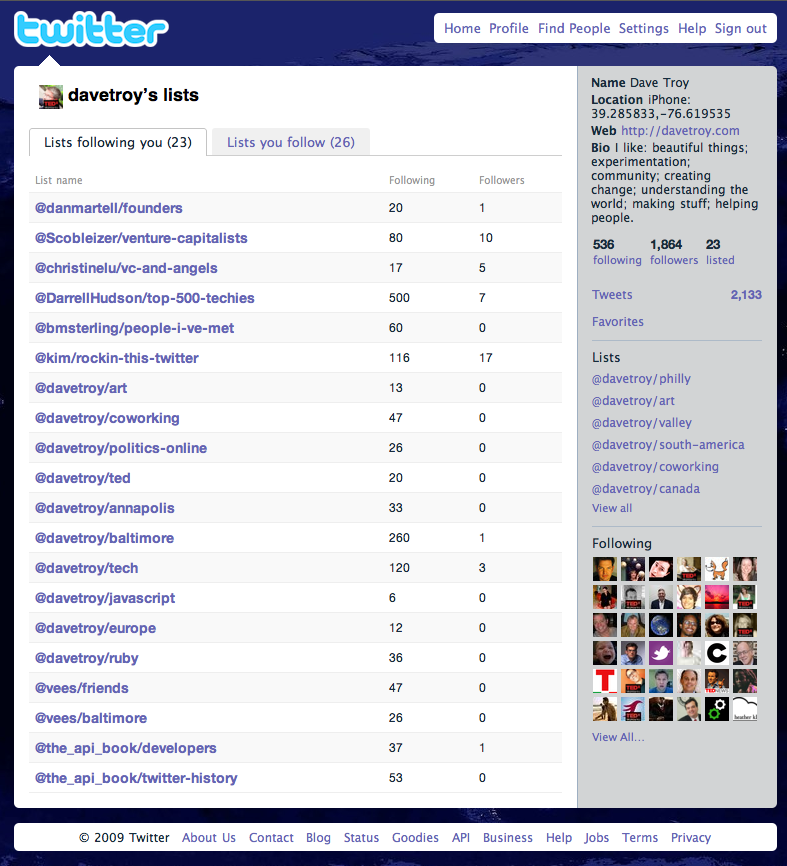

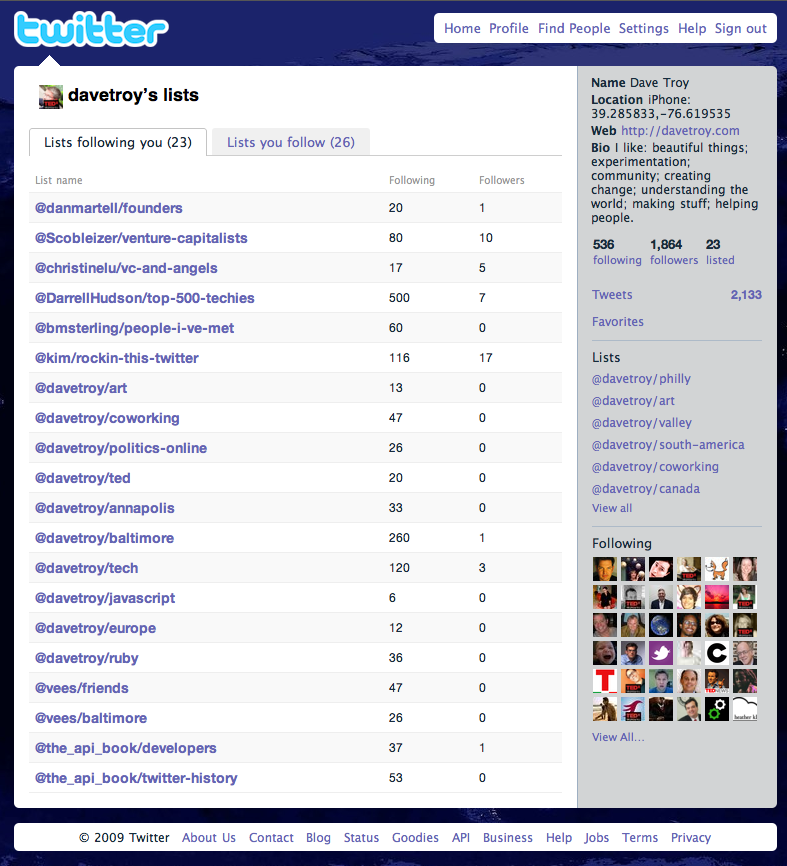

However, the new Twitter “Lists” feature has me thinking; this is an interesting feature not because of the “tech” but because of the implications on the developing economics of social networks.

First, what it is: Twitter “Lists” allows you to create lists of Twitter users that are stored within Twitter’s servers. You can name those lists (/twitter.com/davetroy/art) and those URL’s can either be public or private.

People can then follow those lists, which really is more like “bookmarking” them, as they do not appear in your Twitter stream. Those lists in turn keep track of how many “followers” they have, and you can see how many people “follow” the lists you create.

Traditional “Follower Economics” Are Dead

Jack Dorsey and Biz Stone always said that the best way to get real value out of Twitter was to follow a small number of people; it was never their intention for people to aim to follow more than 150-200 people (the “Dunbar number,” or people we can realistically expect to maintain relationships with).

With “Lists” you can add someone to a list, but not necessarily “follow” them. So, instead of “following” Ashton Kutcher, you can put him in a list that you call “actors,” or “attention whores.”

You can even put someone in a list (cool people), have them publicize that, and then change the name of that list to something less flattering (douchebags, or worse).

The issue of derogatory lists alone is one that Twitter will need to address.

So traditional “follower counts” are going to be meaningless – instead of “followers” people are going to start talking about “direct followers,” “indirect followers,” and “being listed.” It’s all changing, and I applaud Twitter for being willing to throw the old (flawed) assumptions about follower economics entirely out the window in favor of a new approach.

Buying Influence and Reputation

Within a few hours of the introduction of “Lists” I was put onto a few:

- @danmartell/founders

- @Scobleizer/venture-capitalists

- @christinelu/vc-and-angels

- @DarrellHudson/top-500-techies

- @kim/rockin-this-twitter

- @the_api_book/twitter_history

This early “seed” of my reputation is quite flattering and arguably pretty powerful (though a fraction of what I expect my ultimate “listings” will be). It shows that I am an “investor” and a “techie,” and considered so by some pretty influential people. I did nothing to influence this and would not consider doing so.

But, I am lucky and glad to have been so-described this early on. What if I really wanted to influence what lists I was on, or to appear on as many lists as possible? I can imagine now the jockeying to get onto the lists of all the “A-List” digitalistas will be intense and powerfully ugly.

Imagine the seedy things that might go on at tradeshows in exchange for getting “listed.”

Going forward, the primary question will be which specific lists you appear on (influence of curator, quality, scarcity) and, secondarily, how many lists you appear on (reach, influence).

“1M Followers” will be replaced by “listed by over 50,000,” or even “listed by the top 10 most influential people in microfinance.” And yes, listing counts will be a fraction of follower count, as lists will necessarily divvy up the people you follow through categorization.

Scarcity: You get 20 lists

It looks like people are allowed just twenty lists right now. That’s undoubtedly a scaling and design decision by Twitter to keep things manageable.

Putting aside for a moment all the reasons why people might want more than 20 lists, let’s accept the limitation. You get 20 lists. So it’s a scarce resource. It means Scoble, Kawasaki, Gladwell, Brogan, Alyssa Milano, Oprah, Biz, etc, all each get just 20 lists.

What will someone pay to get onto one of these lists?

Do you think that an author would pay to get onto twitter.com/oprah/incredible-writers? Yeah, I do too. Now imagine that, writ large, and scummier, with people even less reputable than Oprah. Now you see what I’m talking about.

At least buying followers is a scummy behavior that’s amortized over millions of targets; buying 1/20th of one particular follower’s blessing could lead to very high prices and extremely unsavory dealings.

The Coming “Curatorial Economy”

Twitter is doing this thing, and whatever Twitter does in house trumps anything that a third party developer might do, period. So, stuff like WeFollow, etc, your brother’s cool thing he’s making, Twitter directories: they are done, people. Or these external things must at least accept the reality of Lists and what they mean to the ecosystem.

Some folks have been complaining about the user interface for list management, etc, and that’s all moot: it will be available through the API, and you should expect list cloning, lists of lists, mobile client support, etc, pretty soon.

But the genie is out of the bottle. Start managing your reputation in a way that’s authentic and ethical and stay on top of this. And be prepared for what I’m calling the “curatorial economy.” (You heard it here first.)

Everybody’s making collections, and there are certainly people who will pay and be paid for listings. Count on it.