August 1st, 2010 — art, baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, software, trends

Putty Hill, a film by Matthew Porterfield (2010)

Something amazing is happening in the world of filmmaking. Crowdsourced funding mechanisms like Kickstarter.com are enabling a new generation of filmmakers to get a foothold doing what they love, where they want to do it. They’re using social media to find acting talent, and new digital camera technologies are making it possible to create amazing high quality films for a fraction of what it used to cost.

Matthew Porterfield

I’m particularly impressed by the work of Baltimore filmmaker Matthew Porterfield, whose films “Hamilton” (2006) and “Putty Hill” (2010) exemplify the new kind of “cinepreneurial” skillset which will certainly come to define 21st century filmmaking. (You can read here about the funding and creative process behind Putty Hill.)

Porterfield is a nice, unassuming guy who teaches film at Johns Hopkins and directs his students that if they want to make documentaries, they need to go to New York, and to go to Los Angeles for pretty much everything else. For today, this is sound advice. It’s the same kind of advice you’d give talented coders looking to unleash the next big web technology — go to San Francisco, because it’s where the industry is centered — at least right now.

But if you ask Porterfield why he doesn’t take his own advice, he’d likely offer a cryptic sort of answer — that he’d considered it but really couldn’t imagine himself anywhere else. I don’t know him well enough to speak for him, so I hope he weighs in here. But Matt and I are kindred spirits: we both are actively choosing place over anything else, and investing our time and talent to make it better.

Let’s Invest in Maryland Film, Not in Hollywood

Baltimore and Maryland have been the home to many well-known movie and television productions over the years, not the least of which have been Homicide: Life on the Street, The Wire, and a slew of Baltimore native Barry Levinson’s films including Diner, Tin Men, and Avalon. And most all of these productions received significant subsidies from the State of Maryland.

As budgets have continued to tighten, the O’Malley administration made a strategic decision to cut back on investment in film production subsidies. And that has probably been a very wise decision. Other states have been more than willing to outbid Maryland, offering ridiculous breaks. And Maryland really doesn’t need to be in yet another race to the bottom.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008)

The film The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) was based on a short story by F. Scott Fitzgerald (who lived around the corner from me in Bolton Hill when he wrote it), and it was originally set in Baltimore (original text). Yet the film version was set in New Orleans and had a subtext about a dying woman retelling the story as Katrina bore down on the city. Why? Subsidies. New Orleans offered more subsidies than Maryland would. And so the story was changed and moved there. Who knows if the Katrina storyline was a condition in the contract!

I don’t really have an opinion about whether Benjamin Button should have been filmed in Baltimore, but I do have an opinion about engaging in zero-sum games with 49 other desperate states: it’s bad policy. And I also think the time has come to admit that big movie studios are the next big dinosaur to face extinction. Why should Sony or Disney or Universal make the bulk of the world’s content when every man, woman, and child has access to a $200 HD camera and a $999 post-production studio?

Investing in Cinepreneurs

John Waters is one of Baltimore’s great artistic assets. And it’s not because of film subsidies. His work is known worldwide, and it celebrates the quirky, distinctive voice of Baltimore. Matthew Porterfield is distinctive and quirky too, and he makes beautiful pictures: he’ll be next to make his mark. And there are dozens more teeming around places like MICA, the Creative Alliance CAMM Cage, Johns Hopkins, Towson University, and UMBC. We need only to nurture their talent and the ecosystem.

Browncoats: Redemption, 2010

Another film, Browncoats: Redemption was made locally last year and created by local entrepreneurs Michael Dougherty and Steven Fisher. It is utilizing an innovative non-profit funding model. The film’s is raising money for five charities and it leveraged social media and Internet to recruit 160+ volunteers and market the film.

Instead of blowing money on Hollywood productions that bring little more than short term contract and catering work to Maryland, why don’t we instead start investing in the artists in our own backyard? Just as IT startups have gotten much cheaper to jumpstart, it’s now possible to make films for anywhere from $50 to $150K. If we dedicate between $5M and $7M to matching funds raised via mechanisms like Kickstarter, we could make something like 150 to 300 feature length films here in Baltimore. This would unleash a new wave of creativity that would yield fruit for decades to come, and put Maryland on the map as a destination for filmmakers.

We already have great supporters of film in the Maryland Film Festival, Creative Alliance, and many other organizations. It wouldn’t take much to get this off the ground. Instead of going backwards to the 1980’s in our view towards film production (as former Governor Ehrlich has recently proposed), let’s take advantage of all the available tools in our arsenal to jumpstart the film industry and move it forward in Maryland.

For every new artistic voice we nurture, we’ll be building Maryland’s unique brand in a way that no one else can compete with. It will make an impression for decades. And investing in film and the arts will help the technology scene flourish as well. Intelligent creative professionals want to be together. And coders and graphic artists think film and filmmakers are pretty cool.

We shouldn’t let an aversion to the failed subsidy policies of the past get in the way of forging a new creative future that we all can benefit from. We can invest in the arts intelligently. Let’s start today.

March 11th, 2009 — art, baltimore, business, design, social media, socialdevcamp, trends, visualization

On Monday, my wife and I went out for breakfast and she observed a bumper sticker on the back of an SUV. She said, “I just want to talk to these people and find out what makes people want to put these things on their cars.”

Those of you who know me well know that idle conversation runs a real risk of becoming reality; I tend to act on impulse to create things, especially if I can see a simple (enough) path to bring them to fruition.

Hence was born the idea behind Sticker Movie (working title), a documentary about the tribal meaning behind the stickers that people put on their cars. And so yesterday while working at the Hive, I tweeted that this would be a cool idea.

I immediately got back about 10 responses from people who liked the idea, and so I thought this idea might have some legs. Jared Goralnick (@technotheory) suggested that a project like this might be too much to take on (especially given everything else I am doing), and if I was interested in doing it all myself, he’d be right. But, I like to do what I’ve been calling marshaling the resources of the universe.

And Twitter is great at coaxing the universe into doing stuff. Efforts like @socialdevcamp, @bhivebmore, @baltimoreangels, @ignitedc are all things that wanted to happen and that I’ve helped catalyze in the last few months using Twitter — without having to do them all entirely by myself. And so it will be with @stickermovie — the first crowdsourced documentary.

We are going to start by getting submissions of bumper sticker images, so we can observe broad themes and develop a potential line of inquiry for the filming. Then we’ll use the power of networks to find an appropriate production team and any necessary funding. Finally, we’ll use networks to help drive the release of the film at festivals, and if it makes it that far, we will use social networks to drive the release theatrically.

So, big ambitions — no idea how it’ll work out, but I think the universe is on our side. It’s an interesting topic. Bumper stickers are a kind of modern tribal marker, and they tell us a lot about our culture and its own ambitions.

If you’re interested in following the @stickermovie story, go ahead and follow us on Twitter. We’ll be starting the sticker image collection shortly, and will keep folks apprised of our progress.

We hope @stickermovie will be another example of using Twitter to marshal the resources of the universe. Stay tuned. And start taking pictures of bumper stickers!

November 23rd, 2008 — art, design, software, trends

I was 5 years old in 1977, and all-in-all, I’d say the aesthetics of the day made a big impression on me. Here are some of the things that, looking back on it 31 years later, seem to share a common visual language and which were most influential on the next 10 years in movies, computing, games, and package design.

The rich colors and ground-breaking special effects of Spielberg’s 1977 Close Encounters of the Third Kind marked the beginning of a new era in filmmaking and ultimately set a goal for computer graphics and video games. The nascent digital graphics industry was barely capable of producing color “high-res” graphics, but folks knew that when they could, these were the kinds of graphic effects they wanted to make.

Maybe it’s just me, but it seems to me that Close Encounters, Atari, Space Invaders, and Star Wars were all linked together with a common visual sense. I think it’s pretty obvious that Atari ripped off Close Encounters for the Space Invaders packaging.

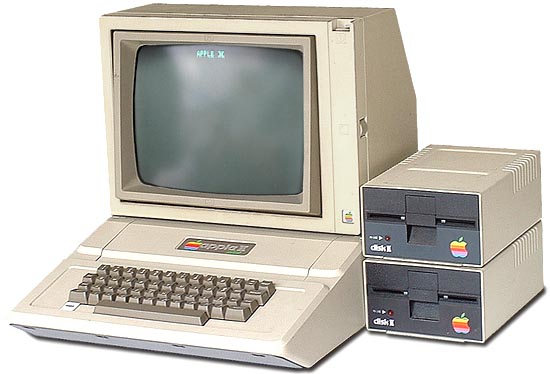

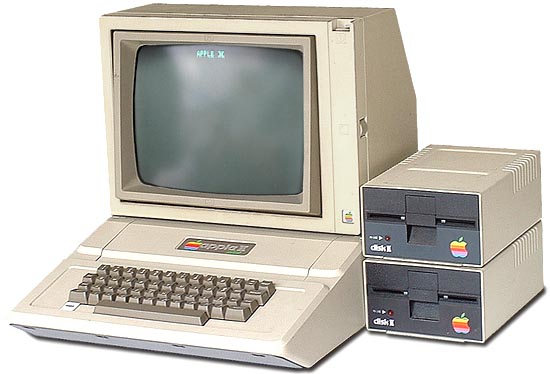

Likewise, the colorful “light organ” used to communicate with the aliens in Close Encounters is a close cousin, visually, to the famous Atari game Breakout. Steve Jobs was one of the designers of the arcade version of Breakout. Note the similarity to the original “rainbow” Apple logo.

Computer-generated music and sound was still in its very earliest stages, but the simple John Williams melody put to such brilliant use in Close Encounters was the sort of musical coda that aspiring game designers and programmers could latch onto and reproduce. John Williams of course scored hit after hit in movie soundtracks, but the Close Encounters and Star Wars themes of 1977 were hugely influential.

Spielberg used the Rockwell International logo (center) to clever aesthetic effect in Close Encounters; contractors at the secret military base at Devil’s Tower sported it, visually quoting the Devil’s Tower landscape. Of course, it’s interesting to note how similar the logos are for Atari, Rockwell, and Motorola – all major corporations of the day.

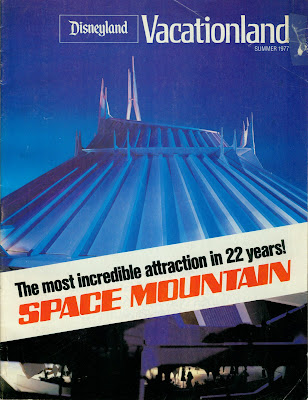

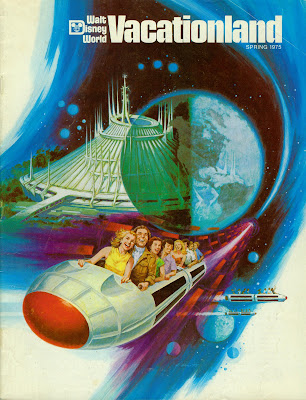

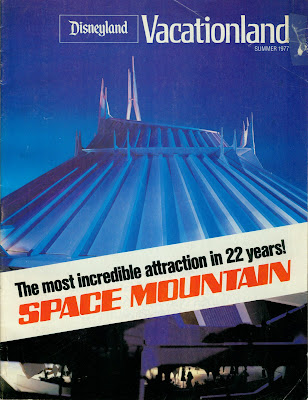

Disney got into the act in 1977 with the opening of Space Mountain. While they may not have been directly influenced by imagery from Close Encounters, Atari, or Star Wars, it’s clear that the popular imagination was drawing from common influences like Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey from 1969.

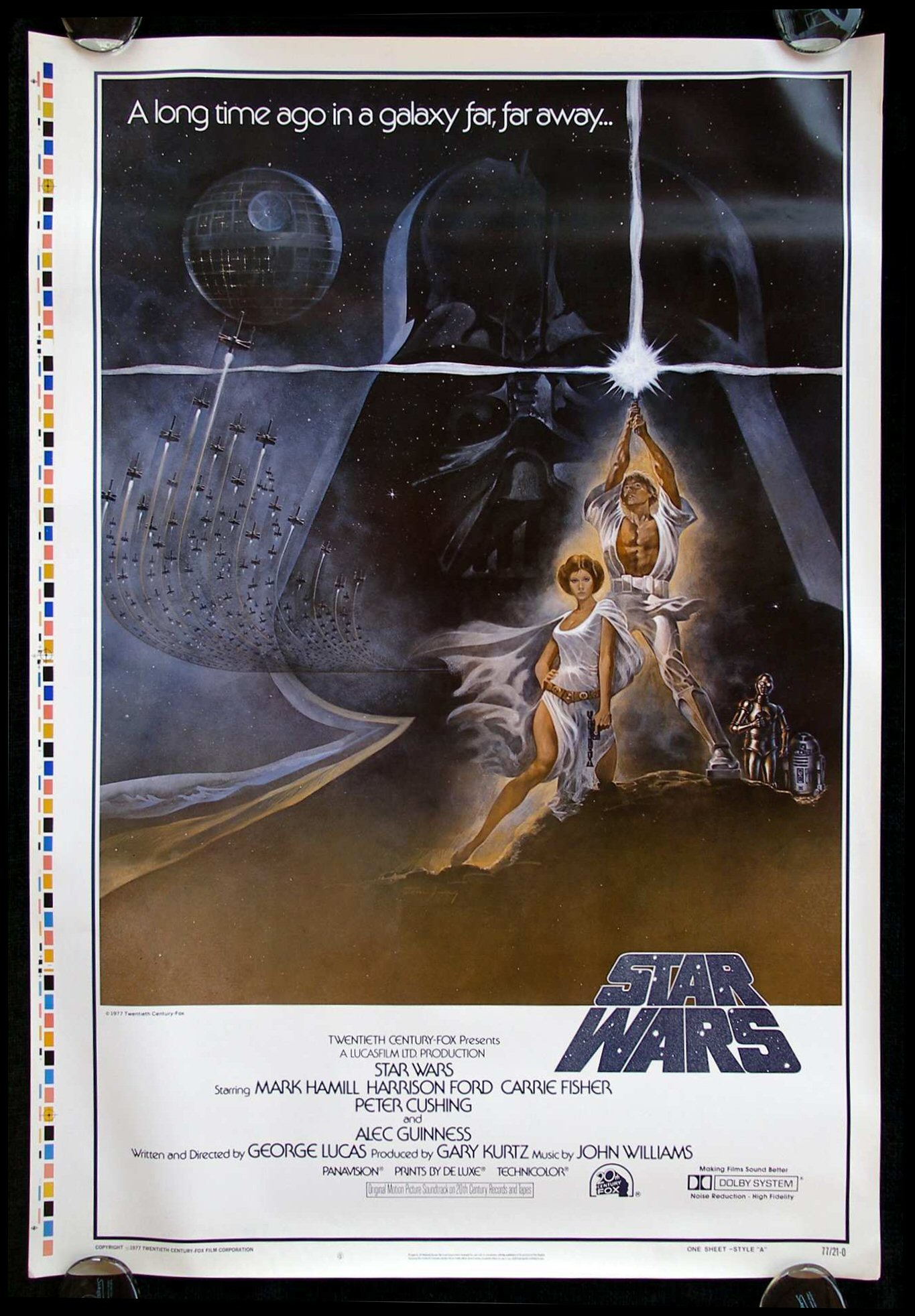

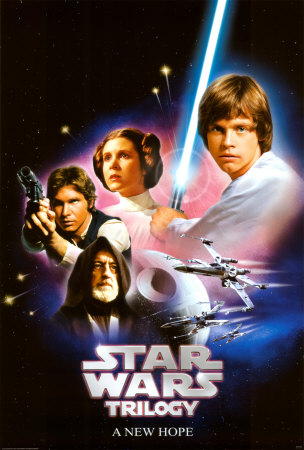

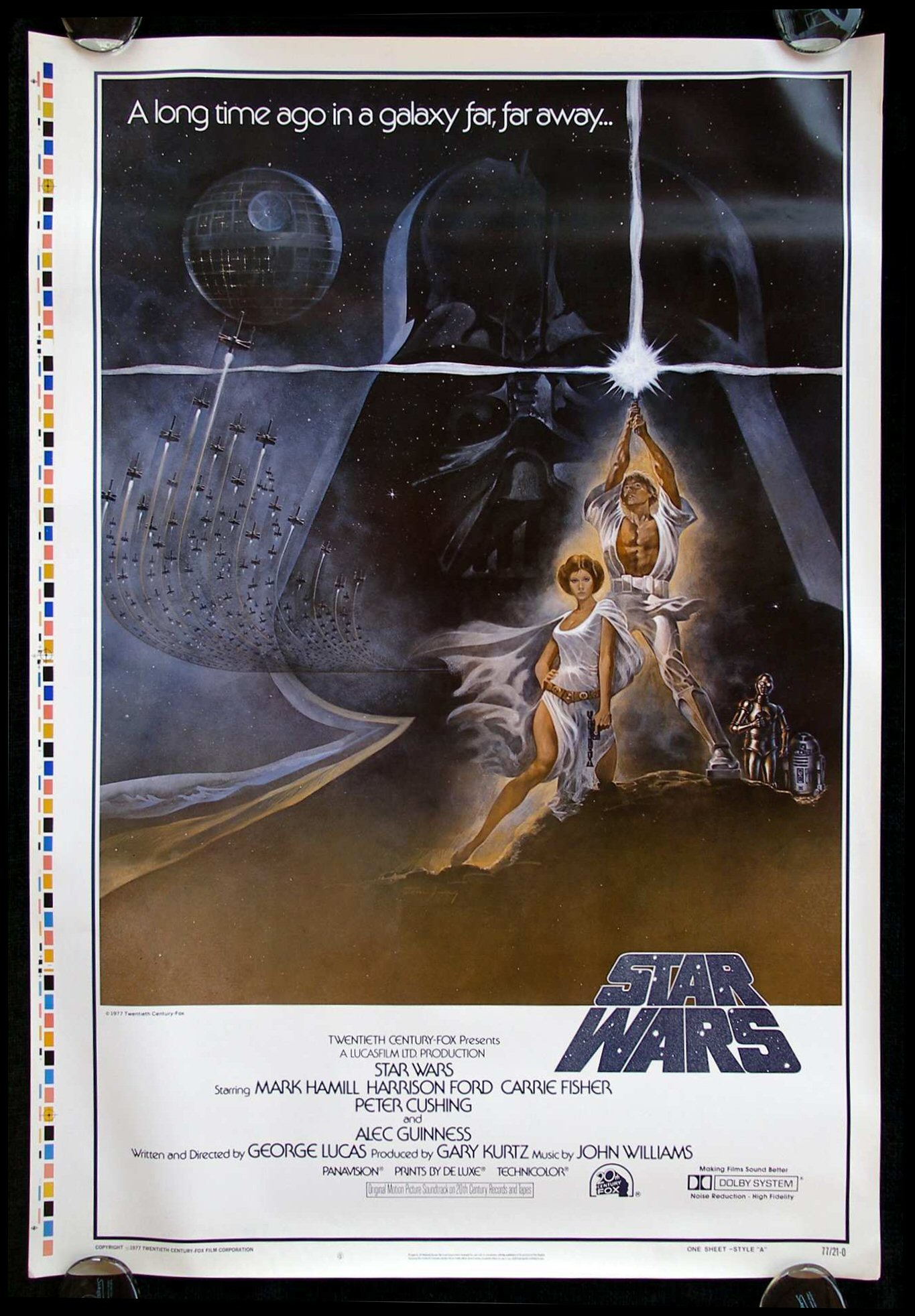

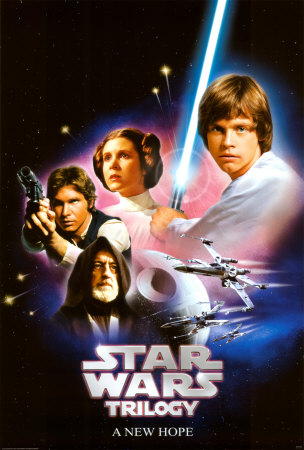

Of course the biggest influence of 1977 was George Lucas’ seminal work, Star Wars, which interestingly was not initially marketed using its iconic title graphics in its movie poster. It took a little while, and for the film to settle into its status as an international blockbuster, for it to adopt the visual marketing language that would become familiar in the release of the subsequent films in the series.

Arguably, the latter sans-serif Star Wars bubble letters were more inline with the iconography of Close Encounters, Atari, and the other major visual influencers of 1977. I’d bet the previous, blockier Star Wars graphic was designed in 1975 or 1976, before the film and its title graphics were completed. And the very earliest Star Wars art from the 1973-1974 timeframe used a hand-drawn serifed font — a different look altogether.

The dirty, realistic “used universe” designed for Star Wars was also influential. Unlike previous science fiction and space films, Lucas imparted his universe with a lived-in, beat-up look that added a romantic touch of decay to an imagined future — or past.

The Apple ][ was a direct result of Jobs’ (and Wozniak’s) work on Breakout, and the color graphics circuitry has much in common. And I don’t think it’s any stretch to say that the generation of Silicon Valley idealists that designed the Apple ][ and Atari 800 were hugely influenced by the blockbuster science fiction films of the day. While the early Apple designs lacked sufficient economy of scale or budget to have a very “designed” aesthetic, the Apple II does look like something straight out of the Star Wars universe. And the ugly Disk ][ and portable monitor are things that just didn’t get attention yet. Maybe they’re dirty, lived-in artifacts of a galaxy far, far away?

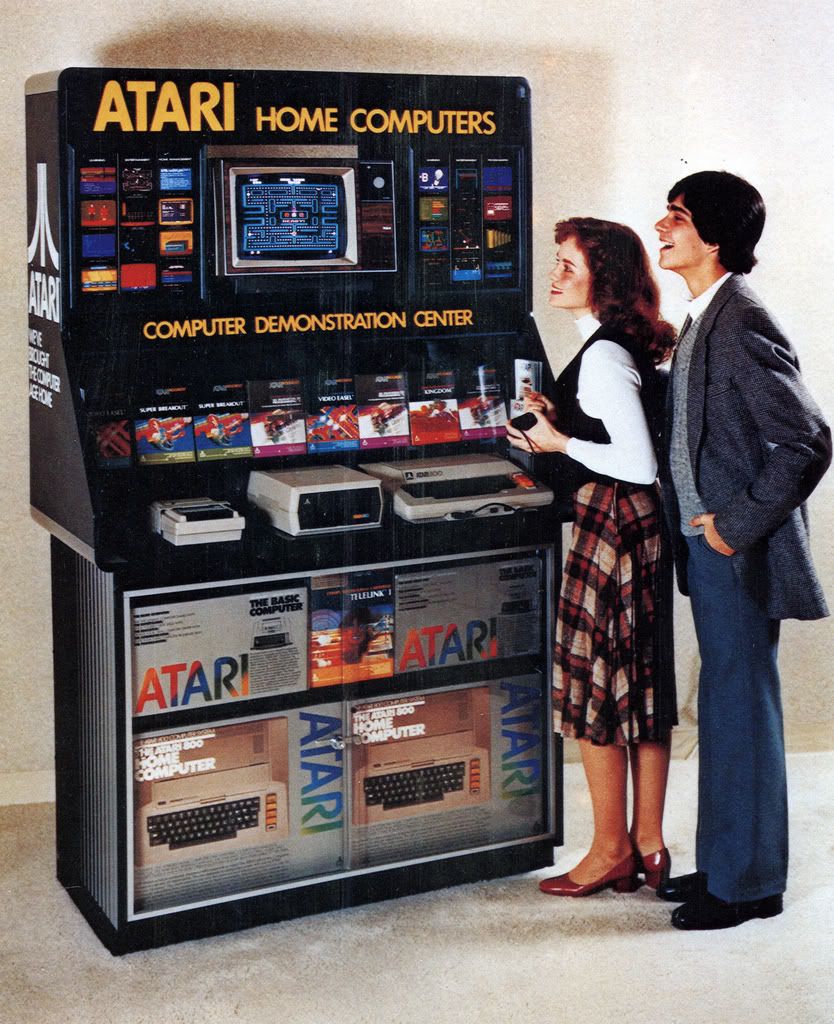

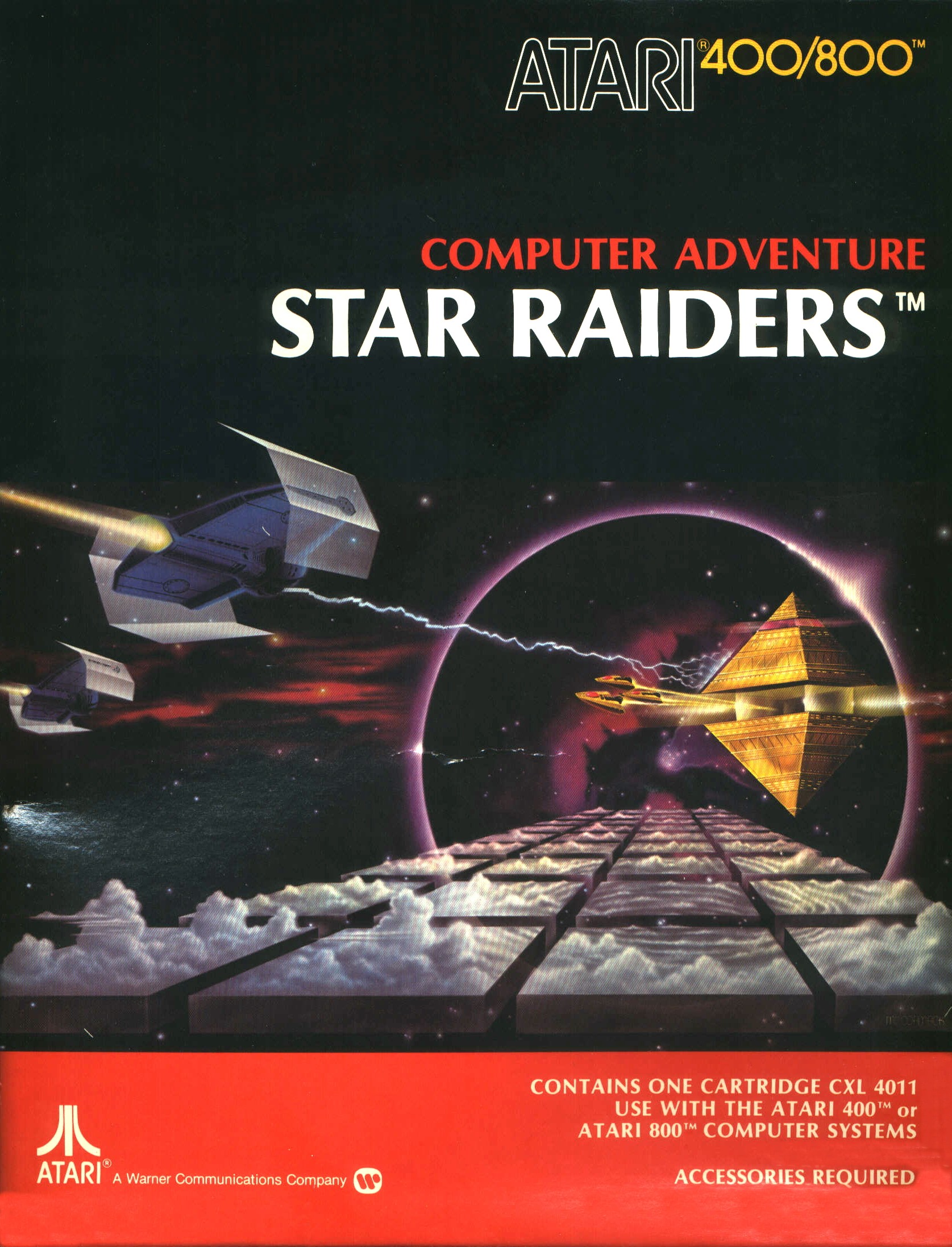

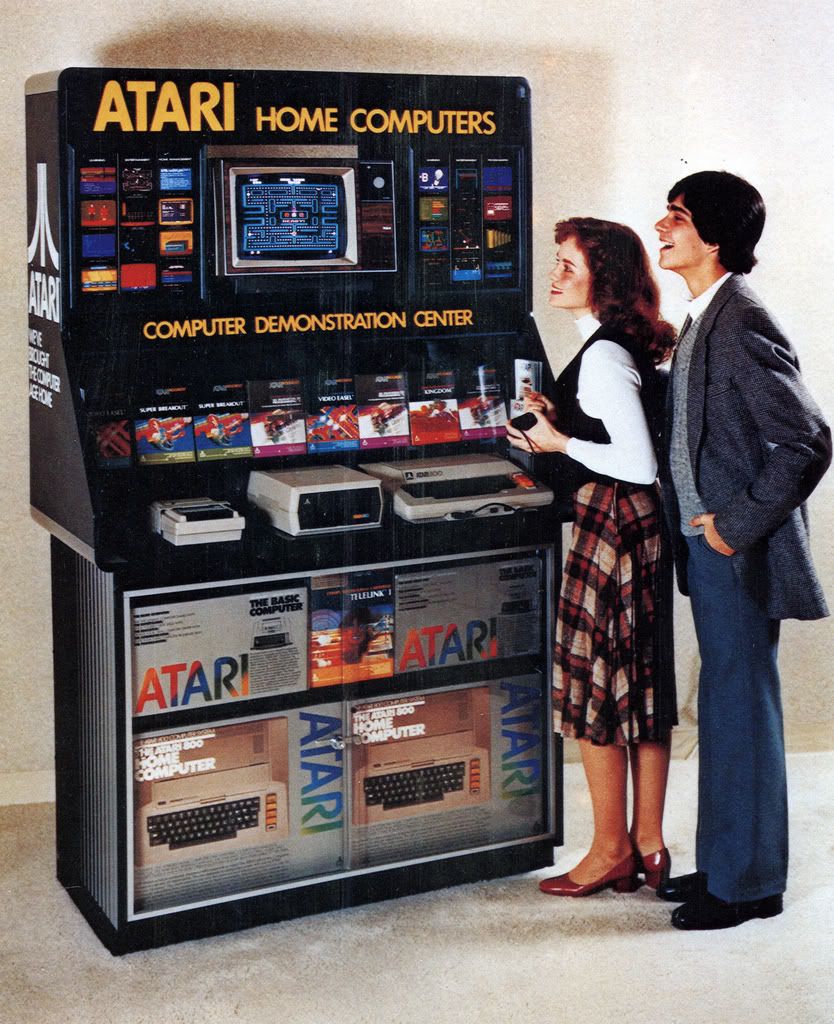

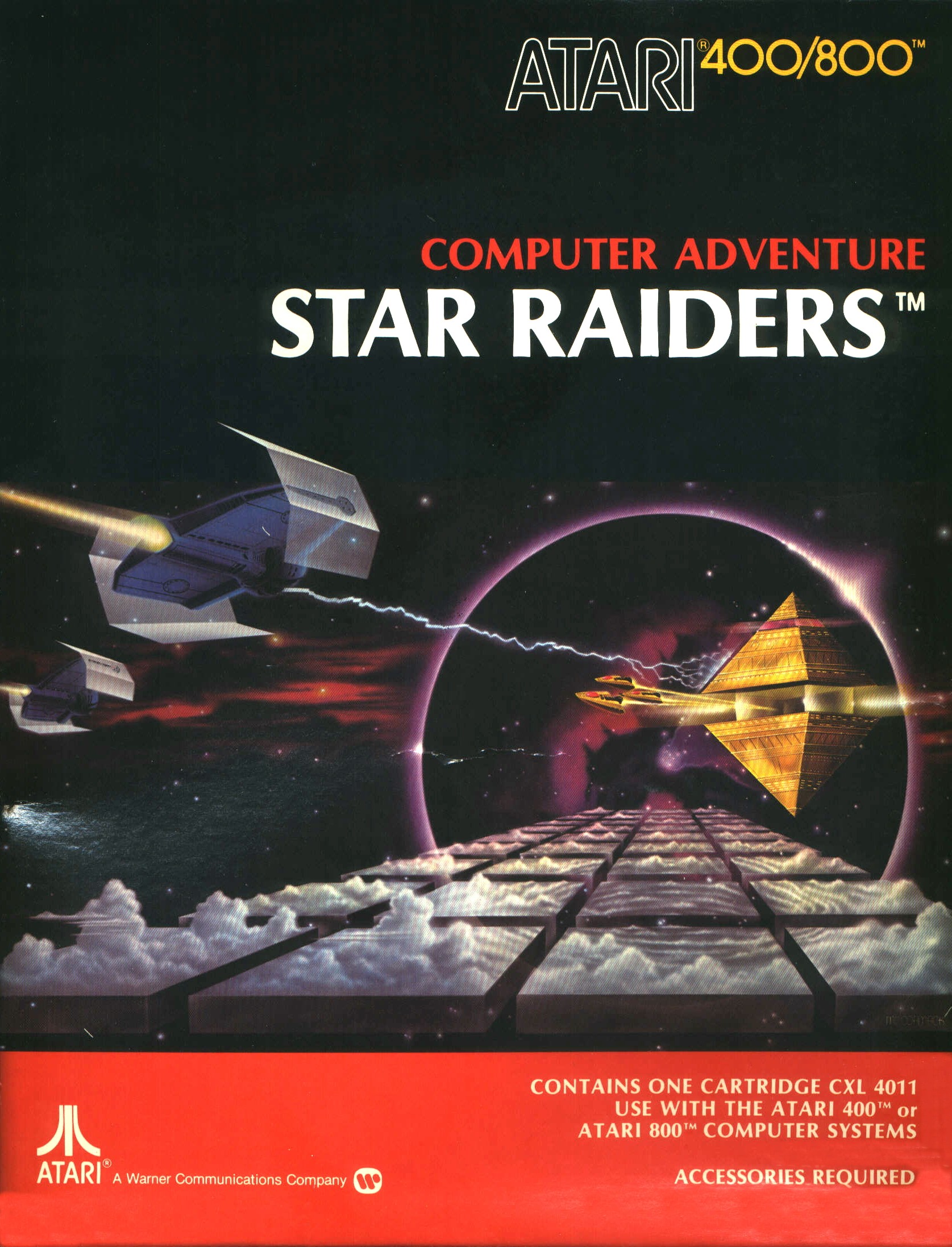

Atari, on the other hand, with the success of the 2600 VCS and its computers, had fully embraced the 1977 aesthetics and by 1980 had full color graphic packaging and a line of “Star Wars” compliant peripherals. And the packaging for the programs borrowed from movie poster designs.

Quite clearly Star Raiders (1979) borrowed directly from Star Wars. In fact, looking at this graphic, I’m now surprised that Atari didn’t get a phone call from Lucas. I guess this was back in the day before tie fighters were Tie FightersTM.

Media critics have argued that Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind marked the start of the era of blockbuster films, and a general shift in popular culture away from smaller, more thoughtful cinema and towards a populist, anti-intellectual approach in art and film in particular.

Whether that’s true or not, I think it is fair to say that 1977 did mark the year of a seismic shift in aesthetics that has been felt all the way through today in computing, gaming, film, and product packaging. Perhaps 1977 is a kind of bright-line marker for popular art — before and after seem to be from entirely different eras.

The fact that I’ve spent most of my life selling products or working in technologies directly influenced by this powerful aesthetic sense is likely no coincidence: to be young in 1977 was to be indelibly marked by the look and feel of a new era.