March 12th, 2011 — design, philosophy, politics, trends

Public education in America has long been the subject of hand-wringing and now, after over 100 years of the same model, it’s time we finally recognize what has worked and what has failed. Education is, in a sense, a kind of technology, and it’s time to ready its next version.

I’ve recently been asked to participate in some discussions about innovation in education; my mother co-founded a primary school in 1980 and I’ve had a chance to consider these topics as a student and a thinker. Here’s precisely where I believe we have failed and what we might do to invent the next generation of education.

Failure to recognize the importance of networks

What makes a successful student? Being around other successful students. We are the average of those around us. This simple fact is what has animated desegregation as well as programs like KIPP, Head Start, charter schools, Big Brothers/Big Sisters, and private schools. If we really want to create social mobility and social justice, we need to change people’s position within the social graph to expose them to self-actualized learners and educated people. This suggests one imperative only and it has nothing to do with schools, per se: If we want children to learn, we must ensure that they are surrounded by people who value learning.

Overconfidence in Curriculum, Testing, and the Educational Machine

If a child’s success is determined primarily by their position within the social fabric, it cannot also follow that the machinery of education has very much impact. Consider that a single child surrounded by a diverse, thoughtful, inquisitive support network of adults and other children will undoubtedly flourish (assuming a base level of socioeconomic security). It is therefore incorrect to assume that the modern educational machine is necessary to produce a successful adult. We should recognize that successful learning can happen in many different ways, and not just through schools.

Confusion about what “school” actually is

The popular conception of “school” is that it is a place where we send our children to learn and be systematically exposed to an orderly program of ideas, culminating in a baseline level of performance that will prepare them for employment. In fact, school provides only a) a basic social safety-net within which children can be placed into a social fabric, b) state-sponsored childcare, c) minimal insurance of the breadth of instruction (via a curriculum), d) minimal insurance of the length of instruction (usually at least 13 years of 180 days each). School enables some parents to participate in the workforce while insuring a basic safety net for students who would otherwise lack a supporting social fabric.

Confusion and guilt about the role of teachers

Many people intuitively understand the value of a good teacher. But look back on your own school experience and ask honestly how many truly excellent teachers you can recall. Most people will name three or four. Some might name five or six. This suggests that the best experiences in our educational system happen by accident. We all want to value teachers and the work that they do, but when performance varies so widely, it’s difficult to develop metrics that reward those who are making the most difference. Additionally, when others have demonstrated that self-directed learning is possible when children are working within a supportive social fabric, it’s not clear that the model of “teacher as the driver of learning” is sane. The child is the driver of learning, and the teacher is only an informed and enthusiastic member of the child’s social network. Children, not teachers, are the true drivers of learning; teachers are just one part of the child’s social support fabric.

Politicization of education

We have damaged both public education and social justice by conflating the two. Well-intentioned activists on the left identified public education as a civil rights issue. And certainly education is a matter of social justice. But education is a matter of one’s position within the social fabric, and we have been forced to try to use our public school system as the only available tool to manipulate peoples’ placement within it. Well-meaning bureaucrats and school boards make countless decisions that affect people’s placement within social networks – everything from what schools they can attend to what set of classes they can access. People on the right have mistaken left-wing proponents of public education as the enemy, when in fact the enemy is only the many layers of ineffectiveness that plague our system. We can only improve education when we understand the importance of social fabrics and stop fighting each other.

Historic co-opting of education alternatives by both the right and the left

Many on both the far right and left have historically chosen to opt out of public education in favor of religious education, private schools, home-schooling, or unschooling. Because they have been associated with extreme political affiliations, or with the moneyed (and oft-maligned) “elite,” many Americans have found them distasteful. Many intuitively believe that if they pull their child out of public education, they affect the social fabric of the schools they leave behind. However, many also fear that this alone is not a sufficient reason to participate in an underperforming school environment. You hear people say, “I believe in public education; that’s why I’ve got my kid in this school. I hope I’m doing the right thing.” People should put their children in schools only if they provide functional social networks for learning.

Over-reliance on causal thinking

We largely believe the myth that if you graduate as valedictorian and go to the best college that you’ll have a rich and successful life. That may appear true on the surface, but it’s arguable that more opportunities come from the social fabric that results from those experiences than from the credentials themselves. And even optimizing for “rich and successful” doesn’t necessarily translate to “happy and fulfilling.” We all know the old saw that “your degree doesn’t matter; what matters is that you have a degree.” That’s more true today than ever (at least outside of academia itself). The reason for this has more to do with our position within the social fabric than anything else. We need to start giving kids the skills they need to become life-long learners and stop trying to win some imagined game of education.

Vestigial artifacts

We educate children in an industrial model to prepare them to work in industrial environments, as if they were so many machine parts. We take off three months per year so kids can help with farm tasks. These are both obviously ridiculous notions today. So much of the system is the way it is because it has always been that way, and the system begets the system. We must break free. Learning should happen continuously and year-round, individually and in groups, and should be coupled with plenty of play and breaks.

How we might move forward

Buckminster Fuller famously said, “You never change things by fighting the existing model. Instead, make a new model that makes the old model obsolete.” This is happening right now.

First, new instructional tools are emerging. The phenomenal and free Khan Academy website provides deep instruction on hundreds of topics that kids can ingest at their own pace – and as supported by their network of peers and mentors.

Second, social tools like Facebook and Twitter enable people to self-organize face-to-face peer-driven instruction for their children. This will evolve into an effective, mainstream and apolitical home-schooling movement, and it will be a juggernaut.

People will opt out of public education because they will have found something that works better.

If we want to save the mission of public education, we urgently need to get smart about the nature of school, what it is and is not, and figure out a way to offer an effective social safety net for everyone that recognizes this new reality.

The old model simply doesn’t know it’s obsolete.

October 10th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, trends

When I was about four years old, my parents asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up. My response? A cashier. Why? They were the ones who got handed all the money.

Today, when people cite crime and education as the two major problems facing America’s cities, the knee-jerk response is to “protect city education budgets” and “put more cops on the street.” This is the same kind of simplistic logic I used as a child, and it’s just as wrong.

If this was how things worked, the safest cities in the world would be populated entirely by police, and the highest levels of education would be attained by those countries who spent the most on teachers and schools. This also is not true. Excluding repressive regimes, the areas with the least crime and most educated populations tend to be places where all citizens have access to the same opportunities.

Access to Opportunity

The new film by Davis Guggenheim, “Waiting for Superman,” chronicles a year or so in the life of a handful of students of different backgrounds as they struggle to get access to the educational resources they need to thrive. The heart-wrenching conclusion shows these kids – all but one – get denied that opportunity by a system that is clearly broken and unfair. 720 applicants, 15 spots. You get the picture.

If America is going to have a public school system, this kind of unfairness should not be tolerated. What happens to the kids that don’t get into the schools that can help them thrive? Should people have equal opportunity? Most people would say “yes.”

How We Got Here

Economic vitality is a kind of spotlight: it shines a light on things that need fixing, and provides the funds and political power to do so. Since our cities were torn apart by race riots and the global consolidation of manufacturing, the resulting precipitous decline in economic health has meant that cities have operated substantially in the dark. Watchdogs have been absent, and grassroots efforts have been underpowered.

American cities have reached a kind of feudal equilibrium. Politicians in power have little incentive to promote the kind of broad-based economic growth that could ultimately result in their ouster, but they can’t let things deteriorate so badly that everyone leaves – also stripping them of their power. And so American cities walk the line: with crime, schools, drug use and taxes locked at levels that are tolerable to just enough people that they are still worth milking, all while politicians hand out favors to power-brokers and childhood friends. Enough.

Ending the Abuse, from the Bottom Up

I wrote in my previous post that cities are now prime locations for idea-based industries. Over time this will mean an influx of wealth into cities as well as an increase in poorer populations in the suburbs.

Economic vitality in our cities borne from idea-based industries will result in a demand for accountable leadership and provide new levels of participation. In short, the feudalism will end when creative people begin to use their economic power to demand real change. The 40 year free ride is over.

Too many people in cities have resigned themselves to the idea that politics is a top-down enterprise — that it’s primarily influenced by the machine, by power-brokers, by community leaders, or by churches. Or that there’s a “turn based system,” where everyone who serves is given an equal shot unless they do something wrong.

That’s just wrong. American city politics from now on will be a bottom-up grassroots affair dictated not by the economics of writing checks to campaigns, but by the interdependent economics of jobs and a shared vision for the future of places that people care about.

Restoring Trust

To be workable, all power relationships must be a compact founded on shared values. Kids trust teachers that have their best interests at heart. Citizens trust cops who behave consistently and fairly. People trust politicians who put the civic interest ahead of their own.

There is nothing that ails us that cannot be fixed by restoring these trust relationships.

In “Superman,” Guggenheim asserts that bad teachers are kept around out of a “desire to maintain harmony amongst adults.” It’s difficult to stand up and fight to end someone’s teaching career, but it’s what’s required. To fail to do so is immoral.

It’s easier to keep getting a paycheck than to make enemies. And certainly there are dozens of systemic problems that make firing teachers very difficult. But that’s all that’s wrong with our schools, our police and our politicians: a simple failure to defend our core values.

And if we cannot agree on those core values – if a desire for personal gain exceeds a willingness or ability to serve the public – then those people deserve to be called out.

The Game Is Up

To be an old-school politician in a major American city today is to be in the way of a major cultural shift. Idealistic, intelligent, educated millennials armed with 21st century political weapons are coming, and they are going to ask why?

Why is the city so screwed up? Why are these jokers in power? Why are these incompetent teachers shuttled between schools? Why is more money spent on development deals for cronies than on parks? And why the hell can’t we clean up the blight that makes any trust or pride impossible?

Should we spend more money on schools or police? More than likely, all we need to do is let smart young people start asking questions. Crime and education take care of themselves if those that have violated the public trust can be removed from power. And with a little attention and common sense, we can ensure that more kids have a shot at the same opportunities.

Because in the end, crime, education, and blight are really just one problem, and it can be cured at least as quickly as it developed.

May 16th, 2010 — baltimore, business, design, economics, geography, philosophy, politics, trends

The American educational system deadens the soul and fuels suburban sprawl. It is designed as a linear progression, which means most people’s experience runs something like this:

- Proceed through grades K-12; which is mostly boring and a waste of time.

- Attend four years of college; optionally attend graduate/law/med school.

- Get a job; live in the city; party.

- Marry someone you met in college or at your job.

- Have a kid; promptly freak out about safety and schools.

- Move to a soulless place in the suburbs; send your kids to a shitty public school.

- Live a life of quiet desperation, commuting at least 45 minutes/day to a job you hate, in expectation of advancement.

- Retire; dispose of any remaining savings.

- Die — expensively.

Hate to put it so starkly, but this is what we’ve got going on, and it’s time we address it head-on.

This pattern, which if you are honest with yourself, you will recognize as entirely accurate, is a byproduct of the design of our educational system.

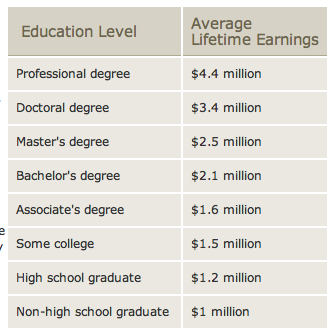

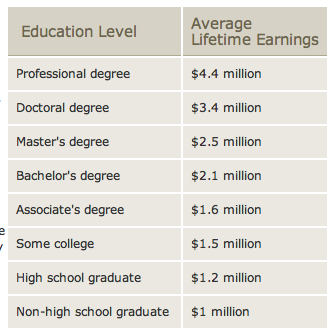

The unrelenting message is, “If you don’t go to college, you won’t be successful.” Sometimes this is offered as the empirical argument, “College graduates earn more.” Check out this bogus piece of propaganda:

But what if those earnings are not caused by being a college graduate, but are merely a symptom of being the sort of person (socioeconomically speaking) who went to college? People who come from successful socioeconomic backgrounds are simply more likely to earn more in life than those who do not.

There’s no doubt that everyone is different; not everyone is suited for the same kind of work — thankfully. But western society has perverted that simple beautiful fact — and the questions it prompts about college education — into “Not everyone is cut out for college,” as though college was the pinnacle of achievement, and everybody else has to work on Diesel engines or be a blacksmith. Because mechanics and artists are valuable too.

That line of thinking is the most cynical, evil load of horse-shit to ever fall out of our educational system. Real-life learning is not linear. It can be cyclical and progressive and it takes side-trips, U-turns, mistakes, and apprenticeships to experience everything our humanity offers us.

The notion that a college education is a safety net that people must have in order to avoid a life of destitution, that “it makes it more likely that you will always have a job” is also utterly cynical, and uses fear to scare people into not relying on themselves. Young people should be confident and self-reliant, not told that they will fail.

And for far too many students, college is actually spent doing work that should have been done in high school — remedial math and writing. So, the dire warnings about the need for college actually become self-fulfilling: Johnny and Daniqua truly can’t get a job if they can’t read and write and do math. See? You need college.

An Education Thought Experiment

I do not pretend to have “solutions” for all that ails our educational system. But as a design thinker, I do believe that if our current educational system produces the pattern of living I noted above, then a different educational system could produce very different patterns of living — ones which are more likely to lead to individual happiness and self-actualization.

If we had an educational system based on apprenticeship, then more people could learn skills and ideas from actual practitioners in the real world. If we gave educational credit to people who start businesses or non-profit organizations, and connected them to mentors who could help them make those businesses successful, then we would spread real-world knowledge about how to affect the world through entrepreneurship.

If more people were comfortable with entrepreneurship, then they would be more apt to find market opportunities, which can effect social change and generate wealth. If education was more about empowering people with ideas and best practices, instead of giving them the paper credentials needed to appear qualified for a particular job, it would celebrate sharing ideas, rather than minimizing the effort required to get the degree. (My least favorite question: “Will that be on the test?”)

Ideally, the whole idea of “the degree” should fade into the background. Self-actualized people are defined by their accomplishments. A degree should be nothing more than an indication that you have earned a certain number credits in a particular area of study.

If the educational system were to be re-made along these lines, the whole focus on “job” as the endgame would shift.

“A sturdy lad from New Hampshire or Vermont, who in turn tries all the professions, who teams it, farms it, peddles, keeps a school, preaches, edits a newspaper, goes to Congress, buys a township, and so forth, in successive years, and always, like a cat, falls on his feet, is worth a hundred of these city dolls. He walks abreast with his days, and feels no shame in not ‘studying a profession,’ for he does not postpone his life, but lives already. He has not one chance, but a hundred chances.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self Reliance, 1841

And so if the focus comes to be on living, as Emerson suggested it should be, and not simply on obtaining the job (on the back of the dubious credential of the degree), then the single family home in the suburb becomes unworkable, for the mortgage and the routine of the car commute go hand-in-hand with the job. They are isolating and brittle, and do not offer the self-actualized entrepreneur the opportunity to meet people, try new ideas, and affect the world around them.

The job holder becomes accustomed to the idea that the world is static and cannot be changed through their own action; their stance is reactive. The city is broken, therefore I will live in the suburbs. The property taxes in the suburbs are lower, so I will choose the less expensive option.

Entrepreneurial people believe the world is plastic and can be changed — creating wealth in the process. But our current system does not produce entrepreneurial people.

Break Out of What’s “Normal”

It may be a while before we can develop new educational systems that produce new kinds of life patterns.

But you can break out now. You’ve had that power all along. I’m not suggesting you drop out.

But I will say this: in my own case, I grew up in the suburbs, went to an expensive suburban private high-school — which I hated — where I got good grades and was voted most likely to succeed.

I started a retail computer store and mail order company in eleventh grade. I went to Johns Hopkins at 17, while still operating my retail business. Again, I did well in classes, but had to struggle to succeed. And no one in the entire Hopkins universe could make sense of my entrepreneurial aspirations. It was an aberration.

I dropped out of college as a sophomore, focused on my business, pivoted to become an Internet service provider in 1995, and managed to attend enough night liberal arts classes at Hopkins to graduate with a liberal arts degree in 1996. This shut my parents up and checked off a box.

I also learned a lot. About science. About math. About philosophy, literature, and art. And I cherish that knowledge to this day.

But I ask: why did it have to be so painful and waste so much of my time? Why was there no way to incorporate that kind of learning into my development as an entrepreneur? Why was there no way to combine classical learning with an entrepreneurial worldview?

Because university culture is not entrepreneurial. And I’m sorry, universities can talk about entrepreneurship and changing the world all they like, but it is incoherent to have a tenured professor teaching someone about entrepreneurship. Sorry, just doesn’t add up for me. Dress it up in a rabbit suit and make it part of any kind of MBA program you like; it’s a farce. Entrepreneurship education is experiential.

I had kids in my mid-twenties and now have moved from the suburbs to the city because it’s bike-able and time efficient. And I want to show my kids, now ten and twelve, that change is possible in cities. I believe deeply in the competitive advantage our cities provide, and I intend, with your help, to make Baltimore a shining example of that advantage.

I don’t suggest that I did everything right or recommend you do the same things. But I did choose to break out of the pattern. And you can too.

Maybe if enough people do, we can build the new educational approaches that we most certainly need in the 21st century. This world requires that we unlock all available genius.

March 5th, 2010 — design, economics, philosophy, politics, trends

I recently wrote an essay about how our educational system is an artifact of the industrial revolution, designed to produce cogs for a machine that no longer exists.

It received wide circulation and a lot of people weighed in with their own ideas about what’s working in education. My mother started a school when I was young, and I’ve also been in the process in the last year of evaluating school choices for my kids (who are entering middle school) so I’ve had a good deal more recent first-hand exposure to the question. And it’s got me thinking.

Play and Exploration

People learn by interacting with the world around them and by following the ideas they are curious about. Think back on your school career and try to name three teachers or three projects that really inspired you and got you excited. You can probably do that, but if I asked you to name four or more, you’d probably be at a loss.

Real learning doesn’t occur through mindless rote tasks or in any context where one is teaching to a test, and it almost certainly can’t occur in huge classes.

Kids grow when they are inspired to inquire into a subject themselves; sometimes that happens by way of a teacher, parent, or role-model, and sometimes it happens through reading or another kind of exposure to an idea. I won’t claim it’s causal, but there is a correlation between the number of books in a home and later success in life. While it is equally probable that the kinds of families that value books are also the same homes most likely to properly nurture a child, there is something wonderful about being surrounded by books and being able to select just the right book at just the right time.

Learning, at its best, should be a kind of just-in-time delivery system for knowledge and discovery.

There has been some debate as to whether schools should make any pretense of having a curriculum at all, or just focus on a kind of resource-rich play. The New York Times recently wrote a piece about how play is at the center of learning. A friend told me about the Sudbury School which has no curriculum and lets kids make up the rules. And if you read the literature, Sudbury “graduates” are as successful as anyone else.

Learning In Spite of the System

If you study the evidence, it becomes clear that the only real learning that happens in our traditional school environment happens by accident — as a side effect of our system, not as a primary result of our system. If this is true, our system is mostly wasted energy – noise and light – and not actually designed to solve the problem it purports to solve.

What do I mean by “learning by accident?” If you can count on one hand the number of teachers you had that inspired you, then your learning was by accident. If you can remember maybe just two projects from your school years that meant something to you, you were learning by accident.

The tragedy is that in our worst schools, those accidents never occur. Students slog zombie-like day after day through halls that threaten their safety, misdirect their higher calling into self-defense and trivial pursuits of one-upmanship, and generally burn them out on life and its possibilities. It’s no wonder that the survivors of this system (it’s hard to use the word “graduates” when many do not, and the process is more a trial than a system) tend towards cynicism and a zero-sum view of the world. There is no time or place for higher thinking when safety is in question.

Our very best schools – the schools in higher income areas, or our private schools – simply are rigged to increase the odds of “good accidents” occurring at a higher rate. These schools typically do not fundamentally alter the design, though, they just increase the odds that something good might happen inside their walls — through parent involvement, better teachers, and a community that is generally more able to support a learning environment.

So even our best schools are only, perhaps, 30% as efficient as they could be. The rest is all noise and heat and light. How can we unleash that untapped 70% of energy that we lose to the inefficient design we currently call school?

Homeschooling or the Sudbury method offer potential answers. However many alternative approaches carry baggage from the culture wars that make them unpalatable to the population at large, or include biases that make them less than effective.

Ideology and Indoctrination

Thanks to Hitler, it is still today illegal to home-school children in Germany. Indoctrination was such an important part of his new totalitarian state that he dared not leave it to chance. We have something similar going on in our country today. Our school system is a kind of indoctrination. We need to ask serious questions about whether we believe in the values it imparts, or whether it is something more sinister.

The extreme left and right get it wrong. This is not about warmed over hippie ideology, and it’s not about right-wing religious nuts opting out to preserve a cult-like bubble around their children. It’s also not about non-religious right-wing people rebelling against the abuses of teacher unions or big government. Education is too often co-opted by these sects and it’s counterproductive.

The real challenge is how to design an approach — which may not look at all like public education as we know it now, so stop reflexively bashing it — that scales up and works for moderates. And by “works” I mean delivers an level of efficiency closer to 90% rather than 30%, and is divorced from ideology.

Design is an opportunity to incorporate, or not to incorporate, ideology. Would you design a right-wing fork? Or a liberal toaster? Is it possible for us to design an educational approach that is simply functional, and light on ideology? We owe it to our kids to do so.